As the world’s 2nd largest producer of lithium, the exponential growth in demand for the metal has put Chile in a powerful position. On April 20th, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric announced his National Lithium Strategy (NLS), which many media proclaimed to be a nationalization of the lithium industry. But is the NLS really a nationalization? According to HCSS strategic advisor Jeff Amrish Ritoe, it is too early to refer to it as such: one needs to take a closer look at what was announced at the presentation before coming to any conclusions, he writes in this op-ed.

Chile’s National Lithium Strategy

Populist talk or genuine intentions to become the largest producer of lithium in the world?

On 20 April Chile’s President Gabriel Boric announced his National Lithium Strategy (which, for the purpose of this article will be referred to as ‘NLS’). According to Mr. Boric, the NLS is an attempt to generate and keep more wealth from Chile’s vast lithium reserves in the country. Chile is the world’s second largest producer of lithium and the exponential growth in demand for lithium to produce electric vehicles and portable consumer electronics like smartphones has put the country in a powerful position to set the terms and conditions under which it wants to engage with companies and countries who wish to secure access to lithium. Many mainstream media-outlets have framed the announcement of the NLS as a nationalization of the lithium industry in Chile leading to decreasing share prices of the two largest producers of lithium in the country, i.e. the American Albemarle Corporation and the Chilean based company Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile better known in the industry as SQM. Both companies are major lithium producers in the world and for both their Chilean operations are crucial to revenue generation.

Encyclopedia Britannica defines nationalization as ‘the alteration or assumption of control or ownership of private property by the state.’ One needs to take a closer look at what was announced at the presentation of the NLS on 20 April before coming to any conclusions.

But before breaking down the content of the NLS, some historic context on Chile’s lithium industry and regulation might be useful to see to what extent the country has been able to monetize its vast lithium reserves to date.

Cold War Hangover

Though Chile is typically viewed as one of the more business-friendly countries in South America, its lithium industry is strictly regulated. In 1979, military dictator Pinochet categorized lithium as a strategic resource due to its use in nuclear weapons, allowing the government to restrict lithium extraction.[1] Chile’s military regime decided that the sole right to explore for and produce lithium would be placed under a special regulatory regime that gave the Chilean state a monopoly to explore for and exploit lithium. Exploration and production concessions issued prior to 1979 were respected and remained intact but with the new regulatory regime of 1979 any private person or entity who wished to explore for and produce lithium was only allowed to do so by Presidential Decree which typically followed the advice of Chile’s Nuclear Energy Commission.

The five pillars of the NLS

The NLS is President Boric’s vision for extracting the full value from Chile’s vast lithium resources. The NLS rests on five pillars[2]:

1. The creation of a National Lithium Company. The plan is to create a National Lithium Company that will participate on behalf of the Chilean state in the entire lithium supply chain, from exploration to exploitation but also by participating in the production of batteries and battery components, through public-private partnerships (‘PPP’). During the second half of 2023, a bill is expected to be sent to Chile’s National Congress for the creation of the National Lithium Company.

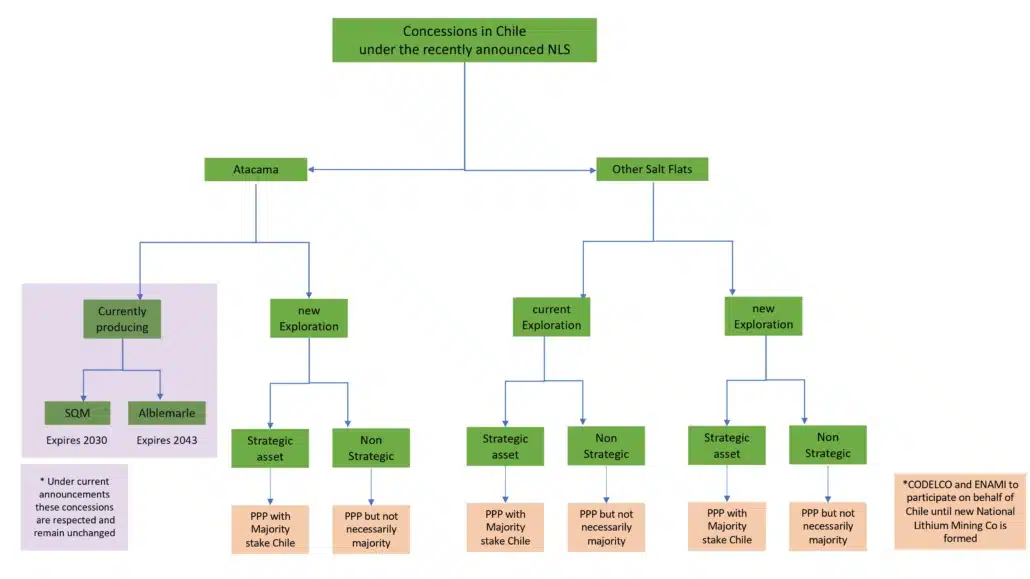

2. Public – private partnerships. Currently, there are 45 major salt flats in Chile. Two of these salt flats are production concessions in the Atacama, i.e. one held by SQM and the other held by Alblemarle. Mr. Boric has expressly announced that the current concessions for the production of lithium will be honored in all their terms. At the same time however Mr. Boric also announced that Codelco, the state mining company for copper, will soon initiate discussions with SQM and Alblemarle to discuss the terms of the extension of their respective concessions.[3] The starting position of the Chilean government will be to give the Chilean National Lithium Company a majority stake in these concessions once their current term expires.

In those salt flats where state entities like Codelco already hold a right to operate lithium projects, special exploration and exploitation lithium operation contracts (‘CEOL’) will be entered into between subsidiaries of these state entities and the Chilean state. This is already the case in salt flat Maricunga where Codelco holds a CEOL for activities.

Next to the Maricunga and Atacama salt flats, there are still 42 salt flats to develop, with 15 of them already in the exploration phase. This illustrates the daunting task for the Chilean government. Developing lithium projects requires money, expertise and experience in running lithium operations. If the ultimate target of the government is to maximize lithium production in Chile, the government will need to work with players from the private sector as Codelco and other state entities are not (yet) equipped to develop these projects alone.

Figure 1 depicts the PPP as currently envisaged under the NLS in more detail.

3. New technologies and research promotion. President Boric wants to minimize the environmental impact of lithium operations on salt flat ecosystems. To realize this goal the President wants to create a Public Research and Technological Institute for Lithium and Salars, a research & development institute tasked with offering new technologies to extract lithium in a more sustainable manner. Currently, the production of lithium requires large volumes of water and any improvement that can be made in the consumption of water or the emission of greenhouse gases for the generation of power required at the production facility could improve the environmental footprint of lithium operations in Chile.[4]

At the same time, President Boric has declared the creation of a network of protected salt flats and a salt flats zone in which no extractive operations will be allowed so that Chile can meet its commitments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Biodiversity.

4. Increased participation of local communities. The empowerment of local communities is part of Mr. Boric’s broader strategy to encourage stronger stakeholder participation in society and major industries through active involvement of indigenous communities, regional governments, academia and civil society. Specifically for the lithium industry, President Boric demands an increased participation and involvement of the communities living in the vicinity of mining sites.

5. Tax revenues. Under the NLS, the government wants to introduce a spending threshold for tax revenues generated from activities in the lithium supply chain. The idea behind a spending threshold is that part of the revenues can be saved to secure the long-term financing of crucial investments in Chilean society, promoting a sustainable and inclusive economic development over time.

Is the NLS a nationalization of Chile’s lithium industry?

The Chilean government needs partnerships with the private sector to accelerate the development of its large lithium resources but, at the same time, wants to keep control over the development and production of this 21st century white gold as much as it can. One has to keep in mind that the 1979 legal regime for lithium projects is still effective and therefore restricts the full exploration and exploitation potential of Chile’s vast lithium resources. President Boric’s announcement of the NLS needs to be placed in this context. The NLS recognizes that times have changed, and a regulatory restructuring is required to fully benefit from the increasing demand for lithium. Having said that, it is important to note that the NLS is not a policy nor regulation. It is a vision for how, at least in the view of leftwing populists, more wealth can be extracted from a rapidly growing industry for the benefit of the Chilean population in particular the indigenous people living in the vicinity of lithium projects. Nothing has been confiscated, no ownership has changed and no control has shifted. The NLS still needs to be worked out in detailed proposals before it can be presented to Chile’s National Congress which has the power to ratify it into law. But since President Boric does not have a majority in the National Congress has dramatically low approval ratings from the Chilean population, there is a real chance that the NLS will never see the light, at least not in its current form.

Coming back to Encyclopedia Britannica’s definition of nationalization then. As there has not been any alteration or assumption of control or ownership of private property by the state so far, it is too early to refer to the NLS as nationalization.

© Jeff Amrish Ritoe, HCSS Strategic Advisor

[1] See: https://verfassungsblog.de/lithium-and-constitutional-change/ 16 May 2023 and https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/chiles-national-lithium-strategy-new-beginning 28 April 2023 .

[2] See President’s Boric announcement of the National Lithium Strategy on 20 April 2023: https://www.gob.cl/litioporchile/en/

[3] On 26 May 2023 Codelco already opened the conversation on the terms of extension for SQM’s concession. Source: S&P Global, Commodity Insights “Metals Daily” 2 June 2023.

[4] There is a concerted effort from different stakeholders to drastically reduce the quantities of water needed to produce one ton of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE). See producers like SQM: https://www.sqmlithium.com/en/sqm-reducira-en-50-la-extraccion-del-salar-de-atacama/ and NGOs like Friends of the Earth: https://www.foeeurope.org/sites/default/files/publications/13_factsheet-lithium-gb.pdf

Image credit: European Space Agency, Salar de Atacama, Chile