Research

How should the Dutch government prioritize partnerships with other nations? Which countries are strategically important? Which are compatible in terms of shared values? Traditionally, Dutch foreign policy has a dual orientation: the pursuit of Dutch interests on the one hand and the adherence to and promotion of norm-based values on the other. How to handle relationships in a increasingly connected and complex world? HCSS is developing a Dutch Foreign Relations Index (DFRI) as an analytical basis for a framework to provide guidance on this.

This Monthly Alert presents the findings of a high-level analysis of this first current iteration of the DFRI. It offers, from the Netherlands’ perspective, an overview of the utility and compatibility of states worldwide and the changes therein over time. Clusters of countries are derived based on a combination of these two dimensions. The alert concludes with suggestions as to how the DFRI could be further developed and leveraged as an analytical input into the partnership prioritization process in Dutch official foreign and security policy making.

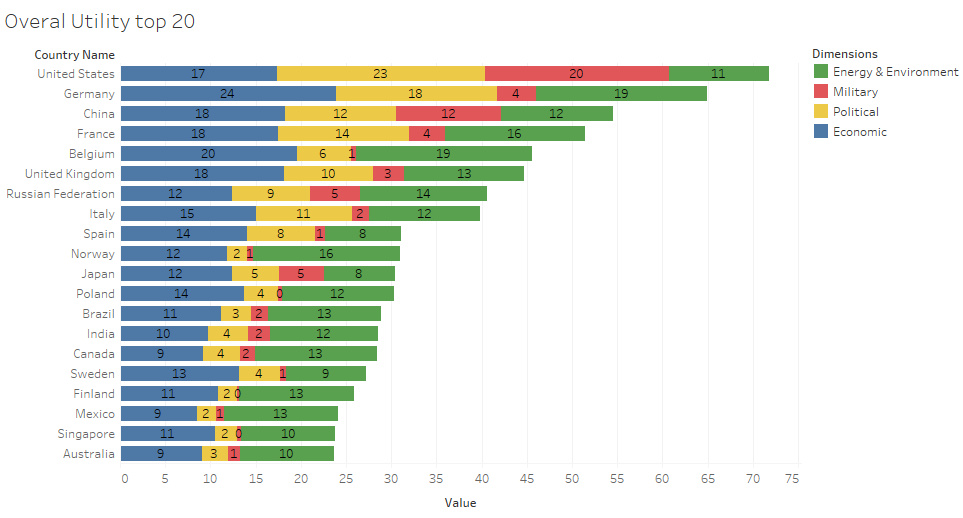

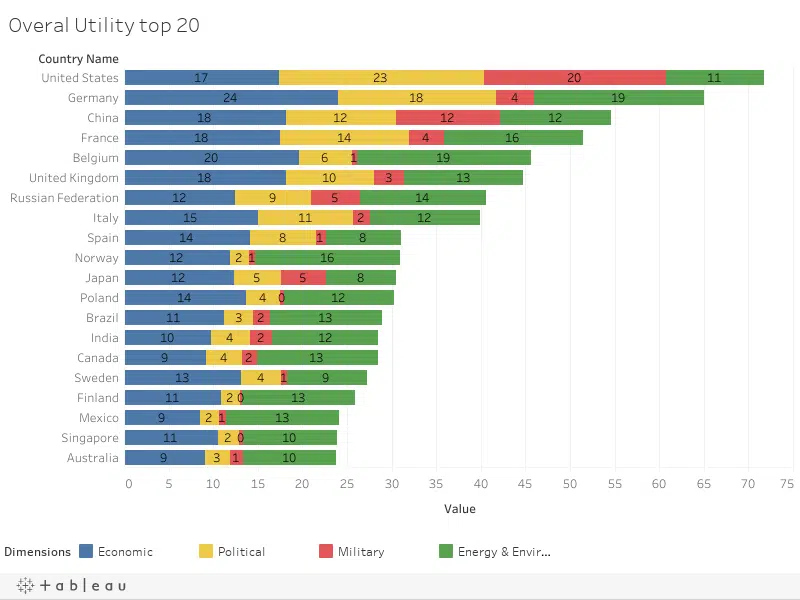

Top 20 strategically important countries (Utility, 2016)

Analytical Support for International Cooperation Choices for the New Dutch Government Coalition

The new Dutch coalition agreement, which was unveiled on October 11, 2017, delineates a set of foreign policy goals for the next four years. The agreement speaks of the coalition’s intention to pursue ‘a realistic foreign policy that serves both Dutch interests and the international rule-based order’ [1]. As part of this, it proposes a security strategy that integrates national and international security challenges; pledges to work through international organizations such as the EU, NATO and the UN; and proffers to focus on EU neighbouring countries and Europe’s ‘ring of instability’ [2]. It commits to increasing the defense budget, strengthening the Dutch armed forces and establishing closer military partnerships with ‘like-minded countries’ [3]. It also announces an upcoming review of the selection of so-called ‘focus countries’ in Dutch development cooperation policies ‘in light of the new objectives of foreign policy in order to bring about more focus and effectiveness’ [4]. The coalition’s plans foreshadow important decisions about the countries with which the Netherlands will actively seek closer or less close relationships.

These decisions involve choices and trade-offs that may not be easy, but are nonetheless necessary [5]. The Netherlands’ government aspires to safeguard Dutch interests and values globally. Given the limited resources that are available for this goal, however, it needs to pick and prioritize [6]. The National Security Strategy, the International Security Strategy and the Defense Note Houvast in een Onzekere Wereld provide elements that help in articulating and prioritizing these efforts by identifying critical interests and outlining potential risks. They do not, however, contain a systematic framework to guide partnership prioritization [7]. In order to provide an analytical basis for such a framework, HCSS is developing a Dutch Foreign Relations Index (DFRI) which reflects the traditionally dual orientation of Dutch foreign policy: the pursuit of Dutch interests on the one hand and the adherence to and promotion of norm-based values on the other [8].

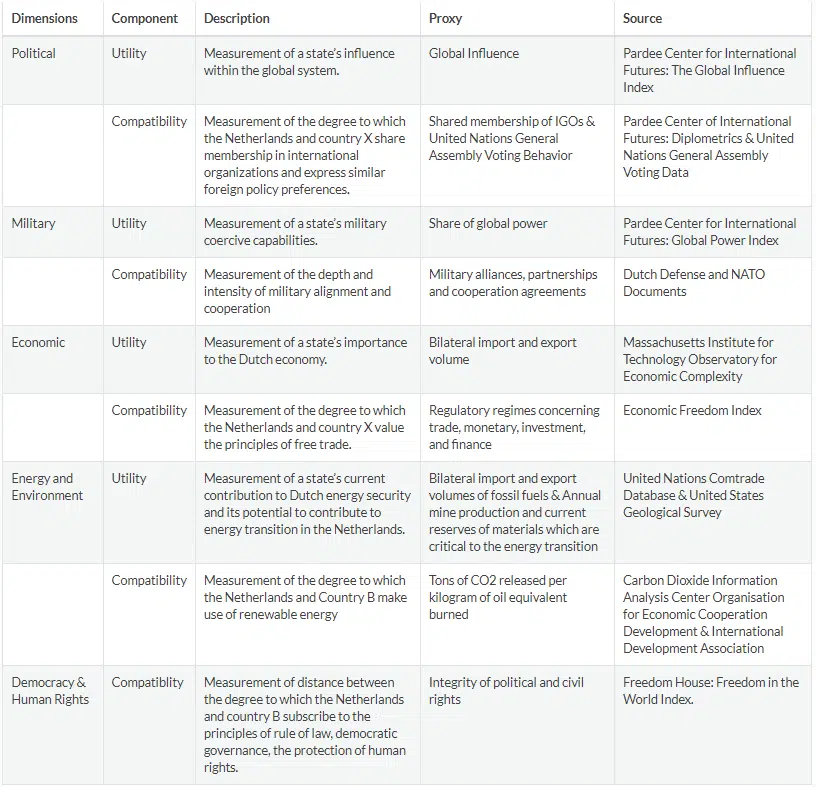

The DFRI distinguishes between a country’s utility (“how important is a country for the Netherlands in terms of interests?”) and compatibility (“to what extent does it share similar values?”). Each of these two dimensions incorporates an assortment of economic, political, military, energy & environment, and (in the case of compatibility) democracy & human rights-related indicators [9]. The utility variable makes it possible to rank countries on the basis of their current importance to Dutch interests. High-utility countries are important, but their values may not always correspond with those of the Netherlands. The DFRI addresses this by also including a country’s compatibility, which measures the distance between the Netherlands and other countries in terms of values. This allows us to gauge the degree to which these countries’ worldviews align with the Netherlands. Combining utility and compatibility on the basis of a 1995-2016 dataset thus allows us to identify clusters of countries that vary in both their utility and their value compatibility. This in turn can help inform partnership choices by providing the analytical and empirical basis [10]. Table 1 below shows the indicators, data and data sources used to construct the DFRI.

This Alert presents the findings of a high-level analysis of this first current iteration of the DFRI. It offers, from the Netherlands’ perspective, an overview of the utility and compatibility of states worldwide and the changes therein over time. It also derives clusters of countries based on a combination of these two dimensions. It concludes with suggestions as to how the DFRI could be further developed and leveraged as an analytical input into the partnership prioritization process in Dutch official foreign and security policy making.

Before we turn to the analysis, we would like to add some caveats up front.

As with every Index, the results obtained through the DFRI are based on proxy indicators. ‘Economic utility’, for instance, is an abstract concept that can not be captured directly. What we can (and – in this index – do) do, however, is to capture and track discernible developments in a number of concrete and measurable manifestations of this abstract concept. Such measurements always remain far from perfect, first and foremost because they are simplified representations of a much more complex reality which occasionally also yield false positives and do not control for other potentially relevant factors [12]. Furthermore, they do not reflect all manifestations of the abstract concepts they try to capture. In the economic dimension of the DFRI, for instance, we do not account for global value chains and the different values added along each node of the chain, nor do we include foreign direct investments, even though we realize that these are important elements. Finally, indices are often not comprehensive in terms of the dimensions that are considered. The current iteration of the DFRI does not include such dimensions as education or innovation, which may limit explanatory power at micro as well as macro levels. These caveats notwithstanding, we remain convinced of the need to create and exploit ever more reliable evidence-based tracking tools for these important aspects of international interactions. We plan to continue iterating on the included indicators in the future and welcome any feedback that would help in improving the index and its underlying components.

Which countries are strategically important to the Netherlands? The 2016 top-20 list of this first iteration of the DFRI reveals a distinct set of countries, which include the major economic and political powers in the current international system as well as a set of medium- and smaller-sized powers. Close allies such as the United States and Germany populate the top tier with China as a close runner up. The other three BRIC countries also appear on the list with Russia in the top-10, and India and Brazil in the top-20. Larger EU member states, including France, Great Britain, Italy and Spain, are represented, as is Poland. The presence of Norway, Sweden and Finland highlight that the traditionally close relationship between the Netherlands and the Scandinavian peninsula persists to this very day. Japan, which continues to be one of the largest economies in the world, features amongst the high-utility states, as do Canada, Mexico, Singapore and Australia. With the exception of the United States and to a lesser extent Germany, the underlying indicators of the majority of high-utility countries tend strongly towards high scores in the economic and energy & environment-related areas, which reflects the Netherlands role as a trading nation.

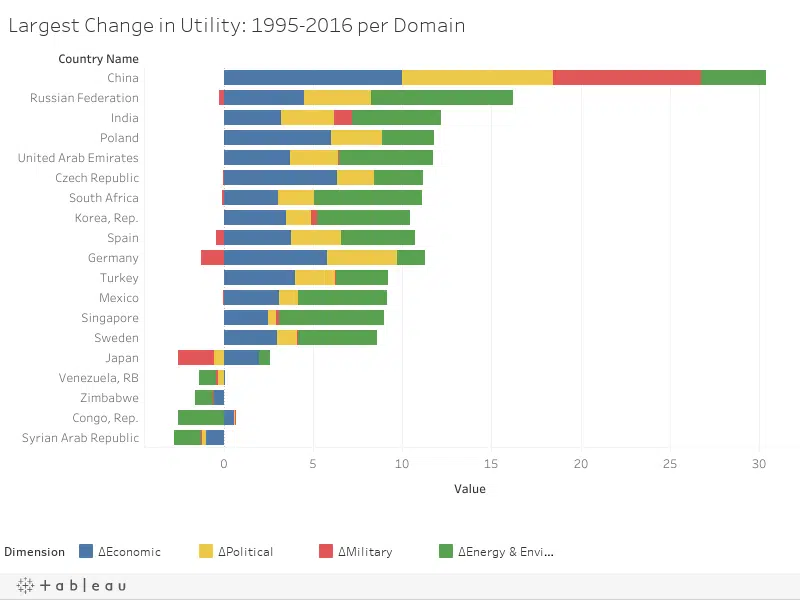

The next visual (see Figure 2) shows the list of countries exhibiting the highest (positive and negative) changes in utility between 1995 and 2016. It reveals a number of notable developments.

The general composition of the top-15 risers incorporates a mix of Central European (Czech Republic, Poland) and oil-trading countries (Russia, the UAE, Iraq, and Singapore in particular). The fact that all of the top-5 risers (China, Russia, Iraq, India, and South Korea) are non-Western countries is unsurprising. Many Western countries (U.S.A., France, Belgium, etc.) already obtained high utility scores in 1995, and simply had considerably less potential for growth in this area than countries which (in 1995) lacked robust trade relationships with the Netherlands and/or the material resources to build up their coercive capacities. This does not necessarily indicate that Western countries are stagnating, but does offer some evidence to support the notion that the world is becoming multipolar, which in turn is reflected in the utility growth of particular countries for the Netherlands. Both China and South Korea provide topical illustrations of this dynamic. An obvious exception to this rule presents in the case of Germany, which derives a considerable share of its increased utility vis-à-vis the Netherlands from growth in bilateral trade volume. Berlin was already (relatively) utile to the Netherlands even in 1995, but the registered increase between these two neighbors also reflects increased intra-EU trade volumes in general.

Outside of China – which has recorded significant increases across the board – increases in country utility stem almost exclusively from increasing volume in trade of goods, services, and energy vectors. Decreases in the military utility of Japan and Germany appear significant, but are largely an artifact of the Global Power Index’s conceptualisation of military power as a zero sum game [13]. The absolute value of these countries’ military utility has increased, but is offset in relative terms by China’s stunning rise along this dimension. Net decliners (Venezuela, Zimbabwe, the Republic of Congo, and Syria) are all countries whose ability to interact with the world (whether economically or otherwise) has been hampered by the onset of domestic crises and/or civil wars.

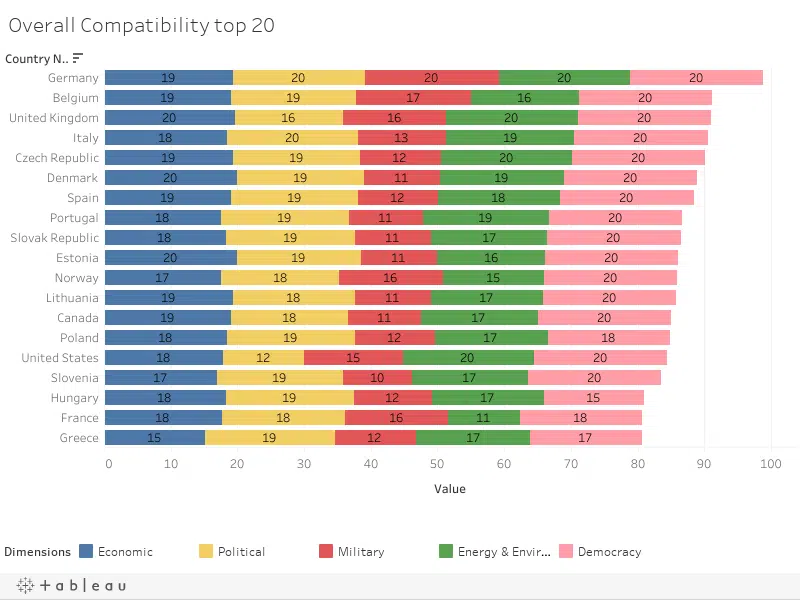

Figure 3 presents the 2016 top-20 of countries that are most compatible with the Netherlands. The most striking observation is that the compatibility dimension is generally distributed far more equally than the utility one. We hasten to add that this is to a large extent due to the (annual) normalization process used to construct this dimension. This ensures that the list of the top-20 most compatible countries contains by-and-large predictable actors, and is populated almost exclusively by EU and/or NATO member states, or close affiliates thereof. Still, this finding is not just a statistical artefact but really reflects the fact that shared membership in IGOs such as the EU and NATO tends to reflect norm socialization and the adoption of shared policies and practices.

Outliers here include Greece, Hungary, and the United States. These respectively perform lower on the economic and democratic compatibility indicators in 2016. This can be explained by the Greek austerity crisis and the ongoing process of democratic deconsolidation under Prime Minister Orbán in Hungary. Although the performance of Hungary and Greece is largely unsurprising, the United States’ deviation warrants further discussion. Its low compatibility score is caused by diverging voting behavior in the UN General Assembly. Military compatibility is by far the least evenly distributed. This is because in addition to strong partnerships with NATO and EU members, the Netherlands has established a series of military cooperation initiatives with a number of states that include Germany, Belgium, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

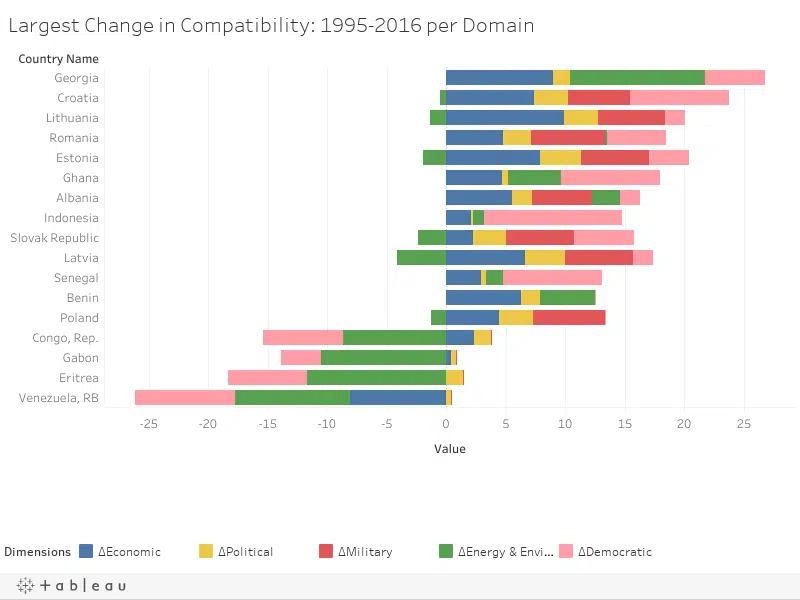

Turning our attention to the changes between 1995 and 2016 (see Figure 4), we see that large shifts in compatibility have taken place.

These shifts almost all relate to either democratization in some countries or democratic deconsolidation in others. Among the largest net risers in compatibility are a number of former Soviet bloc states that joined the European Union, as well as a few African countries (such as Ghana and Senegal). These countries’ appearance in this list is due to their low 1995-baseline score, particularly in the democracy & human rights domain. Several countries (Indonesia, Sierra Leone, Croatia) had low baseline democratic scores at the beginning of the time series, and owe their sizeable compatibility gains largely to the strides they have since made towards democratization. The exception here is Georgia, which derives uncharacteristically large compatibility increases from its better scores in economic and energy & environment. These increases can be attributed at least partially to the trade-and-democracy constricting civil war in which it was embroiled until 1993, depressing its baseline values in 1995.

The democratic variable also contributes significantly to the slide of several countries’ compatibility. The net compatibility-receders are almost all states ruled by autocratic/illiberal regimes such as Venezuela, Congo, Eritrea and Gabon.

It is also worth noting that countries gaining compatibility with the Netherlands in the energy & environment domain are (by-and-large) industrialising states. These are generally moving down towards the Netherlands’ relatively poor performance on the CO2 per kilograms of oil equivalent measurement [14], and therefore become more compatible.

Using the DFRI, Figure 5 plots utility against compatibility and gauges the position of countries worldwide vis-à-vis the Netherlands. At the most general level, the DFRI reveals several distinct trends over the period 1995-2016. The first is that some of the world’s largest economies tend to increase in utility without changing much in terms of compatibility. Dealing with this discrepancy may prove to be one of the main foreign policy challenges for the current and future government coalition in the Netherlands (and beyond) – reflecting former US National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski’s choice between ‘power’ and ‘principle’ [15]. This choice has been certainly topical in the Dutch foreign policy discourse in recent years [16].

Secondly, medium sized economies, especially those located in or near Europe, exhibit strong growth in terms of compatibility. This effect is particularly pronounced in countries that have joined the European Union since 1995. These countries, which include the Baltic states, and Central European States such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia, also consistently experience large increases in utility shortly after their compatibility spikes: they gain access to the EU’s single market and begin to increase their trade volume. Countries with relatively smaller economies, a low-to-medium degree of compatibility with the Netherlands, and no European membership status tend to oscillate in the middle on both axes. This may be indicative of inconsistent reforms and regime change.

Russia and China both display considerable increases in utility from the late 1990s onwards. Russia slows down from 2008 onwards, while China continues to record growth until 2014. China is remarkably static as far as compatibility is concerned, but Russia sees significant reductions circa 2014 [17]. Moscow’s drop in compatibility coincides closely with the 2014 collapse of oil prices. Russia’s drop in democratic compatibility during this period (a reduction of 0.8, or approximately 20%) illustrates the notion that economic contraction can be tied to governmental curtailing of civil rights. With regards to other relevant economies (specifically Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, and India), these almost universally display incremental increases in both utility and compatibility over time. Mexico’s increase in compatibility presents almost entirely between 1995 and 2000, while Brazil, Indonesia, and India remain relatively stable. In these cases, the positive effects of increases in democratic and economic compatibility are often dampened by reductions in environmental compatibility. Aside from Indonesia, all countries experience sizeable reductions in energy & environment utility around 2013/2014. This is because falling oil prices during this period causes the absolute value of trade in these resources to decline.

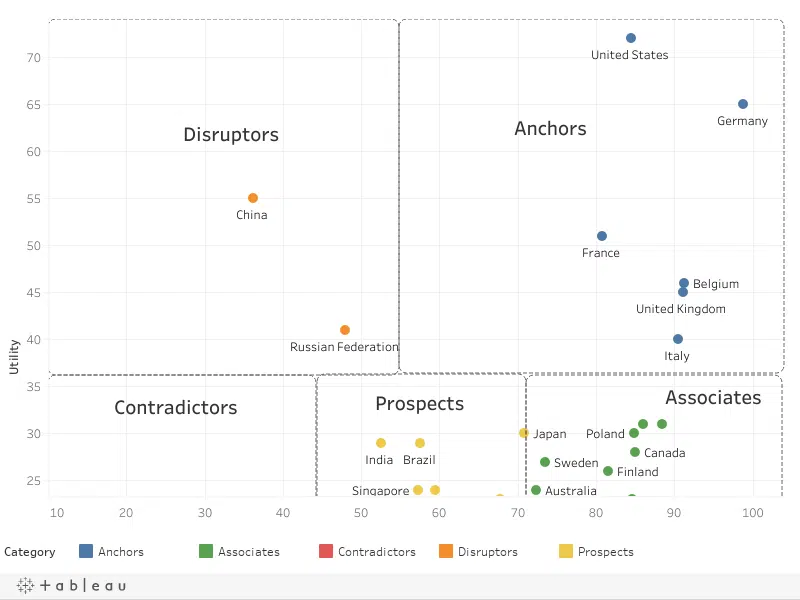

Looking just at the situation in 2016 shows considerable variation in the utility and compatibility of countries. The Netherlands’ values align closely with many of the countries with high utility scores (in the upper right quadrant of the chart), as well as with a slightly larger number of countries with high compatibility but lower utility scores (lower right quadrant of the chart). On the other side of the spectrum, China and Russia are the two most conspicuous countries with high utility but relatively low compatibility (upper left quadrant). A diverse assortment of countries have low utility and low compatibility (lower left quadrant) while there is also a sizeable cohort of countries with low-medium utility and medium compatibility (middle bottom of the quadrant). Based on a clustering exercise in which we consider the combination of a country’s utility and compatibility score [18], we identify five country categories: anchors, associates, prospects, contradictors and disruptors (see Figure 6).

Anchors

Countries which fall within this category combine high utility with high compatibility vis-à-vis the Netherlands. They are important states for a mixture of political, military, and economic reasons, and share largely similar worldviews. They can be regarded as anchor states from The Hague’s perspective. The Netherlands currently has 6 of them: the United States, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Italy. Note that the group is not only populated by large economic powerhouses such as the United States, Germany, and France; the smaller Belgium is also included because of the degree to which the two countries cooperate economically. For now it remains an open question whether Brexit will lead to significant reductions in the United Kingdom’s utility. Post-Brexit changes in compatibility are certainly possible, although they are by no means preordained and much will depend on the outcomes of the ongoing negotiations. All this being said: the list of indispensibles aligns with expectations – anchor states from the Netherlands’ perspective are neighbouring countries, regional economic powerhouses, and the world’s largest military power – a critical European security provider. Interaction is (in most domains) fairly robust. These countries warrant continued efforts at maintaining the relationship.

Associates

Associates are highly compatible with the Netherlands, but – either because they have relative little coercive capacity or international influence, have limited economic interaction with the Netherlands, or preside over few natural resources – have limited current utility. The associate category includes the Scandinavian countries, transitioned (Eastern) European states, Southern European states (Spain and Portugal), and Commonwealth countries such as Australia and Canada. Turkey and Poland’s inclusion within this category derives largely from the one-year time delay associated with the updating of the Freedom in the World Index [19]. Several associates have significant potential utility: Norway and Canada arguably have as much potential (and perhaps more) utility than countries such as Belgium and Italy, but simply don’t (currently) interact with the Netherlands enough to be classified as anchors. Given the fact that like-minded associates are characterized by high compatibility, the ground is objectively fertile for future growth in utility. Due to variations in potential utility within the category, the potential benefits associated with fostering increased compatibility (or leveraging current compatibility) should be analysed on a state-to-state basis.

Prospects

The prospects category includes states which combine medium compatibility scores with utility scores that range from low to average. It is important to note that these states’ limited utility often reflects the Netherlands’ relative lack of engagement with them, and that potential utility frequently far surpasses the current score. Prospects comprise of upcoming economies such as Brazil, India and Indonesia, as well as an assortment of Latin American, Middle Eastern and African countries, and a few well-developed economies (see for example Japan and Israel). Owing to the fact that they are both relatively compatible with the Netherlands and relatively untapped by the Netherlands, they constitute potentially interesting outreach partners. The cost-benefit potential surrounding these states may, in other words, well be positive: the Netherlands can invest in closer economic ties, can commit to fostering deeper diplomatic ties, and can (in select cases) aspire towards cooperating more closely militarily. Because some of these countries (including but not limited to Mexico, Brazil, India, Indonesia) have large, growing and energy-hungry populations, it is also in the Netherlands’ best interest to engage with these countries on environmental issues.

Contradictors

Contradictors combine low overall utility with low compatibility. The contradictor category includes countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Venezuela, various -Stans (Turkmenistan, Tajikistan), South East Asian states such as Cambodia and Vietnam, and a number of important African states such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. They are almost universally autocratic, and often do not directly interact with the Netherlands at any significant level measured in the DFRI. This is not to say that they are not important. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela preside over large reserves of natural resources (they have high potential utility), but – partially because they do not maintain a significant trade relationship with the Netherlands – do not score high enough in utility to transpose their resources into the potential leverage necessary to classify them as disruptors. The low compatibility scores of some of these contradictors also makes them potentially viable recipients of value-based development cooperation policies which aim to improve democratic governance and to protect minority rights.

Disruptors

The category disruptors comprises of two states: China and Russia. The two disruptors combine medium-to-low compatibility with high utility. These states have sufficient clout to contribute to shaping trends in the international system – whether passively or actively. Because their values diverge either partially or fundamentally from those held by the Netherlands in the areas of human rights, the role of governments in the regulation of economies, and the international rule of law, their actions, especially in these domains, may be at odds with Dutch policies and may also run counter to Dutch strategic interests. This does not mean that these states should be seen as dead-end targets for outreach efforts. On the contrary, the high utility of China and Russia is partially indicative of an high degree of bilateral interaction particularly in the economic and environment & energy domains with the Netherlands. This interaction should not necessarily be abrogated because it can foster mutually beneficial interdependence, while at the same time being instrumental to the attainment of important environmental objectives. Simultaneously, efforts to reduce the Netherlands’ dependence on these countries through diversification should continue to be pursued.

Foreign and security policy makers can and should leverage the increasing availability of empirical datasets in their decision making. The DFRI Index introduced in this Alert provides one such analytical input to put discussions relating to the maintenance (and forging) of Dutch partnerships on firmer empirical footing. In line with the dual orientation of Dutch foreign policies, reflected in the new Coalition’s Agreement, this entails a need to not just recognize the importance of values and interests, but to also operationalize them. On that basis, it is possible to assess which countries have similar values, which countries have diverging values, and which countries are important in light of Dutch vital national interests.

The current iteration of the DFRI marks a small but – from our perspective – useful step in that direction. This Alert has provided the first-order analysis of the first-ever DFRI. On the basis of the identification of a number of important interests and values, it has looked at the big picture of Dutch foreign relations, considering trends therein over time and singling out candidates for various types of partnership initiatives. It should go without saying that further refinements and in-depth analyses are necessary. Such improvements will include new indicators for currently under-emphasized aspects of utility and compatibility; will consider differences and similarities along and across the individual political, military, economic, energy & environment and democracy & human right sub-components; and will track changes therein over time. It also will try to further bridge the gap between strategic analysis and policymaking by further incorporating and elaborating specific priorities of the new coalition and by focusing both the analysis and the policy recommendations on that basis. Here it will be important to further distinguish between current and potential utility and compatibility, to identify not only current partners, but also potential promising partners for specific purposes, from within a forward looking perspective.

In short, this contribution is part of HCSS’ foundational effort to infuse Dutch (but also other countries’) foreign policy debates with more conceptual and empirical clarity and to provide Dutch (and other countries’) policymakers with a toolbox to prioritise policy efforts that maximize national interests and promote its values. The Netherlands’ historical track record is one that by valuing evidence-based pragmatism over ideological debates has been able to further both its interests and values despite its small size. This attitude has served the country well and continues to be – in our assessment – an important asset for its future security and prosperity.

Must reads for Vital European and Dutch Security Interests

Reflectie op regeerakkoord Rutte III – Clingendael Institute

Better together: Towards a New Cooperation Portfolio for Defense – The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies

Strategic Choices for a Turbulent World – RAND Cooperation

Policy Brief: a shift in European security interests since the EU Global Strategy? – Clingendael Institute

EU Enlargement: Door Half Open or Shut? – Centre for European Reform Europe’s Illusionaries – Carnegie Europe

Authors: Tim Sweijs, Hugo van Manen, Paul Verhagen, Stephan De Spiegeleire

Contributors: Erik Frinking & Karlijn Jans

About the Monthly Alert

In order to remain on top of the rapid changes ongoing in the international environment, the Strategic Monitor of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence provides analysis of global trends and risks. The Monthly Alerts offer an integrated perspective on key challenges in the future security environment of the Netherlands along the following four themes:

- Vital European and Dutch Security Interests

- New Security Threats and Opportunities

- Political Violence

- The Changing International Order

The Monthly Alerts reflect the monitoring framework of the Annual Strategic Monitor report, which is due for publication in January 2018. Each Monthly Alert offers a selection of discussions of emerging developments by key stakeholders in publications from governments, international institutions, think tanks, academic outlets and expert blogs, supported by previews of ongoing monitoring efforts of HCSS and Clingendael. The Monthly Alerts run on a four-month cycle alternating between the four themes.

Disclaimer

This Report has been commissioned by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence within the PROGRESS framework agreement, lot 5, 2017. Responsibility for the contents and for the opinions expressed rests solely with the authors; publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence.

References

- Kabinetsformatie, 2017. “Vertrouwen in de toekomst”, p.47. https://www.kabinetsformatie2017.nl/documenten/publicaties/2017/10/10/regeerakkoord-vertrouwen-in-de-toekomst↩

- Kabinetsformatie, 2017. “Vertrouwen in de toekomst”, p.48. https://www.kabinetsformatie2017.nl/documenten/publicaties/2017/10/10/regeerakkoord-vertrouwen-in-de-toekomst↩

- Kabinetsformatie, 2017. “Vertrouwen in de toekomst”, p.49. https://www.kabinetsformatie2017.nl/documenten/publicaties/2017/10/10/regeerakkoord-vertrouwen-in-de-toekomst↩

- Kabinetsformatie, 2017. “Vertrouwen in de toekomst”, p.50. https://www.kabinetsformatie2017.nl/documenten/publicaties/2017/10/10/regeerakkoord-vertrouwen-in-de-toekomst↩

- Rob de Wijk et al., “Een kompas voor een wereld in beweging | HCSS” (The Hague Centre For Strategic Studies, February 27, 2017), https://hcss.nl/report/een-kompas-voor-een-wereld-beweging.↩

- As also argued on page 8 of Rob de Wijk et al., “Een Kompas Voor Een Wereld in Beweging: De Rol van Buitenlands Zaken in Het Borgen van Nederlandse Belangen” (Den Haag: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2017)↩

- For the relevant docs on the SNV, see here. For the original SNV see Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties, “Strategie nationale veiligheid – Kamerstuk – Rijksoverheid.nl,” kamerstuk, May 14, 2007, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2007/05/14/strategie-nationale-veiligheid. For the IV, see Ministerie van Algemene Zaken, “Beleidsbrief Internationale Veiligheid – Turbulente Tijden in een Instabiele Omgeving – Kamerstuk – Rijksoverheid.nl,” kamerstuk, November 14, 2014, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2014/11/14/beleidsbrief-internationale-veiligheid-turbulente-tijden-in-een-instabiele-omgeving.; see also Ministerie van Algemene Zaken, “Veilige wereld, veilig Nederland – Internationale Veiligheidsstrategie – Rapport – Rijksoverheid.nl,” rapport, June 21, 2013, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2013/06/21/veilige-wereld-veilig-nederland-internationale-veiligheidsstrategie. For the Defense note, see Ministerie van Algemene Zaken, “Meerjarig perspectief krijgsmacht: Houvast in een onzekere wereld – Rapport – Rijksoverheid.nl,” rapport, February 14, 2017, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2017/02/14/meerjarig-perspectief-krijgsmacht-houvast-in-een-onzekere-wereld.↩

- The joint interest and values based approach of the DFRI derives from a long tradition of Dutch foreign policies that combines the pursuit of Dutch interests with a strong emphasis on values. See Duco Hellema, Nederland in de Wereld, 2014, http://www.unieboekspectrum.nl/boek/9789000334995/Nederland-in-de-wereld/.; J. J. C. Voorhoeve, Peace, Profits and Principles: A Study of Dutch Foreign Policy (M. Nijhoff, 1979). See also Rob de Wijk et al., “Een kompas voor een wereld in beweging | HCSS” (The Hague Centre For Strategic Studies, February 27, 2017), https://hcss.nl/report/een-kompas-voor-een-wereld-beweging. The goals outlined in the Coalition Agreement as well as in key national security and strategy documents published by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security and Justice clearly express this commitment to a mixture of values and interests. For the key documents, see the sources in previous footnotes.↩

- For a brief overview of DFRI methodology, refer to here↩

- HCSS has emphasized the importance of the analytical preparation of political decisions about cooperation choices in previous studies. In our 2016 Better Together study, we observed that “partnership choices are typically thought to belong to the realm of politics, based on political preferences. This report argues they should rather be seen as value-for-money choices. Decisions should be made on the basis of a pragmatic, pre-political, pre-bureaucratic analysis that considers the various cooperation options that are available and then designs a portfolio of cooperation partners and forms that will enable a [government] to navigate very different futures”. See Willem Oosterveld, Stephan De Spiegeleire, and Frank Bekkers, “Better Together: Towards a New Cooperation Portfolio for Defense | HCSS” (The Hague Centre For Strategic Studies, July 21, 2016), https://hcss.nl/report/better-together-towards-new-cooperation-portfolio-defense↩

- For a more detailed description of the indicators and underlying data, see methodological note↩

- False positives in proxy measurements generally result when other factors than the proxied-for phenomenon affect the results recorded by the proxy. An example of this can be found under the DFRI’s energy & environment domain, which measures a combination of bilateral trade in fossil fuels, mine outputs, and reserve size and CO2 released per kilogram of oil equivalent burned to operationalize utility and compatibility respectively. These measurements are chosen due to (in part) a lack of viable alternatives. For instance, we did not manage to locate datasets that offer information on countries’ climate policies that had a) global coverage and b) covered the time period under consideration. We decided to use the CO2 released per kilogram of oil equivalent burned as a proxy for government policy vis-à-vis renewable energy – even though we are aware of the fact that it is far from perfect. The value of the CO2 measurement included may be inflated by (among others) natural phenomena such as melting permafrost. Such inflation is not necessarily representative of (in this case) the Canadian government’s policies vis-à-vis renewable energy, and may occasionally render the proxy ineffective.↩

- The GPI expresses a country’s share of global power (% of world total) on an annual basis. Increases in the absolute values of underlying indicators only increase one country’s share of global power if the increases are relatively larger than the increases recorded in other countries.↩

- SeeEurostat, “Renewable Energy Statistics – Statistics Explained” (European Commission, June 2017), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Renewable_energy_statistics. ;Edward Vixseboxse, Bart Wesselink, and Jos Notenboom, “The Netherlands in Europe: Environmental Perfomance in Perspective” (Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, 2006), http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/mnp_2006_-_ebi_background_article.pdf.↩

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977-1981 (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1983).↩

- Remco Meijer Hoedeman Jan, “VVD Wil Meer Samen Optrekken Met Dictators – Binnenland – Voor Nieuws, Achtergronden En Columns,” De Volkskrant, March 28, 2015, https://www.volkskrant.nl/binnenland/vvd-wil-meer-samen-optrekken-met-dictators~a3930948/.;Halbe Zijlstra, “RealistischBuitenlandbeleid-HalbeZijlstra.pdf,” accessed October 18, 2017, https://legacy.gscdn.nl/archives/images/RealistischBuitenlandbeleid-HalbeZijlstra.pdf.;Adviesraad Internationale Vraagstukken, “Adviesraad Internationale Vraagstukken,” accessed October 18, 2017, http://aiv-advies.nl/69b/publicaties/adviezen/nederland-en-de-arabische-regio-principieel-en-pragmatisch.;Sjoerd Sjoerdsma, “Ook Vrijheid Voor ‘Stabiele Regimes’ – Opinie – Voor Nieuws, Achtergronden En Columns,” De Volkskrant, April 2, 2015, https://www.volkskrant.nl/opinie/ook-vrijheid-voor-stabiele-regimes~a3942170/.↩

- Frank Bekkers and Stephan De Spiegeleire, “From Assertiveness to Aggression | HCSS” (The Hague Centre For Strategic Studies, June 16, 2015), https://www.hcss.nl/report/assertiveness-aggression.↩

- Each actor category is driven by a mathematical criteria; the utility axis is divided into the two categories, those below and those above the center of the range 0-72. The compatibility axis is divided into quartiles. Each category corresponds to a set of constraints. For further information see the methodological note.↩

- Turkey’s descent is in fact already visible in our time series analysis.↩