Research

2017 is not over yet, but the year was ridden with alarming push notifications buzzing on our mobile phones. Political events are covered around the clock – from Trump’s Twitter antics to terrorist attacks sowing destruction around the world. In this constant barrage of news, it is easy to get caught up in today’s incidents, and lose sight of the risks that may transpire tomorrow. Earlier this year, HCSS published the Monthly Alert New Security Threats and Opportunities, the Other Side of the Security Coin on some of the more positive developments that are still occurring amidst all of the global gloom and doom that we get inundated with on a daily basis. In this November Monthly Alert, we turn our attention to the ‘dark’ side of the security coin and highlight ten emerging but security risks. For this Alert, we specifically looked for plausible but underappreciated security risks that may materialize in the foreseeable future and deserve attention now – also with an eye towards risk prevention and mitigation.

2017 is not over yet, but the year was ridden with alarming push notifications buzzing on our mobile phones. Political events are covered around the clock – from Trump’s Twitter antics to terrorist attacks sowing destruction around the world. In this constant barrage of news, it is easy to get caught up in today’s incidents, and lose sight of the risks that may transpire tomorrow. To counter this and provide a more forward looking perspective, the Strategic Monitor program continuously tracks the dynamics in the international security environment. It analyzes global trends and security risks with a time horizon of 0-10 years and gauges their relevance to European and Dutch national security.

Earlier this year, HCSS published the Monthly Alert New Security Threats and Opportunities, the Other Side of the Security Coin on some of the more positive developments that are still occurring amidst all of the global gloom and doom that we get inundated with on a daily basis.1 In this November Monthly Alert, we turn our attention to the ‘dark’ side of the security coin and highlight ten emerging but underappreciated security risks.

In parallel to this Alert, the Clingendael Institute (HCSS’ partner in the Strategic Monitor efforts) will release the Clingendael Radar later this month. The Radar features a comprehensive analysis of new threats and international cooperation based on a large survey of hundreds of security experts worldwide (see the textbox below).

| The Clingendael Radar What are the new dots on the security horizon? Clingendael conducted a large horizon scan in the fields of terrorism, migration, climate, Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear (CBRN)-weapons, and free trade to find out. The scan is based on a tried-and-tested method that combines various tools to detect new developments, such as a manual scan of available literature, a scan of recent and upcoming conferences from relevant organisations, and a scan of the important experts’ Twitter feeds. Crowd-based methods were used to validate these results and to reduce expert bias, among which the Clingendael Expert Survey: a questionnaire sent to over 2,000 experts worldwide. Below is a preview of the results that will be dealt with in a more comprehensive manner in a soon-to-be-published Clingendael report: 1. Terrorism-experts point towards the risks associated with the expansion of ISIS in South-East Asia, where the organisation could also relocate its stronghold. ISIS-aligned fighters are responsible for several terrorist attacks and kidnappings in the Philippines, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Indonesia, and are also expanding into Indian territory. The Strategic Monitor 2018 will have additional analysis on these five most important threats. |

While the Clingendael Radar examines security threats within five existing themes (terrorism, migration, climate, CBRN and free trade), the angle of this Alert – its focus on unappreciated security threats and their interconnectedness – ensures the complementarity of the two analyses.

For this Alert, we specifically looked for plausible but underappreciated security risks that may materialize in the foreseeable future and deserve attention now – also with an eye towards risk prevention and mitigation. In order to find underappreciated risks, the HCSS team started by reviewing more than 200 sources, including think tank reports, security foresight studies, blogs, newspaper articles and other publications published in the last year and identified the risks they contained. The team then also extracted the main security risks contained from a number of recent key Dutch or European strategy and policy documents and excluded those more widely acknowledged risks from the initial list (both lists are available upon request). The resulting list was subsequently scored by a team of HCSS analysts based on their overall impact, their specific relevance for the Netherlands, and the extent to which the analysts found these risks to be underappreciated. This analysis resulted in the ten security risks that are presented below with hyperlinks to articles that offer background information and a list of ‘interesting reads’ providing more context.

This Monthly Alert concludes with a few initial thoughts on what these underappreciated risks may tell us about the way in which we currently conduct defense and security foresight.

Ten Security Global Threats: Primat der Innenpolitik: Back with a Vengeance?

- Short Read 4 Factors Driving Anti-Establishment Sentiment in Europe — Nuclear Threat Initiative

- Short Read The Rise of the Trumps Amid a Crumbling Social Contract — Business Mirror

- Short Read From Brexit to European Renewal: the Fracture of the Social Contract Underlies the Current Turmoil — The London School of Economics and Political Science

- Short Read Anti-Establishment Politics is Far from Going Away — Bloomberg

- Long Read Populism: Between Renewal and Breakdown of Democracy — Clingendael Institute

- Long Read The Rise of Populist Sovereignism: What It Is, Where It Comes From and What It Means for International Security and Defense — The Hague Center for Strategic Studies

For the past few decades, our thinking on foreign and security policy has tended to focus on what was happening ‘abroad’, and what that meant for us ‘here’. Increasingly, the reverse is becoming at least as important: what is happening ‘at home’ is starting to affect the domestic legitimacy and feasibility of our foreign and security policies.

The last two years have seen lower levels of citizens’ trust in their governments; the unravelling of the ‘social contract’ between government and certain groups of citizens; the contested legitimacy of the political elites, institutions and the media; the rise of populist sovereignism (e.g. Brexit, Trump’s election); the increased popularity of far-right parties in Europe, etc.

The fragilization of the domestic social compact is starting to erode the very bedrock of our more ‘internationalist’ foreign and security policies. One indication of this is the decline of development aid across the developed world. In many countries – including the Netherlands – development aid is furthermore becoming more ‘interest-based’, focusing more on trade or migration reduction than on poverty alleviation, for instance.

Few analysts argue that Western efforts over the past few decades to improve international stability and prosperity through various ‘internationalist’ interventions have been optimally effective. But if the domestic sustainability of this more internationalist course becomes increasingly tenuous, this might lead to further deteriorations – even in those areas in which such efforts have been successful. A more inward-looking Europe could furthermore trigger various vicious security spirals in our immediate or more distant neighborhoods that could come back to haunt us.

Ten Global Security Threats: The Nuclear-Cyber Nexus

- Short Read Cyber Threats to Nuclear Weapons: Should We Worry? A Conversation with Dr. Andrew Futter — Nuclear Threat Initiative

- Short Read Growing Threat: Cyber and Nuclear Weapons Systems — Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Long Read The Dangers of Using Cyberattacks to Counter Nuclear Threats — Arms Control Association

- Long Read Cyber Warfare and Nuclear Weapons: Game Changing Consequences? — Clingendael Institute

- Long Read Cyber Threats, Nuclear Analogies? Divergent Trajectories in Adapting to New Dual-use Technologies — Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Listen Nuclear Strategy in the Cyber Age: New Challenges for the Ultimate Weapon — University of Birmingham

The alarming effectiveness of coordinated bit-based cyber-offensive operations in disrupting atom-based (physical) objects is receiving increasing policy attention. One related area that has received surprisingly little focused international debate is the connection between cyber threats and nuclear risks.

Recent security foresight reports have focused their attention on how our increased reliance on advanced cyber-technologies for the management and security of military and civilian nuclear infrastructures is creating heightened vulnerabilities. As offensive cyber-capabilities are becoming more sophisticated, the growing reliance on computers, codes and software in these nuclear facilities may lead to a Catch 22-like self-inflicted security dilemma, whereby attempts at making one’s nuclear assets more secure ends up creating loopholes that can be exploited by skillful hackers.

One of the security-related linkages between cyber and nuclear that comes up in this context is cyber-nuclear espionage, i.e. using cyber means to steal nuclear operational or design secrets. Especially Russia and the US are in the midst of expansive (and also extremely expensive) nuclear weapon modernization programs, in which cyber-elements – with all of their recently demonstrated vulnerabilities – play an increasingly important role.

A second issue that warrants more attention is how effective adversarial use of cyber capabilities could undermine the cornerstone of nuclear deterrence: all sides’ guaranteed second-strike capability. Cyber-offensives could lower the situational awareness of a potential target of an incoming first nuclear strike as well as the overall effectiveness of operational and/or strategic decision-making processes. The nuclear-cyber nexus could also raise additional problems for nuclear deterrence by undermining a number of other essential assumptions of deterrence theory related to the complexity and variety of potential attackers, the difficulty of attribution and its operation in a politico-legal grey area. One possible option here might be to explore new arms control initiatives, although even those would also be hindered by the attribution problem.

Ten Global Security Threats: War from Twitter

- Short Read Do social media threaten democracy? — The Economist

- Short Read Diplomacy in the Age of Social Media — The Wire

- Short Read Tech Giants, Once Seen as Saviors Are Now Viewed as Threats — The New York Times

- Long Read Twitter Foreign Policy and the Rise of Digital Diplomacy — Oxford Internet Institute

- Listen Can he tweet that? — The Washington Post

The politicization and ‘weaponization’ of social media as a channel are fraught with new security dangers. Examples include escalatory verbal cascades, miscalculations and misinterpretation, the danger of painting oneself in a corner, etc. The fact that tech companies’ responsibility in these dynamics remains murky does not help.

The realm of diplomatic interaction is changing beyond recognition. Traditional channels and practices of diplomacy are increasingly being supplemented by social media diplomacy; with more measured forms of communication by hyperbole and invective. This September saw the epitome of this trend as Twitter became instrumental in the war of words between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un. US President Trump took to Twitter to state his position and his sentiments; and within a matter of days, North Korea claimed that Trump’s tweet constituted ‘a clear declaration of war’. This particular dynamic now seems to have abated, but the world continues to follow Donald Trump’s twitter feed with baited breath. It is no longer inconceivable that tweets between thin-skinned leaders can spiral into knee-jerk, emotion-laden, uncontrolled decisions that may bring the world to the brink of war.

These developments are seen by many as a step back in the ongoing evolution of new forms of direct (but civilized) communication and interaction between politicians or policy-makers and a broader audience via social media. These darker forms of ‘disintermediation’, however, may bring more ‘Trump-like’ escalatory ‘surprises’ etc. – a fact of life that all stakeholders may have to get used to.

Ten Global Security Threats: Post-Putin Pandemonium

- Short Read Most Dictators Self Destruct. Why? — Bloomberg

- Short Read Imagining Post-Putin Russia — Global Security Review

- Short Read What Russia After Putin? — The New York Times

- Short Read Post-Putin: Imagining the Unimaginable — Vocal Europe

- Long Read Democracy by mistake — National Bureau of Economic Research\

On September 12, Vladimir Putin surpassed Leonid Brezhnev as the longest-serving Russian leader since Joseph Stalin. That event triggered a number of analysts to ponder what would happen if Putin were to disappear from the scene. Most of today’s Russia-analyses wrestle to come to grips with Putin’s Russia’s turn towards a more assertive international stance. The tenor of this particular recent set of ‘post-Putin’ ruminations is dramatically different from those analyses, but therefore not any less frightening.

The narrative of Russia’s current regime (often parroted in the West) is that Putin has restored a strong ‘vertical of power’ after a traumatic decade of poverty, instability and chaos. Most Western analysts, on the other hand, attribute Russia’s prima facie stability under Putin mainly to 14 years of skyrocketing oil prices, which have now come to an end. They furthermore claim that a pyramidal political system with a ‘strong’ leader on top unhampered by any real checks and balances is fundamentally brittle. This was painfully demonstrated when a very similar political system in Ukraine under previous president Yanukovich collapsed overnight as soon as he fled to Russia.

A recent paper by Daniel Treisman from UCLA examined 218 transitions from authoritarian regimes to democratic ones between 1800 and 2015. It found that “in about two thirds, democratization occurred not because incumbent elites chose it but because, in trying to prevent it, they made mistakes that weakened their hold on power. Common mistakes include: calling elections or starting military conflicts, only to lose them; ignoring popular unrest and being overthrown; initiating limited reforms that get out of hand; and selecting a covert democrat as leader.”

If Putin were to make one of the mistakes so amply illustrated in Daniel Treisman’s dataset of previous authoritarian leaders, democracy may indeed be one of the possible outcomes. But given the dramatic fragilization of Russia’s social fabric under Putin’s reign, the absence of checks and balances, the continued endemic corruption, and much lower oil prices, various non-democratic scenarios are certainly at least as plausible. Given Russia’s size, political weight in Europe, centripetal forces, societal fragility, more ‘modern’ than ‘post-modern’ political culture, lack of economic competitiveness, and (last but not least) military (and especially also nuclear) status – these alternative, more chaotic outcomes may deserve more policy attention.

Ten Global Security Threats: Artificial Intelligence vs. World Order?

- Short Read How Artificial Intelligence Could Disrupt Alliances — Carnegie Europe

- Short Read Artificial Intelligence(AI) and Global Geopolitics — The Huffington Post

- Short Read The Policy Dimensions of Leading in AI — Center for New American Security

- Short Read Artificial Intelligence and the Military — RAND Corporation

- Long Read Artificial Intelligence and National Security — Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center

- Long Read Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Defense — The Hague Center for Strategic Studies

- Watch Artificial Intelligence and Global Security Summit — Center for New American Security

AI-powered technologies are already changing the world and their presence is likely to continue to explode given the speed at which progress is being made in this field. Much is being written, also by HCSS, on the link between AI and defense/security. Some experts warn that the international consequences of the advent of AI could rival or even surpass in scale the revolutionary strategic impact that the development of nuclear weapons had in the last century. One of the areas in which the impact of AI remains virtually unexplored is the field of international relations.

Tomáš Valášek, the director of Carnegie Europe, recently fired the opening shot of what might become an interesting debate on this topic. He argued that AI “could soon make it easier for adversaries to divide and dishearten alliances” if it could succeed in undermining trust between allies by discrediting intelligence, faking high-quality spoofs of audio and video or penetrating the coding and the networks to probe for weaknesses in alliances. Diverging decisions by different allies to introduce autonomous weapon systems into their armed forces are also likely to lead to tensions. This would be all the more the case if fully autonomous weapon systems were to be used in an ongoing combined military operation. More generally, if one state in the international system decides to eliminate humans from the decision-making loop to use lethal force, will other states see themselves forced to follow suit?

Observers have questioned whether AI might become the mark of 21st century Sino-Western strategic antagonism. China is, already today, applying AI for (domestic) security applications in ways that Western countries have so far mostly resisted. Is it conceivable that it – and/or any other technologically advanced non-status quo powers – might start applying some of these algorithms in foreign policy? And what if nations’ possible foreign algobots were to get embroiled in downwards cascades as was the case in the ‘flash crash’ in the stock market in 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 1,000 points in a few minutes, wiping out about $1,000bn?

Ten Global Security Threats: De-Globalization and Isolation

- Long Read Predictions for 2017: globalisation takes a backseat — PricewaterhouseCoopers

- Long Read Measuring the health of the Liberal International Order — Rand Corporation

- Long Read Science Fiction Futures — United States Marine Corps

- Short Read The new world order, 2017 — The Washington Post

- Short Read Sci-Fi,’ dystopia, and hope in the age of Trump: A fiction roundtable — Wired

- Short Read The Twilight of the liberal world order — Brookings Institute

The world’s unprecedented second wave of globalization has been one of the foundational wellsprings of global developments over these past few decades. As the backlash against it is picking up steam in the form of the rise of populism, nationalism and sovereignism, the phenomenon itself shows signs of not only stalling, but even reversing itself. As we look ahead, accelerating trends like robotics, 3D manufacturing, local (and sustainable) energy generation, artificial intelligence and others may very well end up further eroding at least the ‘physical’ dimension of global interdependence. What will that mean for international relations?

Many analysts have highlighted the beneficial effects of the many interconnections of values and interests that were forged between nations during this second wave of globalization. These tremendously increased the (immediate and opportunity) cost of conflict and created and empowered influential global stakeholders – including private ones – to enforce stability and (also shared) prosperity. Maybe less noticeable – they also started replacing (more dangerous) mutually reinforcing ideational cleavages within and across nations with (more dampening) cross-cutting ones.

As nations may start becoming more self-sufficient in terms of manufacturing, energy dependence, food provision, etc. – what will this mean for these positive drivers of international concord? And how will this impact the softer, more ideational aspects of globalization: will people’s identities, values, etc. start diverging again instead of converging?

Ten Global Security Threats: Why Shoot if You Can Spin?

- Short Read Social Media and Democracy — The American Interest

- Short Read Facebook, Google and Twitter Could’ve Prevented the Russian Ads. Why Didn’t They? — Fortune

- Short Read In the fake news era, our need for experts has never been greater — Wired

- Long Read War by Other Means — Center for American Progress

- Long Read The Weaponization of Information: The Need for Cognitive Security — Rand Corporation

In an increasingly skeptical and unpredictable world, (dis)information campaigns and influence operations offer increasing promise to various state- and non-state actors to realize their objectives.

Using information as a weapon has a quantitative as well as a qualitative dimension. The exponential increase in the sheer quantity of data-altering information processing and dissemination in first instance leads to information overload. The qualitative manipulation of the masses via information flows furthermore undermines any trusted exchanges of information. These trends are likely to heavily impact societies and governments alike, and may even strike at the very heart of democracy and its values. With trust and freedom forming the basis of societal and political interactions, the reliability and accessibility of information is a sine qua non of a healthy democracy.

Recent technological advancements (e.g. digital avatars; real-time facial re-enactment, lip syncing, fake video tools) and new information transmission channels create new loopholes that open the doors to more and better cognitive manipulation. They often blur the line between reality and fantasy, making it difficult for the reader to distinguish ‘fake’ from ‘real’ news – a video of a Trump digital avatar, while still far from being perfect, shows the remarkable progress that has been made in this field with potential to have far reaching effects on people’s cognitive reference system.

Not only the technology but also the rise of tech companies’ influence in the information sphere is potentially a threat to general and specific biases. For example, Facebook and Google account for 40% of US digital traffic and content. Any mechanism that can be used for the spread of information possesses the power to alter societal perceptions. Consequently, this means that those who control these channels, be it through ownership, subversion (hacking) or regulation, wield a tool of immense political potency.

Ten Global Security Threats: Africa Adrift and Afloat

- Short Read Africa’s Future: seven key trends — Institute for Security Studies

- Long Read Why the Trump Administration Should Not Overlook Africa — Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Long Read Turning the tide — Clingendael Institute

- Short Read African development and security: shared opportunity, shared threat — Financial Times

- Long Read Security in Africa: A Critical Approach to Western Indicators of Threat — Center for Complex Operations

In comparison to the security threats emanating from the Middle East, Russia or China, those originating in Africa often seem to pale in intensity and urgency. However, a number of troublesome developments have significant security ramifications, not just for the continent itself but also for its immediate neighbour: Europe.

In the decades to come, Africa is predicted to face a toxic mix of security threats, with multiple possible spillovers onto the European continent. Firstly, terrorism is likely to continue to poison the socio-political dynamics of the African continent. Terrorist activity has been growing in Africa for some years, with attacks by groups such as Boko Haram, al-Shabab, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and ISIS accounting for an increase of 200% in the incidence and of 750% in the number of fatalities between 2009 and 2015. Given the near military defeat of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, chances are that the organization’s African fighters will return to the continent with both the ideological and operational wherewithal to inflame the terrorist threat.

Secondly, the population of Africa is projected to increase by roughly 50% by 2035, from 1.2 billion people to over 1.8 billion. In the absence of strong economic growth, this growth is likely to exacerbate the poverty-conflict trap. Thirdly, conflict and poverty give rise to net-outward migration, both within and outside the continent. Continued political instability is likely to further amplify current outflows.

Fourth, and finally, according to assessments such as the State Fragility Index, Africa exhibits a concentration of countries running a critical risk of becoming ‘highly fragile states’, among which large states such as Nigeria or Egypt, the failure of which could have significant implications for Africa, Europe and the world at large. Overall, those who ignore Africa, do so at their own peril.

Ten Global Security Threats: Terrifying Whac-a-Mole: The Evolution of Transnational Terrorism

- Long Read What does “nuclear terrorism” really mean? — The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists

- Long Read Facing the evolving Jihadi threat in Europe — Clingendael Institute

- Watch The Evolving Terrorist Threat — RAND Corporation

- Short Read The Jihadi Threat 2: Whither the Islamic State — Wilson Center

- Long Read After the Islamic State — The New Yorker

- Long Read Global Governance Monitor: Terrorism — Council on Foreign Relations

Whac-a-mole was a popular arcade game in the 1960s, in which players had to ‘whack’ a plastic mole with a small hammer, only to see a new mole appear from a different mole heap. The fight against global jihad shows a strong resemblance to this game. The imminent fall of the ISIS caliphate in the Levant is leading to the (re-)appearance of battled-hardened mujahideen in black holes of governance all over the world where they might be able to carve out a new territorial caliphate (as in the Philippines). It is also leading them to commit terrorist acts of different degrees of sophistication in the name of ISIS, including in Europe. That same pattern seems to be repeating itself now in Asia after the ‘liberation’ of Marawi, where the pro-ISIS leaders are already being lionized as martyr heroes. As a pro-ISIS posting warned, “Marawi is just the beginning” and “new cubs and soldiers” will be trained to fight the “crusader forces”. Myanmar or Central Africa are mentioned as possible candidates for new caliphates.

An area of particular concern is that jihadist groups, in their quest to sow terror in the hearts of ‘infidels’, might ultimately resort to the use of weapons of mass destruction. It is important to recognize that this threshold has in all likelihood already been crossed, as ISIS was confirmed by the OPCW to have used chemical weapons in Iraq and Syria. In the nuclear domain, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on 15 October 2014 concluded that the danger of ISIS acquiring nuclear weapons was real but small: “Let’s not exaggerate the threat.” They did note, however, that “the most likely threat is a radiological device of some kind.” A March 2016 IHS Markit (formerly Jane’s) analysis of this threat argued that ISIS has access to a number of sources that could potentially be used to manufacture a radiological dispersal device (RDD) or ‘dirty bomb’, which it called “a formidable although not insurmountable problem for the Islamic State”. Furthermore, recent activity on the dark web suggests terrorist groups are seeking to acquire the technologies necessary for developing WMDs.

Other risks include the exploitation of dual-use systems by terrorist groups and their ability to wage large-scale cyber-attacks. Altogether, these trends point towards transnational terrorism turning into a terrifying ‘Whac-a-Mole’.

Ten Global Security Threats: Internet of (Vulnerable) Everything

- Short Read The Internet of Things will be even more vulnerable to cyber attacks — Chatham House

- Short Read European Union to Social Media: regulate or be regulated — Center for Strategic & International Studies

- Short Read The end of net neutrality could shackle the internet of things — Wired

- Short Read The battle for the future of the internet is here — Information Age

- Short Read Alle apparaten straks online: zie dan maar eens een cyberramp te voorkomen — Volkskrant

- Listen Net Neutrality: The war is over — Brookings Cafeteria

The dramatic cost decreases of smart internet-connected devices (cars, locks, thermostats, toys, etc.) are starting to make the Internet of Things a reality in our everyday lives. US research and advisory firm Gartner estimates that 8.4 billion connected things are in use worldwide in 2017, a 31% increase over 2016. This suggests that we are now entering the ‘knee in the curve’ of an exponential acceleration in the roll-out of this technology. The security implications of this trend are nicely summarized in what is being called Hypponen’s law: “Whenever an appliance is described as being ‘smart’, it’s vulnerable”. One of the fundamental challenges here is that companies are more interested in making sure that they can get everything to work as cheaply as possible than they are in making sure that it will do so securely (throughout the lifecycle).

The security impact of this law is further accentuated by the expansion of the internet of things to what networking giant Cisco has labelled the ‘internet of everything’ – the intelligent connection of not only things, but also people, processes and data. This provides hackers with new opportunities to launch attacks of unprecedented scale and impact, as became visible in a recent wave of global ransomware attacks, that affected organizations around the world including the port of Rotterdam, the UK’s National Health Service, airports, etc.

Much is being done by various private and public actors (including by HCSS as the host of the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace) to address cyber-security and -stability, but it is clear that daunting challenges lie ahead.

Final Thoughts

The list presented here attempts to flag a number of plausible risks of potential relevance to the Netherlands that may not (yet) – based on the risks specified in a number of recent key Dutch and European security and policy documents – have received the policy attention they deserve. Do these risks share some characteristics that make them less likely to be included in more mainstream security risk overviews? Even though our list is far from exhaustive, it does allow us to suggest a number of intriguing parallels.

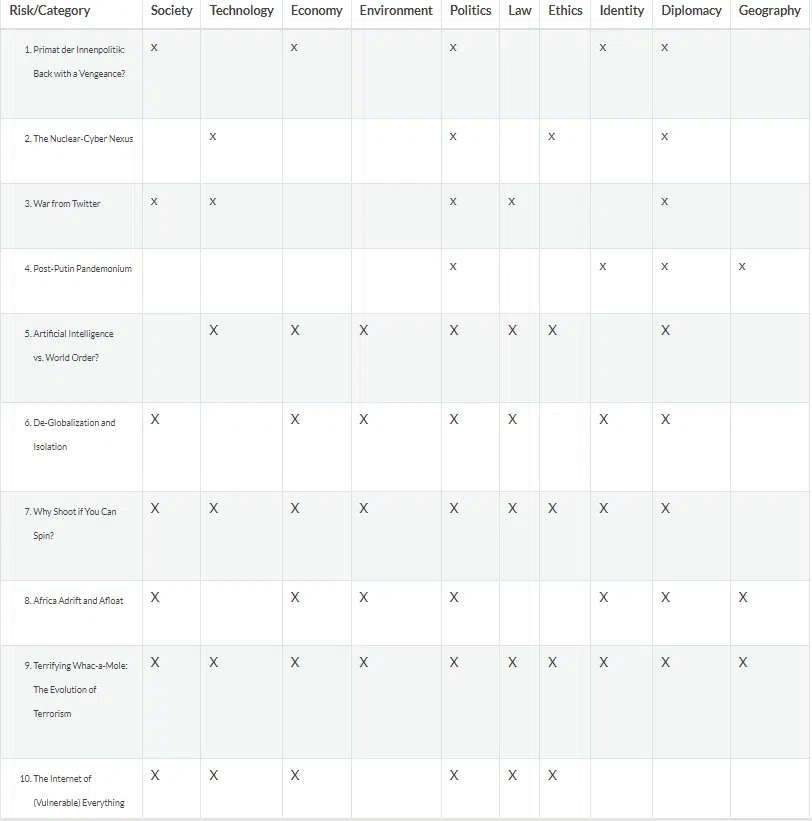

A first one is that much foresight work uses a number of established categorizations to identify risks or opportunities. These include various popular mnemonic acronyms like PEST, STEP, STEEP, STEEPLE, PESTLE, DIME, DISMEL, PMESSI, etc. Inevitably, using such rigid taxonomies implies that non-included categories run the risk of being ignored. The following table tabulates the 10 risks highlighted in this Monthly Alert against an expanded ‘taxonomy’ based on the widely used STEEPLE taxonomy, but augmented by a few categories that are not usually included, but that appear to have been gaining in importance – like diplomacy, identity or geography. The table shows that quite a few of the underappreciated risks we identified also belong in those less-frequently used categories. If a more systematic investigation of a wider set of foresight studies would support this initial hypothesis, this would suggest the need for a more cautious (and creative) approach to our use of such taxonomies.

A second common thread running throughout a number of these underappreciated risks is that they tend to be ‘compound ones’: they constitute developments in which acknowledged risks (such as nuclear and cyber, or AI affecting the world order) combine in potentially unexpected and dangerous ways. The same interestingly applies across risks and opportunities – e.g. social media is often seen as a force for good, but in the past year or so, the combination with populist leaders has revealed the flip-side of this coin with potentially dire consequences. The take-away from this potential fundamental foresight flaw is that more work should be done on exploring various combinations between acknowledged risks and opportunities.

To sum up, the early and pre-emptive identification of the entire risk-space – which is the scope and purpose of this Monthly Alert – is critical to our governments’ ability to handle and mitigate risks. Policymakers will increasingly have to come to grips with how this impacts the work of our defense, foreign and security policy institutions: the issues at hand, the increasing speed of developments, the way threats are perceived and conceptualized, and the way they conduct their work – including the use of social media and/or AI, etc.

Authors: Stephan de Spiegeleire, Karlijn Jans, Andreea Rujan, Kars de Bruijne, Minke Meijnders

Contributors: Tim Sweijs

About Monthly Alerts

In order to remain on top of the rapid changes ongoing in the international environment, the Strategic Monitor of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defense provides analysis of global trends and risks. The Monthly Alerts offer an integrated perspective on key challenges in the future security environment of the Netherlands along the following four the:

- Vital European and Dutch Security Interests

- New Security Threats and Opportunities

- Political Violence

- The Changing International Order

The Monthly Alerts reflect the monitoring framework of the Annual Strategic Monitor report, which is due for publication in January 2018. Each Monthly Alert offers a selection of discussions of emerging developments by key stakeholders in publications from governments, international institutions, think tanks, academic outlets and expert blogs, supported by previews of ongoing monitoring efforts of HCSS and Clingendael. The Monthly Alerts run on a four-month cycle alternating between the four themes.

Disclaimer

Monthly Alerts are part of the PROGRESS Program, Lot 5, commissioned by the Netherlands’ Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense. Responsibility for the contents and for the opinions expressed rests solely with the authors; publication does not necessarily constitute an endorsement by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs or Defense.

1. In our futures’ work, we always aim to strike a balance between what we have called the ‘two sides of the security coin’: the darker ‘conflict’-side in which agents of conflict use whatever means available to undermine international security; and the more upbeat ‘resilience’ side, in which the healthy fibers of a society positively leverage various developments in the world, thus strengthening its security ‘immune system’. For more background: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (2016) Si Vis Pacem, Para Utique Pacem. Individual Empowerment, Societal Resilience and the Armed Forces.