Denktank Nederland 2040 interview | Rob de Wijk: ‘Ik vraag me nooit af hoe Nederland er in 2040 uitziet’

Kom bij denktanklid Rob de Wijk niet aan met wensdenken. Verleidelijk wuivende toekomstbeelden zonder onderbouwing? Niet aan hem besteed. De hoogleraar internationale betrekkingen en oprichter van het The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS) zou je het realistisch geweten van Denktank Nederland 2040 kunnen noemen. Of, in zijn eigen woorden: ‘Ik ben de mopperpot van deze club.’

De eerste reden voor Nederland om in beweging te komen is geopolitiek, staat in het boek van de denktank. Dit is jouw expertise.

‘Nederland moet in beweging komen, ja. Het concept van een land is ooit in de zeventiende eeuw ontstaan met maar één doel: veiligheid. Aan die veiligheid hebben we jarenlang te weinig gedaan. Er is ondergeïnvesteerd in defensie. Er dreigen grondstoffentekorten, klimaatconflicten en handelsoorlogen. Daarin zijn we nu veel te kwetsbaar. Daarom is de noodzaak om te werken aan de positie van Nederland in de wereld redelijk strak doorgeredeneerd in het boek. We schetsen een wenkend perspectief voor een groener, menselijker en krachtiger Nederland, maar wel gebaseerd op de realiteit, op rapporten.’

We moeten investeren in defensie, zeg je. Maar je kunt niet heel veel geld uitgeven aan defensie, de energietransitie én sociale zekerheid tegelijkertijd. Dus hoe haalbaar is dat wenkende perspectief?

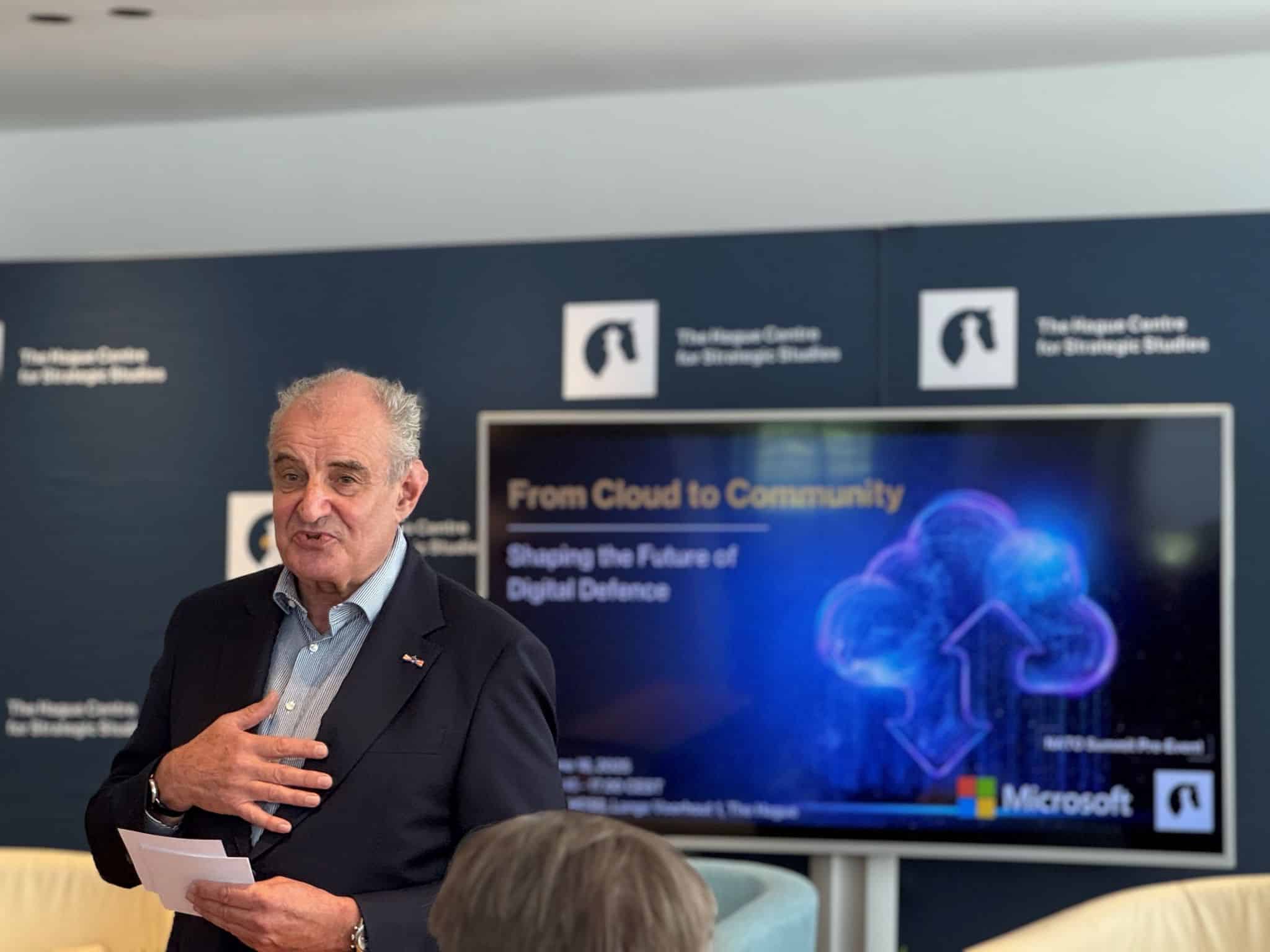

‘We moeten keuzes maken. En dat begint bij mensen niks op de mouw te spelden. Eerlijk zijn. Bijvoorbeeld over het feit dat wij in Nederland heel veel geld voor sociale zekerheid hebben kunnen uitgeven, omdat we konden schuilen onder de Amerikaanse defensieparaplu. Al in de jaren zestig zeiden de Amerikanen: wij kunnen niet betalen voor de ontwikkeling van jullie verzorgingsstaat. Die tijd is nu echt voorbij. Daarom gaan we 3,5 procent van het BBP aan defensie besteden om de achterstand weg te werken. Dat besluit wordt genomen tijdens de NAVO-top in Den Haag. Het geld moet ergens vandaag komen.’

Die boodschap heeft de massa nog niet bereikt.

‘Nee, zeker niet. Omdat politici het niet durven zeggen. Maar het percentage voor defensie wordt groter, dus het percentage van andere uitgaven wordt kleiner. Het is niet anders. Of je moet ernaar streven om enorm vaart te maken met de economische ontwikkeling van dit land. Maar daar lopen we ook tegen onze eigen grenzen aan. Net als bij de energietransitie. Dan denken we vooral na over wat we niet willen. We willen geen windmolens en niet nog meer kabels. Maar dat is decadent. Dan moet je niet gek opkijken als je over een aantal jaren met lege handen staat. Dat is de harde boodschap die niemand wil horen.’

Hoe zien die lege handen eruit?

‘De VS is al lang niet meer gefocust op Europa. Op het wereldtoneel gaat om de strijd tussen China en de Verenigde Staten.Je moet je daartoe verhouden als Europa en als Nederland. En dan is het antwoord vrij simpel: we moeten samenwerken. Maar daarin is Nederland nog erg lastig, hoor. Al hebben we door de geopolitieke veranderingen wel een cultuuromslag gemaakt. Daardoor gaan een aantal dingen makkelijker, zoals de samenwerking op defensiegebied. Trump heeft de herbewapening van Europa voor elkaar gekregen, wat je ook van zijn stijl vindt. En de discussie over de herstructurering van de economie in de Europa is op gang gekomen. Dat is ongekend.’

Hoe ziet Nederland er in 2040 uit, als het aan jou ligt?

‘Grappig genoeg stel ik me die vraag nooit, omdat ik weet dat het een niet te beantwoorden vraag is. Ik kijk naar de huidige ontwikkelingen en waar we dan logischerwijs uitkomen. De denktank beoogt in zeer belangrijke mate hoe wij vinden dat Nederland eruit zóu moeten zien in 2040: groener, socialer krachtiger. Daar heb ik natuurlijk absoluut geen bezwaren tegen. Maar het is mijn rol om dat niet te doen. Ik ben de mopperpot van deze club.’

‘Wensdenken is prima. Het geeft focus en energie aan het denkproces. Maar voor een visie moeten we ons ook baseren op feiten’

Moet je niet juist wensdenken en ambitieuze doelen stellen om in beweging te komen?

‘Wensdenken is prima. Het geeft focus en energie aan het denkproces. Maar voor een visie moeten we ons ook baseren op feiten. Die balans is in Nederland soms zoek, zoals in de energietransitie. Ambities, zoals volledig elektrisch rijden in 2035, zijn onrealistisch zonder voldoende infrastructuur en grondstoffen. We moeten realistisch zijn en kijken naar wat haalbaar is binnen de internationale context. Als de infastructuur achterblijft, kan je er vergif op innemen dat we in 2040 nog steeds fossiele auto’s verkopen. Dat zijn conclusies die mensen niet graag willen horen.’

Wat zijn de belangrijkste drempels voor een meer internationale aanpak in Nederland?

‘Er bestaat een enorme neiging om van binnen naar buiten te redeneren. We denken dat Nederland het centrum van de wereld is en dat alles maakbaar is. Terwijl we gewoon beperkt zijn in onze mogelijkheden door de internationale context. Alleen al voor onze handel zijn we enorm afhankelijk van andere landen. Inmiddels heeft Nederland zijn positie internationaal verspeeld, doordat onze politiek te gefragmenteerd is geworden. We worden gegijzeld door nationalisme en populisme. Daardoor is Nederland gewoon niet meer goed in staat om zich aan te passen aan de buitenwereld. En dat gaat ons welvaart kosten.’

Hoe kunnen we die buitenwereld binnenhalen?

‘We moeten meer denken vanuit de internationale context en stoppen met postzegels verzamelen. Een voorbeeld. In Nederland hebben we Natura 2000-gebieden die postzegels zijn en verweven zijn met agrarische gebieden. Wij zitten dan te puzzelen om de stikstofemissies precies daar te laten vallen waar we willen dat ze vallen. Wij denken dat alles maakbaar is. Maar Nederland is een klein land, dus denken we klein. Kijk naar Frankrijk. Daar wordt op een heel andere manier nagedacht. Zo’n groot land is niet zo maakbaar, en de politiek weet dat daar ook.’

Het gaat dus om een verandering van mindset?

‘Ja. Het gaat niet om de postzegel, maar om het hele album. Hoe verhoudt Nederland zich tot de rest van de wereld? En wat zijn dan de mogelijkheden om daarin te manoeuvreren? In Nederland vinden we dat de internationale context enorm beperkend is voor onze maakbaarheid en dus zeggen we: niet meer macht naar Europa. Maar klimaatverandering grijpt in Nederland hard in en schoffelt ons maakbaarheidsideaal onderuit. Daarom moeten we strategischer denken en anticiperen, zoals op verstoringen in de wereldhandel. We moeten ons realiseren dat Nederland sterk beïnvloed wordt door geopolitieke, economische en ecologische krachten. En we moeten flexibel zijn om te overleven in deze veranderende wereld.’

‘We moeten samenwerken met Europese partners en gelijkgestemde landen om onze positie te versterken’

Wat kunnen we concreet doen?

‘In ons boek hebben we geprobeerd om een aantal richtingen aan te geven en wat je ervoor moet doen om er te komen. We moeten samenwerken met Europese partners en gelijkgestemde landen om onze positie te versterken. En vraag je als land of bedrijf af: Waar komen de grondstoffen vandaan? Kan ik nog goed toegang tot mijn markt krijgen? Hoe zit het met mijn bevoorradingsketens en mijn afzetmarkt? Hoe gaan die veranderen? En hoe speel ik daar op in? Dit is Darwin, survival of the fittest. Wat mij aanspreekt in dit boek is dat wordt ingegaan op de ontwerpprincipes van beleid. Uitvoerbaarheid is nummer één, maar ook de samenhang met andere besluiten. Dat is goed en dit ontbreekt vaak in de politieke besluitvorming

Omdat er geopolitiek een andere wind is gaan waaien?

‘Die wind waait al heel lang. De geopolitieke verandering komt door de opkomst van China. In 2005 heb ik mijn eerste boek hierover geschreven. Toen zeiden ze: “Die Rob de Wijk is hartstikke gek, hij overdrijft”. Nu worden we met onze neus op de feiten gedrukt en zijn we al te laat. De situatie waarin we op dit ogenblik zitten met Rusland was niet gebeurd als we de boel bij defensie op orde hadden gehad. We hebben het huis dertig jaar lang niet onderhouden en nu lekt het dak aan alle kanten.’

Wat vraagt dat van de politiek?

‘Het blijft in de politiek veelal hangen in wensdenken. Plannen worden niet goed door doorgerekend en daardoor lopen dingen van de rails, of het nu gaat om de gaswinning, de toeslagenaffaire of de elektrificatie van het vervoer. Daarom is het belangrijk dat ons boek gelezen wordt. Het moet impact gaan hebben, zodat het geen papieren exercitie blijft, maar werkelijkheid wordt. Wat je zou willen is dat er een formele kabinetsreactie op komt.’