Research

Environmental resources and related infrastructure have long been used as both an instrument and strategy of military conflict and terrorism. However, due to global trends, the unlawful use of environmental resources or systems to function as both a target and an instrument of armed conflict is growing in frequency and efficiency. In this snapshot, assistant analyst Femke Remmits and strategic analyst Bianca Torossian shed light on the risk environmental terrorism poses in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Introduction

Terrorist organizations commonly use a range of conventional and non-conventional measures to attack, coerce, intimidate, and/or weaken their opponent. Among the tactics adopted by terrorist groups is the use of the environment and its resources as either a target or a weapon of conflict. Between 2014 and 2017 the Islamic State (IS) engaged in various attacks on the Iraqi and Syrian energy sectors, confiscating and destroying significant oil and gas fields. This strategy has also been used by Al Qaeda. In 2014 and 2015, IS captured large dams at Falluja, Mosul, Samarra, and Ramadi as part of a wider strategy to flood surrounding towns or disrupt critical water supplies to local communities.

The targeting of environmental resources and related infrastructure has long been used as both an instrument and strategy in conflict and is addressed by various international humanitarian laws. Among these are The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the 1949 Fourth Geneva Conventions, the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Convention (Protocol I and II), the 1976 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD) and the 1982 World Charter for Nature. These international laws or agreements explicitly prohibit the intentional or indiscriminate destruction of the environment, its resources and vital civilian infrastructure, particularly when the damage is highly disproportionate to military necessity.

Though environmental terrorism is not a new phenomenon, it is growing into an increasingly serious threat. Today, climate change, demographic trends and environmental degradation increasingly pressure the availability of essential resources, such as food, water, and energy. These trends increase the strategic importance of vital human resources. As a result, the unlawful use of environmental resources or systems as both a target and an instrument of armed conflict is growing in frequency and effectiveness. This tactic – also termed environmental terrorism – aims to inflict damage on individuals and/or to deny communities environmental value(s). This snapshot discusses the risk of the use of environmental resources and related infrastructure by terrorist actors in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), highlighting the security threat of environmental terrorism.

Assessing the Threat of Environmental Terrorism in the MENA Region

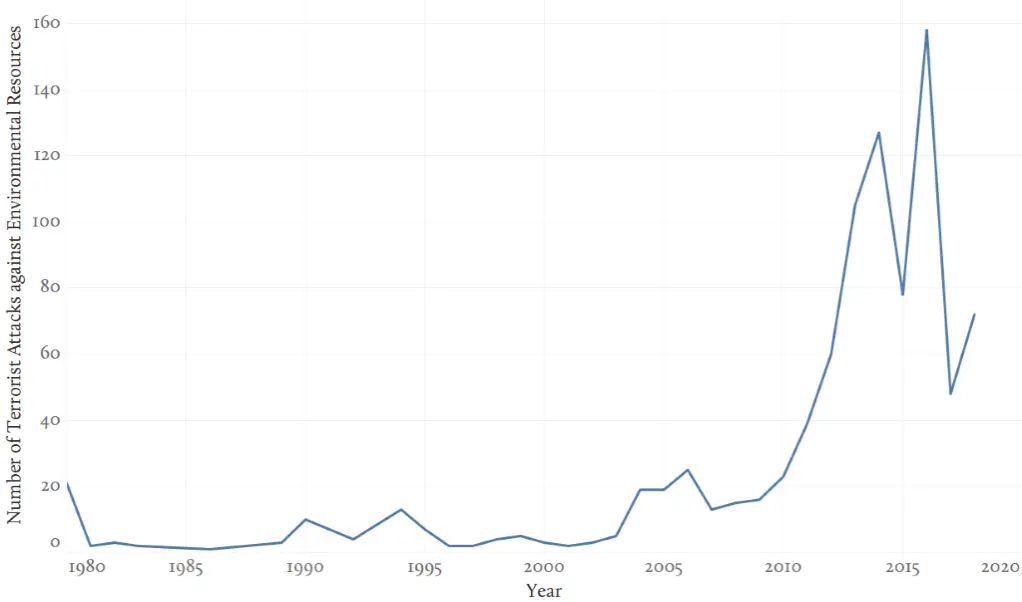

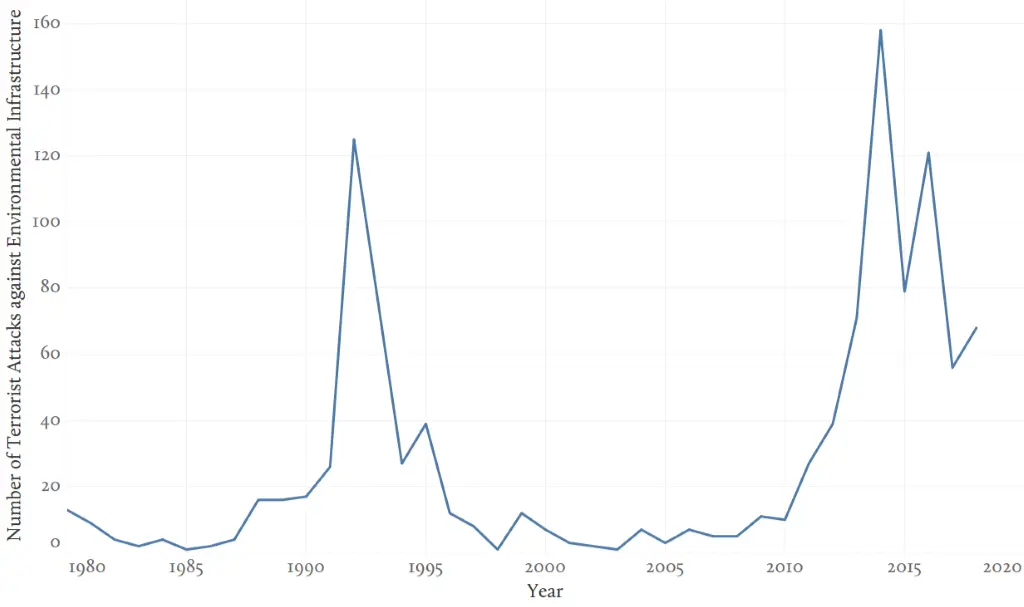

Based on an analysis of data from the START Global Terrorism Database, there is an increasing trend in the MENA region (Figure 1) in the use of the environment and its resources as either a target or a weapon. Since 1980, there has been a significant rise in the number of terrorist attacks against environmental resources – including water, food, and energy utilities – or related infrastructure – such as power plants, oil and gas infrastructure, water-related infrastructure, agricultural or crop land – as a tactic of war with a considerable peak between 2013-2016 (see Figure 2 and 3).

The rising trend between 2013-2016 is in part due to the upsurge in overall attacks by terrorist actors during the civil wars in Yemen and Libya as well as the initial territorial expansion (and subsequent drawback based on scorched-earth tactics) of IS in Iraq and Syria. The targeting of environmental infrastructures also shows an increase in 1992, which can partially be explained by the targeted attacks of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) on oil facilities in Turkey that year after intensified clashes with Turkish state forces. Although trends in environmental terrorism are to some extent linked to a general upward trend in terrorist activity, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that the use of environmental resources and related infrastructures are increasingly a target of terrorist groups operating in the MENA region.

To evaluate the threat of these tactics in more detail, the next sections focus on the manipulation of water-related resources in the MENA region. The potential intent that terrorist actors operating in MENA countries might have for employing water-related resources as an instrument or a tactic is discussed relative to the capability actors enjoy for doing so. While intent pertains to why and to what purpose terrorist groups in the MENA region would employ environmental resources, capabilities refer to the characteristics of the environment in which terrorist groups operate that make the context ripe for the adoption and implementation of these tactics. The last part of this section focuses on instances of environmental terrorism targeting water resources in countries of the MENA region.

Intent of Environmental Terrorism

Water-related resources can be used as both a weapon and tactic of conflict to further an actor’s ideological and strategic goals. The question of why and to what purpose terrorist actors use water resources and related infrastructures can in part be explained by the arsenal of weapons and strategies available to such actors. Terrorist organizations commonly have access to limited material and/or financial resources to effectively fight with. To compensate for this lack of strong military power, terrorist organizations employ a variety of means and strategies to target their opponent. The purpose of using the environment – and water resources and infrastructure specifically – as a tactic can be described along several motives:

- Psychological motives: the potential to generate public fear and anxiety, and to weaken public confidence in state authorities;

- Organizational motives: strengthen local legitimacy and authority in the face of opponent’s position (often national governments or other non-state armed groups);

- Operational and instrumental motives: using increased livelihood insecurity and scarcity in resources as a means of recruitment and employing the destruction and control of scarce environmental resources as a weapon of war.

Capability of Environmental Terrorism

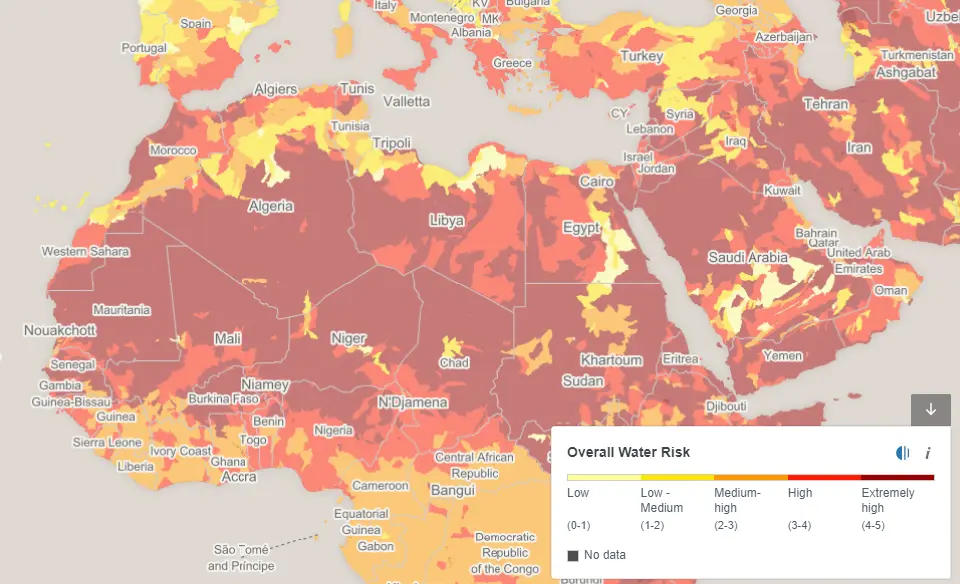

Whether terrorist groups operating in the MENA region are able to adopt and implement water-related resources as tactics of conflict is largely determined by both the availability and quality of this environmental resource as well as factors and mechanisms that shape the sensitivity, and thereby the potential, of it to be employed as an instrument of conflict. Several conditions make the MENA region particularly susceptible and suitable for the adoption of these tactics. First, the countries that comprise the MENA region have arid climates and the availability and quality of water resources is extremely critical. The Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas of the World Resources Institute (WRI) measures overall water risk based on all water-related risks, by aggregating all indicators that pertain to the physical quantity, physical quality, and regulatory and reputational risks of water resources. Figure 4 below shows high levels of water risk across the MENA region. Second, significant shares of their populations rely on the region’s major water sources for home water supply, but these same sources are also relied upon for energy production, agriculture, and livestock farming. Economic reliance on these sectors implies that changes in the availability and quality of environmental resources, like water, can severely impact livelihood and food security.

Third, state instability, weak institutions and corruption restrict the ability of governments to deliver basic services, manage critical environmental resources, enforce resource rights, resolve competition over resources, and limit illegal connections to power lines and the construction of illegal wells. As indicated by the Fragile States Index by the Fund For Peace, these challenges are widespread across MENA countries.

Instances of Environmental Terrorism

The map below (see Figure 5) shows water-related conflict incidents by both non-state as well as state actors in the past ten years. Examples include IS targeting (confiscating or destroying) of water infrastructures, water supplies, energy infrastructure (including oil production and refining installations) agricultural fields in Iraq and Syria. In 2013, IS confiscated the Tabqa al-Thawrah dam in Syria, the largest hydroelectric dam in the country, in addition to many other national dams, canals, and water reservoirs. In April 2014, IS administered control over the Falluja Dam in Iraq in order to flood large areas of land below the dam, including over 10,000 houses and 200 square kilometers of productive farm and cropland. This resulted in the displacement of 60,000 Iraqis. In December 2014, IS polluted drinking water supplies with crude oil throughout Iraq. In May 2015, the group seized the Ramadi Dam and partially closed its gates, causing an increased flow of water from the Euphrates into Habaniyah Lake and temporarily reducing the water flow of the Euphrates River in Iraq to 50 percent of normal capacity. This critically limited the supply of water to irrigation systems and treatment plants in the provinces of Babil, Karbala, Najaf, and Qadisiya and caused severe, widespread food insecurity across Iraq. In addition, IS used its control of the dam to lower water levels of the Euphrates River beneath the dam, allowing IS troops to cross the river and attack Iraqi troops at the opposite bank before continuing its advance towards the city of Ramadi.

Terrorist organizations like IS and Boko Haram have targeted the environment and its resources in combination with other tactics to generate displacement as well as to facilitate control of and recruitment among local communities through the provision of livelihood and security in fragile contexts. Through these tactics, terrorist organizations seek to enhance their local authority and legitimacy, damage and undermine the opponent (in many cases the state) and to coerce populations by inflicting severe physical and economic damage to infrastructure and services, inducing widespread fear, and challenging the state’s legitimacy.

These are only some examples during which a terrorist group used crucial water resources or related infrastructure as a tactic to further its ideological and military objectives. In the Lake Chad region, where millions of people are dependent on the water of the lake, Boko Haram has manipulated food and water insecurity to challenge state authority and recruit among the local population. They do so by offering provision of vital resources, livelihoods, security or other material benefits to vulnerable populations in return for their support and services to the terrorist group. By taking over essential services traditionally falling under the responsibility of the state, Boko Haram seeks to increase its own authority and weaken the legitimacy of central governments among local populations. Apart from cutting off water supplies, other ways of using water as an instrument of war include flooding towns or poisoning critical water resources, which both IS and Boko Haram have done in recent years. A study by the UN observed that young Muslims in Africa are more likely to join extremist groups based on social grievances and a lack in confidence with the local government to provide essential services rather than out of religious motivation.

Conclusion

This snapshot briefly outlines how the use of environmental resources and related infrastructure by terrorist actors materializes in susceptible contexts. Though the utilization of this tactic is not a new phenomenon, its frequency and efficiency are posing an increasing threat. The transnational strategy, mixed tactics, coordinated operations, and brutal use of terror related to environmental terrorism are increasingly evident in the MENA-region. Addressing the use of environmental resources and related infrastructure as part of the wide arsenal of terrorist tactics is particularly of concern considering that climate change is projected to intensify resource scarcity and livelihood insecurity globally. To address environmental terrorism, it is first important that national security actors and institutions consider and integrate the strategic importance of critical resources and infrastructure in counter-terrorism approaches. Second, government authorities should more actively and powerfully condemn the use of water and related resources as a violation of international humanitarian law through international legal mechanisms. And third, national and subnational state institutions need to ensure adequate resource management and infrastructure to provide citizens with basic rights, including water, food, and livelihoods, to reduce the effectiveness of the destructive tactics underlying environmental terrorism.

Bibliography

Adelaja, Adesoji, Justin George, Takashi Miyahara, and Eva Penar. “Food Insecurity and Terrorism.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 41, no. 3 (2019): 475–97.

Andrew, Silke. Routledge Handbook Of Terrorism And Counterterrorism. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

Brozka, Michael. “Introduction: Criteria for Evaluating Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Security Sector Reform in Peace Support Operation.” International Peacekeeping 13, no. 1 (2006): 1–13.

Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate. “Physical Protection of Critical Infrastructure Against Terrorist Attacks.” New York: United Nations Security Council, 2017.

Crawford, Alec. “Climate Change and State Fragility in the Sahel.” Madrid: FRIDE, 2015.

Gleick, Peter H. “Water and Terrorism.” Water Policy 8, no. 6 (2006): 481–503.

———. “Water as a Weapon and Casualty of Conflict: Freshwater and International Humanitarian Law.” Water Resources Management 33 (2019): 1737–51.

Hentz, James J., and Hussein Solomon. Understanding Boko Haram: Terrorism and Insurgency in Africa. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

International Crisis Group. “The Central Sahel: Scene of New Climate Wars?” Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2020.

Jasper, Scott, and Scott Moreland. “The Islamic State Is a Hybrid Threat: Why Does That Matter?” Small Wars Journal. Accessed October 21, 2020. https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/the-islamic-state-is-a-hybrid-threat-why-does-that-matter.

Kalicki, Jan H. “2015 Global Energy Forum: Revolutionary Changes and Security Pathways.” Washington, D.C.: Wilson Center, 2015.

King, Marcus. “The Weaponization of Water in Syria and Iraq.” The Washington Quarterly 38 (2015): 153–69.

Kohler, Christina, Carlos Denner dos Santos, and Marcel Bursztyn. “Understanding Environmental Terrorism in Times of Climate Change: Implications for Asylum Seekers in Germany.” Research in Globalization 1 (2019): 1–8.

Koubi, Vally, Gabriele Spilker, Tobias Böhmelt, and Thomas Bernauer. “Do Natural Resources Matter for Interstate and Intrastate Armed Conflict?” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 2 (2013): 227–43.

Lossow, Tobias von. “The Rebirth of Water as a Weapon: IS in Syria and Iraq.” The International Spectator 51, no. 3 (2016): 82–99.

———. “Water as Weapon: IS on the Euphrates and Tigris. The Systematic Instrumentalisation of Water Entails Conflicting IS Objectives.” Stiftung Wïssenschaft Und Politik, SWP Comments 3, 2016, 8.

Minorities at Risk Project. “Chronology for Kurds in Turkey.” Refworld, 2004. https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f38e91e.html.

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. “Global Terrorism Database (GTD).” START – National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2020.

Nett, Katharina, and Lukas Rüttinger. “Insurgency, Terrorism and Organised Crime in a Warming Climate: Analysing the Links Between Climate Change and Non-State Armed Groups.” Berlin: Adelphi, 2016.

Pacific Institute. “Water Conflict Chronology.” The World’s Water, 2020. http://www.worldwater.org/conflict/map/.

Paskalev, Kliment. “The Changing Character of War – Hybrid Warfare in the 21st Century.” Accessed May 8, 2020. https://www.academia.edu/39264840/The_changing_character_of_war_-_Hybrid_Warfare_in_the_21st_century.

Piesse, Mervyn. “Boko Haram: Exacerbating and Benefiting From Food and Water Insecurity in the Lake Chad Basin.” Dalkeith: Future Directions International, 2017.

Schwartzstein, Peter. “Climate Change and Water Woes Drove ISIS Recruiting in Iraq.” National Geographic News, November 14, 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/11/climate-change-drought-drove-isis-terrorist-recruiting-iraq/.

Sowers, Jeannie L., Erika Weinthal, and Neda Zawahri. “Targeting Environmental Infrastructures, International Law, and Civilians in the New Middle Eastern Wars.” Security Dialogue 48, no. 5 (2017): 410–30.

The Fund for Peace. “Fragile States Index Annual Report 2020.” Washington, D.C.: The Fund for Peace, 2020. https://fragilestatesindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/fsi2020-report.pdf.

The World Bank. “Iraq: Reconstruction and Investment – Part 2: Damage and Needs Assessment of Affected Governorates.” Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2018.

United Nations Development Programme, and Regional Bureau for Africa. “Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives and the Tipping Point for Recruitment.” New York: United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Africa, 2017. http://journey-to-extremism.undp.org/content/downloads/UNDP-JourneyToExtremism-report-2017-english.pdf.

Wilgenburg, Wladimir van. “ISIS Burns Crop Fields in Iraq’s Disputed Makhmour: Peshmerga Commander.” Kurdistan24, May 12, 2020. https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/e4fb3cc2-127e-4916-a458-a07338eb1bbf.