Research

Political violence is real and present. How, why and when political violence manifests itself is crucial for turning early warning into early action. The earlier decision- and policymakers are made aware of the potential for imminent outbursts of violence, the sooner they can act to manage or mitigate the consequences or even deter the occurrence altogether. With a wealth of data and models available, it is time to reap the fruits of the data revolution. Looking at the HCSS Political Violence Monitor: what are the 10 countries most at risk of civil wars, coup d’états or state led mass killings?

Violent and deadly crackdowns on mass protests in Caracas, tanks rolling down the Bosphorus bridge in Istanbul and the suppression of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar – political violence is real and present. The catastrophic loss of life in Rwanda in 1994, Bosnia in 1995 and Darfur in 2003 were in part the result of failures to heed the early warning signs. Understanding how, why and when political violence manifests itself is crucial for turning early warning into early action. The earlier decision- and policymakers are made aware of the potential for imminent outbursts of violence, the sooner they can act to manage or mitigate the consequences or even deter the occurrence altogether. With a wealth of data and models available, it is time to reap the fruits of the data revolution.

Political violence may be categorized into different types, out of which we examine the following: civil wars (we provide both long- and short-term risk assessments), where open warfare between rival factions occurs; coup d’etats, typically a more localized effort to overthrow a government directly; and state-led mass killings, where concerted efforts are made to violently persecute a certain group of people within the country. Each mode of political violence has different drivers, indicators and contextual backgrounds. By drawing from a wealth of slowly changing structural data and increasingly using more dynamic, event-based data, our models assess the risks of different types of political violence and also show the drivers of risk in particular countries.

Over the past decade, many disciplines increasingly use extensive computer modeling, with some approaches being theory-driven and confirmatory and others explorative. For example, the Paris Accord and other environmental negotiations were informed by elaborate climatological models and central banks use financial models and projections to raise or lower interest rates. Modelling and risk assessments are also being put to use in the field of international relations. The Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), built by Lockheed Martin and used by the Pentagon is one of a number of automated event databases, along with GDELT and Phoenix, that allows for continuous monitoring of events of a political nature around the world. The Early Warning Project funded by The American Holocaust Memorial Museum, ViEWS project run by Uppsala University and the CRISP model by WardLab are only some of the recent efforts in assessing the risks of the onset of political violence. Using a data-driven approach complemented by a substantive understanding is the key to a smart policy making process that is dynamic and anticipatory rather than reactive.

| Risk Assessment vs Predictions The HCSS continuously works on political violence risk assessment research and has developed a portfolio of monitors by learning from crucial research done by the leading industries and scholars, while adding our own subject matter expertise and new features, such as the application of event data to make the risk assessment more current and accurate. The output of the models, however, are a risk assessment based on best publicly available data, not a prediction of future events. Events on the ground can change rapidly, such as before the Arab Spring in 2011, changing the risk assessments on a daily basis in a short-term assessment, but not affecting the assessment that is based on long-term, structural data. The numerical values of our assessment should be interpreted as relative risk: that is, the likelihood of onset of political violence is higher in the countries with higher risk scores compared to those with lower scores, while there is still much uncertainty about the actual likelihood of onset in absolute terms, an example being the probability of coup d’etat in a particular country in the coming year. The main challenge in the field being the rarity of the events, which makes the risk assessment more difficult. Considering all this, the statistical risk assessment should always be combined with more qualitative expert understanding of the regions or countries in question. |

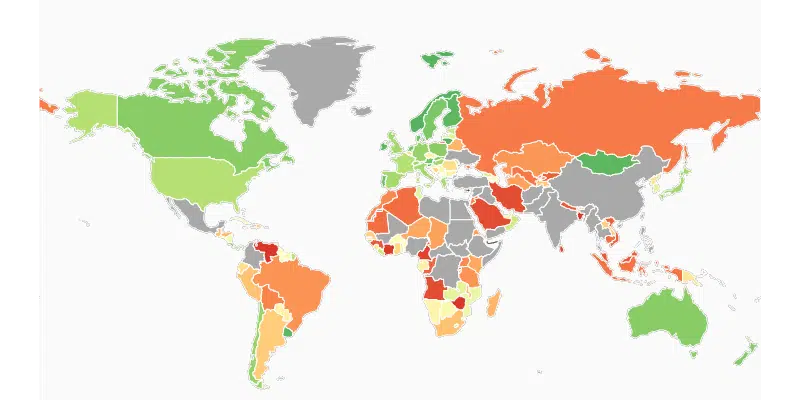

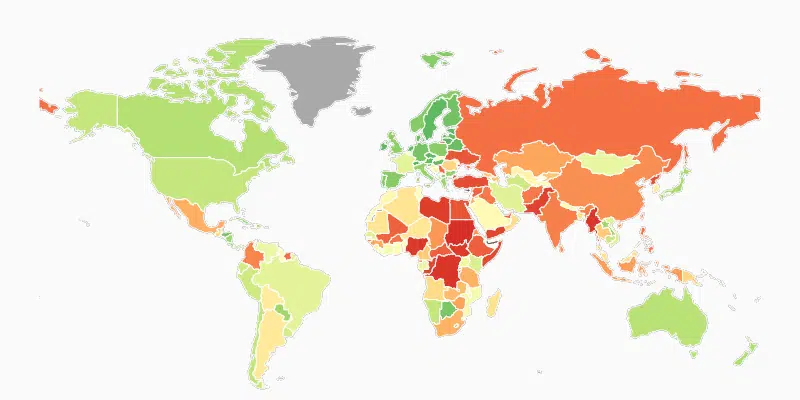

Our general approach is uniform for all the types of political violence we studied – namely we look at the risk of onset of new episodes, with the risk scores being between 0 and 100. The risk score indicates relative risk: to which percentile a country belongs to according to our assessment; with 100 implying belonging to the top percentile, and 50, for example, belonging to the 50th percentile. For the civil war risk assessment, countries which currently already have some ongoing conflicts are excluded, as are countries with a population of under 500,000 people, both are shown as gray.

In December of 2010, a 26 year old street vendor set himself on fire in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, after police confiscated his wares. His suicide had consequences reaching far beyond Tunisia, and set into motion a sequence of events and mass protests across the MENA region that would become known as the Arab Spring. Similar single events can tip a country into civil war, but only if long standing structural injustices and socioeconomic inequalities have already weakened the social fabric of a country.

To assess the risk of civil war, we use two approaches. The first combines structural indicators such as regime type and infant mortality with real-time event data based indicators, such as activities of rebel and insurgent groups. The second uses different combinations of structural indicators. The results of the first approach, which offer a more short-term perspective, are shown here, followed by the long-term approach in the next section.

We observe that virtually all of the countries in the top ten are (semi-)autocratic or hybrid regimes, with those that are ostensibly democracies holding either contested elections or handpicking candidates eligible for public office. Our assessment shows that the countries ‘in the middle’ – which are neither full autocracies or democracies, rather having a hybrid regime with severe incompatibilities between government and opposition – are quite often in the highest risk category.

Bangladesh, Côte d’Ivoire, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Cameroon and Iran have all recently experienced violent attacks, either in the form of terrorism or motivated by ongoing ethno-religious tensions, that have contributed to their high ranking. The presence of large, well-equipped armed groups that fall outside the control of the government are a strong factor in determining the risk of civil war erupting.

In both Iran and Lebanon, violence is spilling over from the ongoing Syrian conflict and instability in Iraq, while Cameroon is dealing with Boko Haram active in their region. Côte d’Ivoire has seen military personnel, disgruntled over pay, open fire in numerous cities.

For another set of countries, it is primarily political or economic reasons that are driving the risk of civil war. Those include Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Angola and Saudi Arabia. All but Zimbabwe are highly dependent on oil, and as its price has taken a tumble, these governments have struggled to fund the subsidies that smoothed over deep-seated dissatisfaction with their governments in the past. Venezuela has seen the total collapse of its economy and widespread scarcity in the most basic consumer goods, leading to violent mass protests in the streets of major Venezuelan cities. Saudi Arabia is fighting a costly war in Yemen while trying to diversify its economy away from oil production. Meanwhile, Angola and Zimbabwe have seen large revenues from natural resources squandered by corrupt officials and inefficient governance resulting in some of the highest inequality, child mortality and lowest life expectancy figures in the world.

Outlook

The prospects for most of these countries look grim, but if they can overcome key challenges, they might yet stave off further escalation. For the countries dealing with violent insurgent groups that test the government’s ability to maintain order, the challenge is to extend political representation for ethnic or religious minorities. The countries facing problems of an economic nature should implement sweeping economic reforms, but doing so will require deep cuts to sectors that have kept the country precariously balanced.

For more information regarding methodology, click here.

| Close-up: Venezuela Venezuela sits on the single largest oil reserves in the world and has historically been a major exporter of oil. Close to 90% of total exports from Venezuela is attributable to oil, and the total share of GDP that depends on oil is similarly large. This heavy dependence on oil revenues has proven to be both a boon and a curse for Venezuela. When the price of oil is high, revenues are strong and the government can afford to spend that money on public housing, health care subsidies and public education. Problems first started in 2014, when partially due to slower global growth and the fracking-revolution in the United States, the oil price came crashing down, and with it, the Venezuelan government revenues. As Venezuela’s oil revenues fell off a cliff, the value of the Venezuelan bolivar started dropping. Since the government had fixed the exchange rate of the Bolivar to the US dollar during the boom years; inflation soared to over 800% in late 2016. As a result, imports froze up and widespread shortages of basic needs, such a medical supplies and food, became an everyday reality. The Venezuelans have found themselves without any economic prospects and struggling to survive. The economic malaise translated into a massive defeat for the ruling Maduro government in the 2015 elections, where 2/3rd of the seats in parliament were won by the opposition. The Maduro-aligned Supreme Court promptly responded by declaring the elections invalid, inciting the current political crisis. Meanwhile, the Venezuelan currency has become increasingly worthless with purchasing power parity in 2015 dropping by roughly a tenth of its value since 2014, and the trend has only gotten worse in 2016 and onwards. A controversial election for a constituent assembly was held on July 30th and has been heavily contested. Numerous violent clashes occurred killing several, including a candidate for the assembly. The Maduro government claims a 41.5% turnout, while the opposition claims 88% abstained. The election has drawn widespread international condemnation, including sanctions by the U.S. government. The hope for any political solution is fast fading as increasing military crackdowns are further polarizing the country. Barring massive and painful economic reforms and a simultaneous break of political deadlock, Venezuela’s prospects are growing dimmer by the day and it is expected to remain a high scoring country on the political violence risk assessment. |

The price paid for South Sudan’s independence has been multiple longstanding, bloody wars with vast amounts of civilians fleeing or falling victim to hostilities. The country has fallen back into open conflict over the past years. Its effects could prove disastrous for the people of the country and region as a whole, as refugees add to the destabilization.

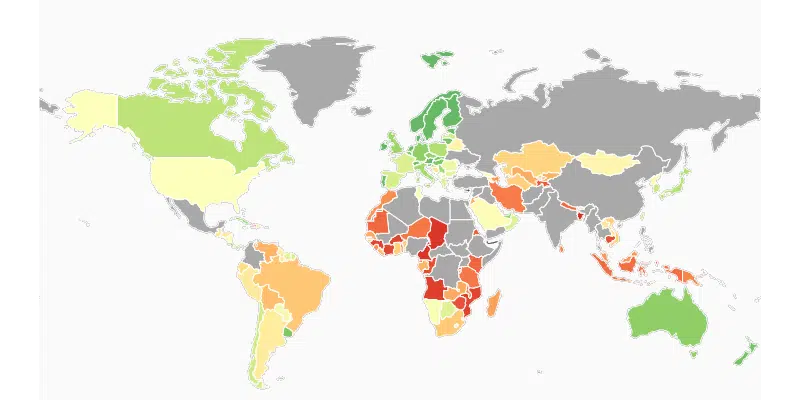

Conditions for civil wars can accumulate over time and erupt into sudden warfare. This monitor measures the extent to which countries are vulnerable to such ignitions, either rooted in political or socioeconomic tensions, increasing the risk of a full blown civil war. A number of models with different approaches that use various combinations of indicators from political, social, economic and environmental domains provide for a uniform risk assessment for the next 12 months.

These countries tend to have poor socioeconomic metrics across the board, ranking near the bottom in terms of health and life expectancy. Barring Mozambique, every country has at least one neighbor that is currently experiencing civil war and violence. Chad, Cameroon, Angola and the Republic of Congo lie to the west of the highly volatile region stretching from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Libya. Guinea, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire and Bangladesh have various Islamist extremist groups active in the region, further destabilizing their situations.

Cambodia and Mozambique fall into a different category. Both countries have fought extensive civil wars in the past that have left devastating legacies. The Khmer Rouge regime presided over the Cambodian genocide which killed an estimated 1.5 to 3 million Cambodians and, since it specifically targeted the higher educated, had severe consequences for the nation’s ability to rebuild after the war. Mozambique saw a civil war that lasted for 15 years and left the country littered with landmines. Mozambique has seen contested elections in 2014 flare up tensions between various factions, while Cambodia’s election in 2017 was preceded by increasingly authoritarian rhetoric from its prime minister Hun Sen.

Because event data is not used in the long term projection (as it is in the short term civil war risk assessment), there are sizable differences between the risk measured; the largest difference is in Mozambique. Mozambique’s long term risk for civil war, compounded by the country’s structural problems, is 96. Meanwhile in terms of civil war risk in the short term, it is only on the 32nd percentile in the world. Burkina Faso and Chad experience a similar trend, whereas the opposite is true for Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, both of which experience a risk factor in the short term that is significantly higher than in the long term.

Outlook

Most of these countries are vulnerable to spillover of conflicts from neighboring countries. A proactive stance to put international pressure on neighboring countries to end the violence would go a long way towards improving regional stability in the long run. Adequately tackling the threat of Islamist extremists might prove to be more viable in the short run as they do not require as much international coordination. Achieving either one of these goals would be a clear sign that these countries are willing and able to improve their lot.

For more information regarding methodology, click here.

| Close up: Bangladesh bound for trouble?

The combination of deep-seated socioeconomic, political and ethno-religious division along with the significant structural problems that Bangladesh faces make this country number one in terms of civil war risk in both short- and long-term. One of the most densely populated countries in the world with a population of over 150 million people, Bangladesh has to cope with intense demands on its infrastructure. While enjoying strong growth rates upwards of 5% and large positive trends, socioeconomic metrics are still poor across the board, especially in terms of literacy, sanitation and public health. Additionally, Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world in terms of climate change, situated in the delta of both the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers and suffering from regular floods in large parts of the country. Bangladesh’s political situation is volatile and unstable. During the 2014 election, all opposition parties boycotted the election in response to the government refusing to put into place a neutral caretaker government during the election meant to prevent manipulation of the vote. Over 50% of the seats in parliament were uncontested and voter turnout dropped from 86% in 2008 to a mere 50%. Violence and early closure of polling stations was rife and 21 people were killed on election day. In addition, the government has been accused of using its power to crack down on the media and intellectuals, including arbitrarily arresting prominent writers and journalists. Making matters worse, there has been a rise in Islamist extremist activity in Bangladesh: July 1st, 2016 saw an attack on a popular expat restaurant killing 22 people, including 18 foreigners. There have been indications that the attacks were executed with the involvement of ISIS or al-Qaeda, although the government has denied this. The myriad of challenges Bangladesh faces will require long term planning to rectify. A first step toward a solution would be a return to political order by holding snap elections. Such a move seems unlikely however, as the government has chosen its lot by pandering to Islamist extremists and shutting down criticism of its government. Bangladesh’s high economic growth rate might provide some relief if the country chooses to invest in its infrastructure and public health. Climate change is a looming problem that will require substantial foreign investment to manage. Failure to adequately plan for its consequences could lead to major food shortages, increasing social unrest and major refugee flows in the region. |

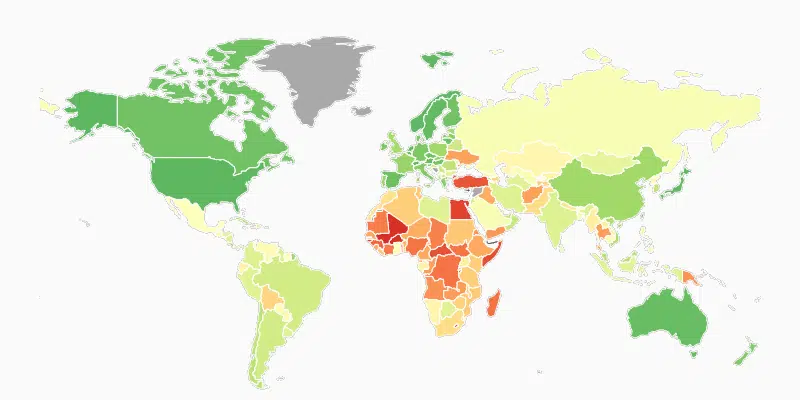

Coup d’etats have the potential to completely overthrow a status quo or regime over the course of a single night. The coup attempt in July 2016 in Turkey is a vivid reminder that these events are not a thing of the past, even if they have become rarer, with the annual occurrence having come down from double digits for most of the Cold War period to fewer than five in the last decade. It is worth noting that not all coups are military in nature, a coup could also be executed by a political elite. Either way, coups are by their nature sudden and potentially violent events, meaning that assessing the risk of their occurrence is not easy. Our assessment, which is based on well-regarded structural models, is shown below.

One of the highest risk factors in evaluating the risk of a coup is whether an attempt has taken place within the last 5 years. Besides Somalia and Guinea, at least one coup d’etat attempt has taken place within the last five years for every country in the top 10. For Guinea, a coup took place in 2008. Socioeconomic metrics factor in as well, with all countries having poor indicators overall in terms of their GDP growth rates and infant mortality. In addition, all of these countries have been subject to multiple radical shifts in government, with Burkina Faso experiencing 11 separate coups since gaining independence in 1966. Despite the overall turbulent history of these countries, only Mali, Egypt, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Turkey are currently experiencing spillover effects from conflicts in the region or qualify as post-conflict countries. Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho and Burundi have seen a total of 18 coup attempts between them since 1960, reflecting the notion that the strongest indicator of a future coup is a history of coup attempts.

Outlook

Coups are inherently difficult to predict as they often rely on schemes and collusions that are hidden from the public view. While it is certainly true that the overall political (in)stability of a country is related to the risk of a coup taking place, the exact nature of the coup can vary and depends on variables that are difficult to quantify. The degree of overall militarization in society, the level of control politicians have over military institutions, the political allegiance of army personnel at different levels of the army hierarchy, could all affect how, why and if a coup will take place. The countries that we have flagged as high risk are those that generally suffer from political instability as well as a history of coups. In some cases so many coups have taken place that they become a part of the overall political culture.

For more information regarding methodology, click here.

| Close-up: Post 2016 – Coup Attempt Turkey

On July 17th 2016, tanks rolled over the Bosphorus bridge, signalling an attempt by the military to overthrow the Erdogan government. Turkey is by far the largest economy on the top 10 ranking for the coup d’etat risk assessment and the only member of NATO identified of having such high risk. The high risk of a coup in Turkey as indicated by our monitor has to be put in the context of broader domestic and international challenges Turkey faces. Modern Turkish history is punctuated by successful coups in 1960, 1971, 1980 and 1997. The military has traditionally taken the role of guardian of the constitution and has intervened when it felt that Turkey’s secular roots were under threat. Despite the recent coup attempt, the current risk of a coup attempt in Turkey is considerably lower than it has been in the past. The rise after 2016 is partially attributable to the fact that recent coups are identified as a risk factor. In addition, the widespread reforms or crackdowns in the wake of the coup have contributed to political instability. Despite the July 2016 coup attempt, the overall risk of coup attempts both globally and in Turkey specifically has gone down. The direct effects and consequences of the July 2016 coup attempt are evolving to this day, but there are clear trends visible already. The first is the large number of civil servants and teachers that were purged. In addition, over 100 news outlets were closed and 81 journalists were shuttered and jailed, giving 2016 the highest number of journalists imprisoned since 1990. These developments could reduce overall bureaucratic competence and public accountability of politicians, and potentially worsen Turkey’s political vulnerability to political violence in the long term. The image that the coup and terrorist attacks have created abroad has caused a decline in tourism and foreign directed investment, causing budget strains. The second trend is that following Erdogan’s constitutional referendum victory, the prospects of Turkey transitioning from a parliamentary democracy towards a presidential republic could create further instability. At the same time, research from Kadir Has University has indicated that consumer confidence, public trust in the military and public approval of extending the state of emergency are falling. The Turkish government’s ability to manage the economic slowdown while simultaneously being responsive to the demands of the Turkish people will either deter or spur future political violence. At the same time, Turkey’s policy of ‘zero neighbors with problems’ has deteriorated into ‘zero neighbors without problems’. Turkey’s relations with various great powers have become strained: faltering EU accession talks, increasingly uneasy relations with NATO allies such as Germany and complicated interactions with other countries vis-a-vis the Syrian conflict. The possible scenarios for Turkey on an international level are further examined in this report. |

Over the past two years, Yemen has suffered a devastating civil war. Its consequences have been catastrophic, with famine and disease ravaging the population in addition to casualties from the open hostilities. The risk assessment for state-led killing is based on deliberate actions by state agents which results in over 1,000 non-combatant deaths in their country in an annual time frame. A single ongoing state-led mass killing does not guarantee that another episode would not break out, hence we also assess the risks in countries already affected by this type of political violence. The first signs or even risk of state-led mass killings should raise the gravest concerns and immediate reaction from the international community.

With every county in the list currently experiencing conflict, it is clear that state led mass killings do not come out of nowhere. Large racial minorities that are economically or politically disenfranchised are a recurring theme throughout these countries. In particular in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia and Sudan, the high risk factor is amplified by a large number of different ethnicities being forced together through the arbitrary borders drawn during the colonial era. Ongoing or recent conflicts further compound those problems; Boko Haram threatens the northeast of Nigeria, both Somalia and Sudan have seen multiple civil wars, and the DRC was at the the center of what has been referred to as the African world war. As a result, the inhabitants of these countries have vivid memories of ethnic cleansings, either as a victim or as the perpetrator.

Another set of countries, namely Libya and Egypt, have been characterized by much stronger central governments that have either been overthrown, challenged or severely disrupted. In Libya, the downfall of Gaddafi enabled different groups to overrun government armories, gaining access to heavy weaponry. Egypt has seen numerous governments since the fall of Mubarak with widespread political repression. Turkey is still dealing with the effects of the coup and is going through a purge of its civil service, journalistic and educational institutions. Simultaneously, major constitutional reform has been passed that strengthens the power of the executive branch considerably.

In Pakistan and Myanmar, the risk of the onset of state-led mass killings is largely rooted in religion. Pakistan has a long history of clashes with India that are remnants from the the partition of India in 1947, and the Hindu minority in Pakistan has been subject to persecution. Tensions flared in September 2016 as several skirmishes occurred along the line of control in the Kashmir region; small scale hostilities are ongoing. In Myanmar, there have been several crackdowns on the Rohingya minority that have led to accusations of crimes against humanity. Finally, the risk in Yemen is heightened due to the deteriorating conditions in the ongoing civil war. There is widespread famine and disease as the conflict between the coastal elite and mountainous tribes continues.

Outlook

The risk of the onset of state led killings is highest in some of the most troubled countries on earth. The fact that all these countries currently experience violent conflict bodes ill for their long term prospects. Careful mediation between the ethnic or religious groups might offer some relief, but in some cases the tensions are too deeply ingrained in history. Even if relations between the groups would improve, there are still major economic challenges and inequalities that could eventually reignite the long standing feuds. Significant efforts must be made both domestically and internationally to ensure that these countries are given the adequate means and information to avoid a return to genocide.

For more information regarding methodology, click here.

| Close-up: Libya: The shifting balance of power

Since the fall of Colonel Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has experienced violent clashes between warring factions. Libya’s high ranking on the risk assessment for the concept of state-led mass killings has to be put in the volatile and complex domestic political context it is currently dealing with. The power vacuum left in Libya and the MENA region generally has been filled with a variety of groups, including Islamist extremists. Control of Libya has seesawed between parliaments based in Tripoli and Tobruk. In 2016, a Tunisian based, UN backed government was appointed, although both Tripoli and Tobruk refused to acknowledge its authority. Peace talks held in Paris on July 25th of this year have led to a ceasefire and the goal of holding elections as early as 2018. The peace talks were held between the two main factions in Libya, the Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA), while ignoring the numerous smaller factions/militias that roam across Libya. Besides the LNA and GNA, numerous factions are vying for influence. The Islamic State, while defeated in Benghazi, continues to disrupt the GNA. Led by prime minister Fayez al-Sarraj, the GNA has the backing of NATO, Israel and the United Nations as a whole. The LNA, led by General Khalifa Haftar, has been the main beneficiary of the Paris talks. Controlling vast swaths of land in the east of Libya, Haftar has taken control of the major oil producing ports and facilities to the south of Benghazi. As it stands, Haftar controls a majority of land, oil and armed forces in Libya while simultaneously being popular among the citizens of Libya, paving a possible presidential run in 2018. With the waxing control of Haftar, it is looking increasingly likely that he will end up controlling Libya in the short term. His position is the strongest both economically and militarily. The onset of political violence in Libya is rooted in the current fragile and highly complex situation and while a tentative ceasefire has been established, any escalation could come at disastrous cost for the civilian population who might find themselves caught in the middle. |

The wealth of data that is out there and will continue to be generated and updated could help shape better foreign policy and has the potential to transform foreign and security policy in the 21st century, helping to minimize the detrimental effects of political violence on a global scale. Early warning allows for early, bespoke action that reduces the impacts of political violence, the cost of intervention, and most importantly, minimizes the human cost of conflicts. For that purpose, the monitors track the risks of different types of violence, civil war, state-led killings and coup d’etats, based on a number of different theoretical assumptions, methodological approaches and data sources. When looking at the four monitored types of violence, a few countries score high on more than one monitor. This is attributable to the fact that the different forms of violence emanate from overall political instability, and further research on their commonalities is needed. Tracking ongoing events for timely risk assessment is currently only used for the short term civil war monitor. Developing this capability for other types of political violence is feasible, but would require further resources.

Leveraging analytic capabilities

The field of data-driven conflict analysis can provide more comprehensive and actionable information than was previously available and possible. The process of using model frames and monitors are imperative to the debate on how we understand and assess the risks of political violence. As more salient data is fed into the models, the risk assessments will become increasingly precise. The intersection of data analytics and deep subject matter expertise will empower diplomats and policymakers to respond to a threat landscape that can change quickly. Giving decision- and policymakers the information they need to make decisions and the tools to track the effects of those decisions is vital in minimizing the onset and the effects of political violence.

Must reads

Short Read Excerpt: Deadly Conflicts – Council on Foreign Relations

Short Read Early warning system flags global financial crises – University of Birmingham

Short Read The Graveyard of Empires and Big Data – Foreign Policy

Long Read Forecasting civil conflict along the shared socioeconomic pathways – Uppsala University

Long Read Seizing the Moment: From Early Warning to Early Action – Crisis Group

Long Read Early ViEWS: A prototype for a political Violence Early-Warning System – Uppsala University

Methodological Notes

There is a rich and diverse field of research dedicated to assessing the risks of political violence, and the models presented here are only some of many possible formulations. The exact set of metrics chosen reflect a broader conceptualization of what political violence constitutes. Much of the research done in this field since the turn of the century and until the last few years has been based on annual, structural models that are sparsely updated, or have a purely qualitative focus. In the last few years, more granular and timely data is increasingly available, and as such, one of our models has a shorter timeframe.

Namely, while the risk assessments for coup d’etats and state-led mass killings are made on an annual basis, we utilize two distinct models for civil wars. The first includes event data in the short term, and the second is a composite of some of the most well-regarded structural models in conflict literature, with up-to-date data. Within the HCSS civil war models, countries that are currently experiencing conflict are typically not considered. This is due to the fact that the considerations involved in assessing the risks of the onset of political violence episodes are different from those involved in tracking ongoing conflicts.

The next substantive step in our research would be to build models that assess the risks of political violence on a sub-national level. On that front, tracking and visualizing ongoing conflicts based on exact location is already straightforward, and will be included in the second political violence alert in the winter of this year. Assessing the risks on a very granular basis, however, would need substantial time investment. More resources would also be needed to expand the list of political violence and conflict types for which we have models. For example, terrorism, intrastate disputes and non-state violence are not included per se, though there are some overlaps with the types of violence included in the current portfolio.

Non-State Mass Killings

The state-led mass killings monitor does not include data or information on non-state mass killings. Since non-state mass killings are a relatively new occurrence, they are, as of yet, not included in this model. Future iterations that capture this new dynamic aspect of political violence are currently being developed. However, the risk assessment of state-led mass killings makes use of machine learning that utilizes historical data, since historically most mass killings have been conducted by states, our conceptual understanding of state-led mass killings is far deeper and more reliable.

Comparative table

The table below shows the fundamental methodological characteristics of the four frameworks. The following aspects are shown:

- Conceptualization and inclusion criteria: How is the type of political violence defined and what is the minimum level of violence needed for inclusion?

- Predictors: what kind of variables were used in statistical models to assess the risks of violence? Here only their type is mentioned, for in-depth overview, refer to the methodological documentation.

- Model: What kind of statistical model was used?

- Data split: How was data split between training set (to fit the models) and test set (to test the predictive power of model). For some models, a temporal split was used; for others, cross-validation was used instead.

- Temporal Aggregation: What was the aggregation level regards to time? Currently the models use either annual data only or in combination with monthly data

- Read more: As the current table only describes the basics, we also provide links to more in-depth descriptions of the frameworks.

| Metric | Civil War (short) | Civil war (long) | Coup d’etat | State-led mass killings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization and inclusion criteria | Both ethnic and revolutionary civil wars are included (see here for definitons). For inclusion, more than 1,000 individuals have to be mobilized by at least two parties, more than 1,000 casualities must occur over the course of the conflict, with more than 100 deaths in a single year. | Different by models (see full documentation). | Forceful seizure of national political authority by military or political insiders | The actions of state agents result in the intentional death of at least 1,000 noncombatants from a discrete group in a period of sustained violence. |

| Predictors | Both structural indicators (regime type, infant mortality etc) on annual basis, as well as dynamic indicators based on event data on monthly basis | Various structural indicator combinatons, different by models | Structural indicators, different by models | Structural indicators, different by models |

| Model | Logistic regression | 4 logistic regression models, aggregated | Logistic regression, complementary log-log, and random forest models, aggregated | Logistic regression and random forest, aggregated |

| Training / test split | Training: 1979-1999; Test: 2000-… | Different by models | 10-fold cross-validation / Training: 1950-1975; Testing; 1976-… | 10-fold cross-validation |

| Temporal aggregation | Monthly | Annual | Annual / monthly | Annual |

| Read more | Link | Link | Link 1 and Link 2 | Link |

Authors: Hannes Roos, Karlijn Jans, Paul Verhagen

Contributors: Tim Sweijs, Mateus Mendonça Oliveira

About Monthly Alerts

In order to remain on top of the rapid changes ongoing in the international environment, the Strategic Monitor of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence provides analysis of global trends and risks. The Monthly Alerts offer an integrated perspective on key challenges in the future security environment of the Netherlands along the following four themes:

- Vital European and Dutch Security Interests

- New Security Threats and Opportunities

- Political Violence

- The Changing International Order

The Monthly Alerts reflect the monitoring framework of the Annual Strategic Monitor report, which is due for publication in January 2018. Each Monthly Alert offers a selection of discussions of emerging developments by key stakeholders in publications from governments, international institutions, think tanks, academic outlets and expert blogs, supported by previews of ongoing monitoring efforts of HCSS and Clingendael. The Monthly Alerts run on a four-month cycle alternating between the four themes.

Disclaimer

This Report has been commissioned by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence within the PROGRESS framework agreement, lot 5, 2017. Responsibility for the contents and for the opinions expressed rests solely with the authors; publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defence.