In a joint statement issued last week, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) signaled the expansion of its focus to Asia as it seeks to respond to the rise of China as an economic and military power.

Observers have keyed in on the communique’s direct comments on China: It describes Beijing as posing “systemic challenges” to the global order, as opposed to being a “threat” like Russia, while leaving the door open for cooperation on issues like climate change.

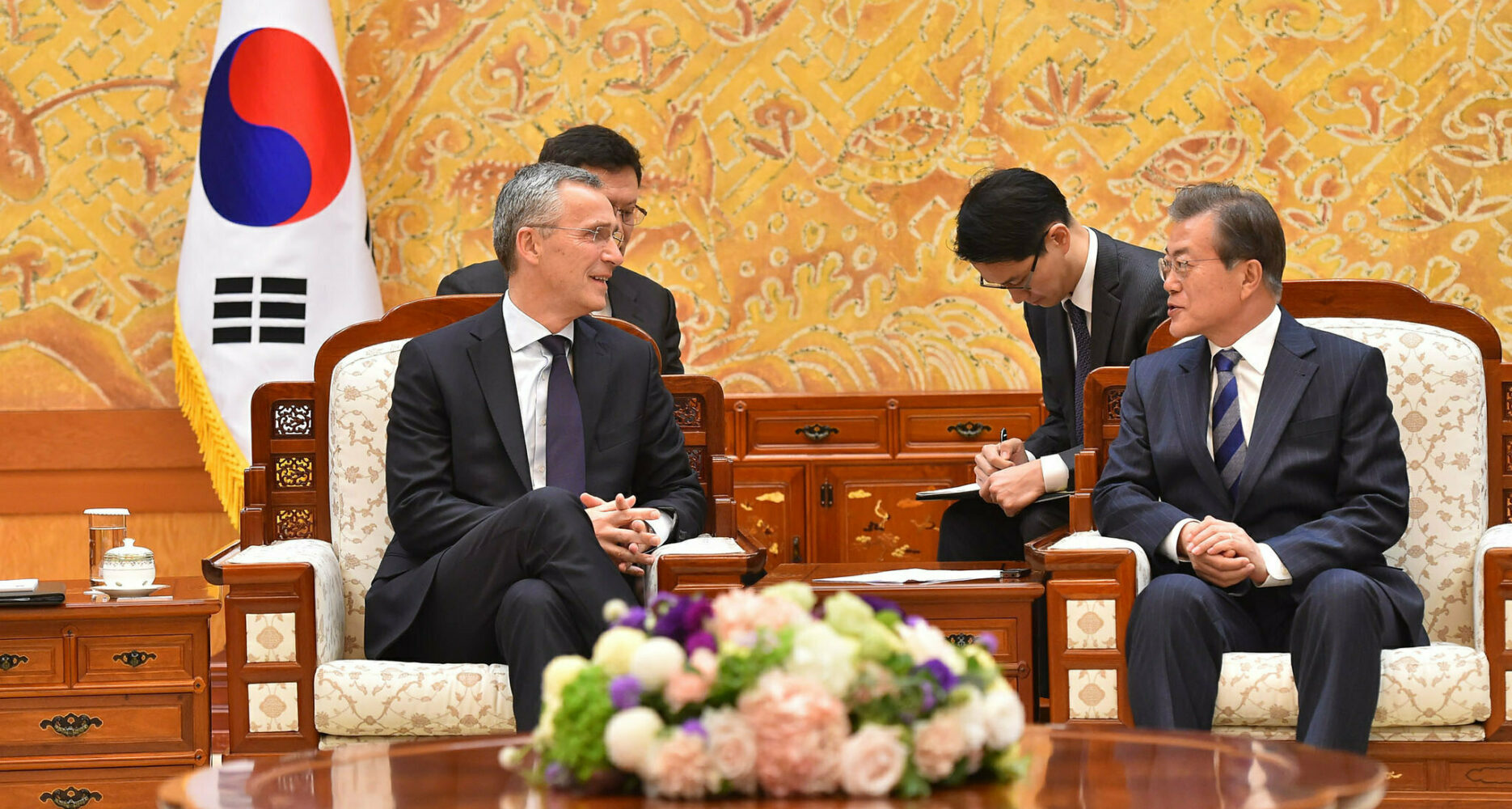

But the joint statement also makes clear that NATO’s interest in Asia goes beyond just relations with China, as it states the alliance is enhancing cooperation with established partners in the region, including South Korea, and calls for the complete denuclearization of North Korea.

Taken together, the language in the communique raises questions about what role the security institution historically focused on Europe might play half a world away in Asia, and how NATO’s approach might impact the geopolitical situation on the Korean Peninsula.

Experts told NK News that NATO has so far only mapped out the broad contours of its strategy in the Indo-Pacific, but that the joint statement represents an agreement among the 30 member states to discuss China and the Indo-Pacific more going forward.

Seoul, they said, is likely to welcome NATO’s presence but will be wary of cooperation that appears anti-China. They added that the alliance is unlikely to directly participate in North Korea denuclearization efforts, though it remains an issue of concern.

NATO’S AMBITIONS IN ASIA

NATO’s interest in Asia is not new. Member states like France and the U.K. have territories and longstanding ties in the region, and South Korea has worked with NATO since 2005.

But experts say the organization’s interest in the Indo-Pacific has accelerated in the past two to three years as Beijing has grown more militarily assertive — sailing naval vessels in the Arctic and conducting joint exercises with Russia in the Baltics — and as the security implications of economic ties with Beijing have become clearer.

Stephan Fruehling of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at Australian National University (ANU) noted that North Korea’s ability to reach Europe with its missiles has further underscored Asia’s relevance to NATO members.

“There is a realization that what’s happening in North Korea, and particularly in China, does directly influence the security situation in the North Atlantic area,” Fruehling told NK News.

He stressed that this does not mean NATO has ambitions to “go” to Asia and build up a military presence in the region. Instead, Fruehling said it’s likely NATO will increase political consultation on the Indo-Pacific and release statements on issues related to China.

Paul van Hooft, a senior strategic analyst at the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS), said that NATO military involvement in the Indo-Pacific would “be a bridge too far” and that European states have limited capability to project a military presence.

He said NATO, as a forum for political coordination as opposed to a strict military alliance, could do more to push back against Chinese economic influence and disinformation campaigns, including through the use of European diplomatic presence in the region.

Member states, Van Hooft said, could also make use of their ships in the Indo-Pacific to carry out “freedom of navigation” operations. These operations, which the U.S. and other nations have conducted, typically involve sailing through disputed waters to contest what they view as China’s “excessive maritime claims” in places like the South China Sea.

SOUTH KOREAN COOPERATION

NATO’s commitment to working more with its Asia-Pacific partners — Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea — could present a diplomatic challenge to Seoul as it seeks to navigate the growing great power struggle between its traditional ally the U.S. and its largest economic trading partner China.

Chung Kuyoun, an assistant professor of political science at Kangwon National University, said China will resist any NATO activity in Asia because it will see this as an effort to contain its movement toward the Pacific and beyond.

Chinese officials reacted sharply to the modulated description of China as a “challenge” in last week’s communique, labeling it a “continuation of the Cold War mentality and bloc politics.”

In part in consideration of its relations with Beijing, South Korea has been hesitant to participate in the informal Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, involving the U.S., Australia, India and Japan, though Seoul recently voiced support for such “regional multilateralism.”

Chung said Seoul will view NATO’s presence in Asia as a way to support the established international order.

“South Korea would welcome in principle any actions that support freedom of navigation and preserval of law but not necessarily exclude China or decouple great powers in the region,” she told NK News. “[South Korea] is taking a more nuanced approach toward great power competition at this moment.”

The specifics of concrete cooperation between South Korea and NATO will depend in large part on Seoul, according to Fruehling of ANU. He explained that NATO, under its partnership model, does not seek to define the objectives of cooperation, instead relying on its partners to indicate what they want from the alliance.

Fruehling said that, given the communique’s emphasis on air and missile defense, this could be a potential area for cooperation with South Korea, along with expert exchanges.

Chung also cited the possibility of working with NATO on cybersecurity, women’s empowerment issues and climate change, as well as economic and supply chain issues.

The experts agreed that NATO is unlikely to conduct military exercises with its partner countries in the Indo-Pacific, though Van Hooft of HCSS noted that freedom of navigation exercises do involve military vessels.

NORTH KOREA FACTOR

If and when North Korean denuclearization talks resume — which appears unlikely for the foreseeable future — NATO will likely remain on the outside looking in.

Fruehling said Britain and France, as U.N. Security Council members, may be more involved, but the participation of all of NATO would only make negotiations more difficult for the United States.

“That would just mean that they [the United States] don’t just have to deal with South Korea and Japan, but they have to deal with 30 European [states] at the same time,” he said.

Chung agreed, stating that North Korea only cares about talks with the United States.

She also downplayed the possibility that NATO action in the Indo-Pacific will drive China and the DPRK closer. Beijing, Chung said, “thinks of North Korea as a liability rather than an asset” with which it can align strategically against the United States.

Nevertheless, Van Hooft said there’s real concern in European capitals about how rising threats from China and Russia might drive new states to acquire nuclear weapons.

“So I think in that sense it is really understanding that dampening as much of the dynamics in North Korea is essential to at least try to take away another stressor on the nuclear order as it already exists,” he said.

Though North Korea’s nuclear weapons have not historically been a top agenda item for NATO, Van Hooft said global developments and regional dynamics, like the conflict between India and Pakistan, have created a potentially dangerous situation that will require new arms control and nonproliferation efforts.

“It takes a lot of work to quite literally not blow up,” he said.

This article by Arius Derr first appeared in NK News.