Research

Authors: Jilles van den Beukel & Lucia van Geuns

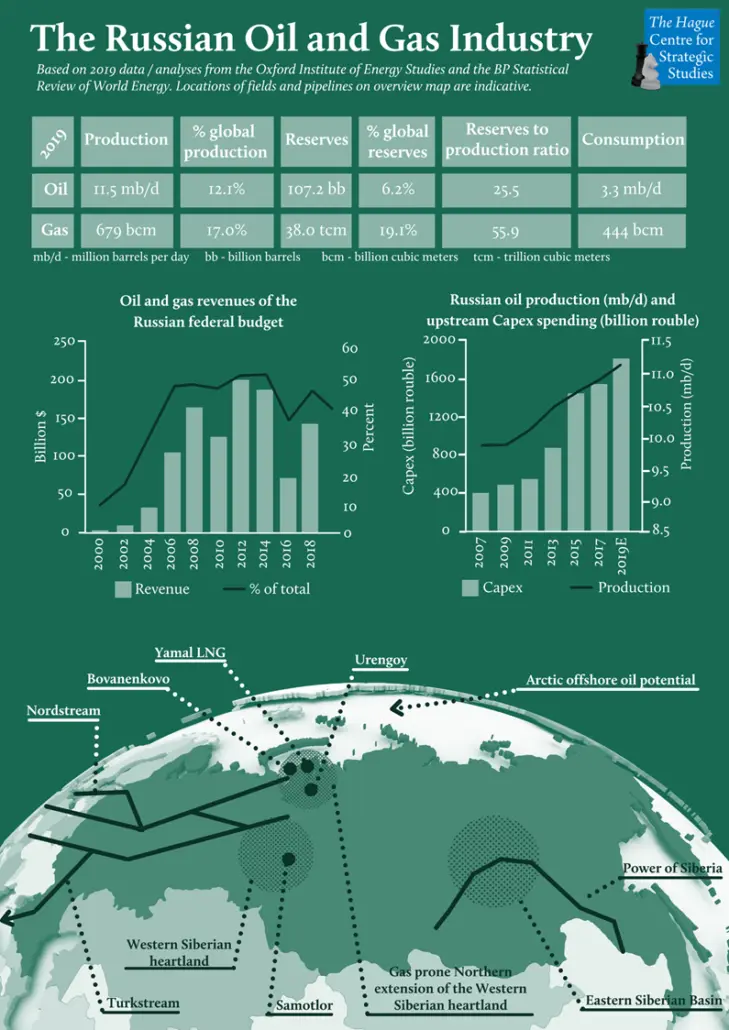

Revenues from oil and gas production are essential for Russia. Over the last decennium, they accounted for 40 to 50% of the Russian federal budget and about two thirds of Russian exports; percentages that are higher than those for the Soviet Union in the 1980’s.

Russia is, with Saudi Arabia and the United States of America (US), one of the top three global oil producers. Russian oil reserves are only the 7th largest in the world, however. The revival of Western Siberia’s giant oil fields, which had seen major reservoir damage under Soviet times, was a significant achievement under the Putin era but has now run its course. Maintaining production levels in these fields, already for decades the backbone of Russian oil production, is becoming more difficult and costly. Exploration for new oil fields in Eastern Siberia has yielded limited success. Unconventional shale oil is a high-cost oil for which the Russian oil industry lacks the technical expertise. Large parts of the Arctic resources lie offshore, and the Russian oil industry has virtually no offshore operating experience. Sanctions are increasingly limiting the Russian oil industry’s ability to maintain production levels.

In contrast to Russia’s more limited oil reserves its natural gas reserves are the largest in the world. The challenge here is not to produce the gas but to transport it and sell it at a profit. The rise of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) shipping now enables the monetisation of remote gas reserves (and these are plentiful) throughout the world. US shale gas is increasingly providing a soft ceiling for gas prices, as US shale oil has done for oil prices since 2014. Russia will remain the key supplier of gas for the European Union (EU) but with the advance of LNG, abundant LNG import capacity within the EU and the liberalization of European gas markets, its influence on gas prices has diminished.

There is a remarkable symbiosis between the Putin regime and the Russian oil and gas industry. Oil and gas are the major source of income for the government. Oil and gas companies will not challenge the primacy of the Kremlin. Gazprom and Rosneft in particular will undertake projects where the geopolitical interests of the Russian government under Putin take preference over commercial considerations. Oil trading, rigged auctions of oil and gas assets as well as the construction of major projects, such as pipelines, at elevated prices, provide ample opportunities for the enrichment of the circle around Putin.

In return, the Russian state provides maximum support for the oil and gas industry. The devaluation of the rouble and numerous tax exemptions have made it possible for the Russian oil and gas industry to further increase investments in the post 2014 low oil price world and to continue to grow production. A highly progressive tax regime shields the oil and gas companies from low prices. US shale production is seen as a threat, but Russia so far chooses to ignore the major transformation of the energy world related to climate change.

Many countries have now started to decarbonise their energy systems, in order to address climate change. Reduced demand for fossil fuels will, in the long run, exert a downward pressure on oil and gas prices. A shift towards low-cost oil is expected. Here, higher cost Russian oil fields will be at a disadvantage against oil from low-cost Middle East producers like Saudi Arabia. Western oil companies are losing interest in high-cost Arctic oil, purely for commercial reasons. Instead, they are starting to transform themselves to energy companies. Russia’s recently published energy strategy to 2035, on the other hand, focuses solely on maintaining oil production levels and increasing gas exports. It chooses to ignore the forthcoming energy transition.

The Putin government is a corrupt regime with limited interaction with the western world (corroborated by the current sanctions). Mining and fossil fuel production are among the few industries that can still function reasonably well in such an environment. A more sustainable business model, competitive in other industry segments, requires a more open and less corrupt society, effectively implying a regime change. Obviously, that is too high a price to pay for the Putin government. It is thus likely to soldier on with its primarily fossil fuel-based business model meaning a slow but steady economic decline.

For how long the economic decline that started in 2014, linked to a heavy reliance upon fossil fuels and the current regimes corruption and geopolitical ambitions, will be tolerated by the Russian population is unclear. What is clear, however, is that the current Russian business model, going all in on fossil fuels, is now facing major challenges and will not be sustainable in the long run.

1. Introduction

In 2019 Russia was the 11th-largest economy in the world. With a nominal GDP of $1.64 trillion it ranked in between Canada and South Korea. In terms of military capacity and fossil fuel production, it is a superpower, however. About 25% of Europe’s oil demand is met by Russia. Close to 40% of gas consumed within the EU in 2019 originated from Russia; a percentage that has risen over the last decade due to declining European, and in particular Dutch, gas production. Given our dependency on Russian oil and gas, a good understanding of Russian oil and gas production is crucial.

Over the last decade, oil and gas accounted for 40 to 50% of the Russian federal budget and about two thirds of Russia’s export (see Factsheet). Whereas in the western world the importance of the oil and gas industry is diminishing, the opposite is happening in Russia. Describing the country that gave us Tolstoy and Solzhenitsyn, and great scientific achievements (such as the International Space Station), as an army with an oil and gas company is not completely without merit. It is the functioning of this oil and gas company, and its prospects in a world that has started to decarbonise, that we want to address in this paper.

Oil and gas play different roles in Russia. Oil and gas production are roughly similar in terms of energy produced (in both cases production exceeding 10 million barrels of oil equivalent per day). Here, however, the similarities stop. Most oil is exported and oil, per unit energy, is worth much more than gas. As a result, about 80% of the proceeds from the export of fossil fuels is derived from oil.

About two thirds of the gas produced is consumed locally for a relatively low, regulated, price. Domestic consumer and industrial prices of 2-3 $/MMBtu now cover costs for domestic producers but are a tiny fraction of what consumers pay in the EU. Natural gas accounts for about 55% of Russia’s primary energy consumption; one of the highest shares worldwide. It is gas that keeps the industry going and that heats buildings. Whereas oil pays the bills, gas props up an inefficient and energy intensive economy and society. Both are essential in today’s Russia.

The EU dependence on Russian gas has been an issue for decades. For a long time, an informal understanding existed within the EU that this dependency should not exceed 30%. However, as EU gas production decreased this percentage has gone up, reaching an all-time high of 39% in 2019. With an increasing share of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) in the global gas trade, abundant gas reserves and ample LNG import capacity within the EU, this has not given rise to major concerns (with the exception of countries such as Poland and the Baltic states); at least not to the extent that effective measures have been taken to reduce this dependency.

Whereas EU dependence on Russian gas has been at the forefront of the discussions, the Russian dependence on the EU as a gas consumer has received far less attention. One can argue, however, that this is the more forceful dependence. With the advance of LNG shipping and trade, the EU now has alternative suppliers. But for Russia, for which most gas exports go to the EU by pipeline, there is no immediate alternative customer for this gas. A gas producer such as Gazprom that relies on pipelines for gas exports has only one customer for its gas: the customer that resides at the endpoint of the pipeline.

Russia’s dependency on fossil fuel production today exceeds that of Brezhnev’s and Gorbachev’s Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. That the prospects for fossil fuel producers have deteriorated so much since 2015 should be a serious concern to the leadership in Moscow.

The Coronavirus pandemic may mark the end of a period in which oil demand was structurally growing and herald a period of “plateau oil”. Efforts to combat global warming by reducing the consumption of fossil fuels are intensifying. Even if we are not anywhere near a trajectory in line with the targets of the Paris agreement this will dampen oil demand. More importantly for oil producers, it will tend to lead to a lower price for oil. It will gradually become more difficult to sustain Russian oil production at its current level, especially if the current sanctions remain in place. Oil production from West Siberia, the heartland of the Russian oil industry, is starting to decline in earnest. Gas reserves are plentiful, but it is a challenge to develop them profitably under the prevailing market conditions. New pipelines are capital-intensive and Russian LNG does not have a cost advantage over other sources of LNG. How does the Russian oil and gas industry – and the government – deal with all these challenges?

2 Russia’s oil industry

2.1 A revival under Putin

With a production of about 11.5 mb/d (million barrels per day) in 2019 Russia was the world’s second largest oil producer. Moscow vies for the top position among oil producing nations with the US and Saudi Arabia. This is no mean feat – given what the oil industry in the Soviet Union and Russia has experienced throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s.

Western Siberia is the heartland of Russia’s oil industry. It was here that a number of world class oil fields were found in the 1960’s and 1970’s. The largest of these, Samotlor, was with 55 billion barrels of oil-in-place the fifth largest oil field in the world.

During Soviet times, production from these giant oil fields was rapidly ramped up. Samotlor on its own was producing about 3 mb/d in 1980; roughly 5% of the global oil production at the time. This was achieved by a massive and aggressive primary waterflood, which involved the large scale injection of untreated water to keep up pressures and maximise initial production. At the time, intense pressure was exerted on Russian geologists to meet ambitious short term production targets, at the expense of long term production potential. Geologists resisting these calls were labelled pessimists and, whilst not ending up in a Siberian labour camp as would have happened under Stalin, they did often end up losing their jobs.

Waterflooding is widely used in the western oil industry, but primarily during the later phases of production in a less aggressive way with more consideration for the ultimate recovery of a field. An aggressive primary waterflood, as done during Soviet times, can greatly harm the total oil recovery from a field.

This is exactly what happened in Samotlor and other Western Siberian oil fields. By the end of the 1990’s Samotlor production had dropped to a mere 0.4 mb/d. The limited remaining oil production was characterised by an extremely high water cut, implying that for every barrel of oil more than 10 barrels of water were being produced. The underground oil reservoir had become a labyrinth of water and bypassed oil. The substantial amount of remaining oil could mostly not be produced with the existing wells. During the 1990’s Russian oil production dropped to a level of about 6 mb/d; roughly half of the peak production during Soviet times of the early 1980’s. The low oil prices at the time and the chaotic privatisation of the oil industry under Yeltsin made it difficult to stem the tide.

The start of the Putin era in December 1999 virtually coincided with the onset of a period of rising oil prices (a period that lasted until 2014). Aided by these higher oil prices the Putin administration has created the conditions where oil producers, provided they accepted the primacy of the Kremlin, could invest and expand production.

Better reservoir management and the massive drilling of infill wells, targeting bypassed oil, in Western Siberian fields have been instrumental in bringing about a resurrection of oil production here. This brute force method has resulted in a large number of wells. In total, Russia now has about 130.000 producing wells. In the West we tend to under-estimate the magnitude of the herculean effort that was needed to bring Russian oil production back to a level in excess of 10 mb/d. The successful management of the oilfields in the Western Siberian heartland is the success story of the Russian oil and gas industry of the last two decades.

Oil production per well is not particularly high in Russia and only a fraction of that in Saudi Arabia. It is the dogged continuation of infill drilling (at a relatively low cost) that has kept production going here. Production levels from the early 1980’s Soviet period (13 mb/d) are no longer within reach. A field like Samotlor will not be able to reach the recovery factor[2] of about 60% for a comparable field like Prudhoe Bay in Alaska and is likely to reach about 40% only (still significantly higher than the 25% it would have reached with Soviet era field development). Water cuts are still relatively high and oil production is relatively energy intensive, relying on cheap electricity from natural gas to run ESP’s (electric submersible pumps), which are widely applied, or to provide power for steam injection.

During the first years of the Putin era there was also a relatively large role for the application of western technology. Independent companies such as Yukos were at the forefront here, applying western style well and reservoir management techniques as much as possible under Russian legislation. Horizontal drilling, in contrast to fracking, is now commonplace in Russia. The shift towards companies closer to the Putin administration such as Rosneft, with a larger amount of state control, slowed down the further application of western technology – already before the time that sanctions became in place.

2.2 Maximum support for the oil industry in the post 2014 low oil price world

Upon the 2014 oil price drop the Russian government has supported the Russian oil industry as much as possible. The devaluation of the rouble has been of great help to oil producers who make most of their costs in roubles and earn most of their proceeds in dollars. A progressive tax system for oil producers reduces the downside of a low oil price (but also the upside of a high oil price).

On average, Russian oil producers now require an oil price of about $35 per barrel to be profitable (post tax). Losses at lower oil process are relatively small. For oil production from difficult areas and plays a (partial) exemption of taxes is frequently granted. Lower oil prices and an increasing part of production from more difficult plays (or very mature fields with a higher production cost) have resulted in a growing number of (partial) exemptions. It is estimated that the fraction of Russian oil production that has a partial tax exemption has now grown to about 60%.

The consequences of a period of low oil prices are to a large extent borne by the Russian state and not by Russia’s domestic oil companies. Russia’s relatively low debt and substantial financial reserves enable it to play this role for a significant amount of time. Russia’s federal budget currently balances at an oil price of little over $40 per barrel.

As a consequence of these policies, Russian oil producers have been able to keep up investments, in marked contrast to western oil companies. As a result, Russian oil production has continued to increase from 2014 to 2019. Upstream investments are now a factor 3 higher than a decade ago, (see also the factsheet) whereas global upstream investments have decreased over this period. The cost of these policies is borne by the Russian state and the Russian people for whom the devaluation of the rouble has resulted in a marked decrease of living standards as many consumer goods are imported and have become more expensive.

With a current production capacity of over 11 mb/d, Russia’s production capacity is now comparable to that of Saudi Arabia and the US. Compared to the late 1990’s, production has almost doubled. This is a significant achievement. It is also the maximum that can be reached with the existing focus on the Western Siberian oil fields.

2.3 Russian oil: sharing the spoils among “friends”

Russian oil and gas companies are often run by people that have a close and long standing connection with Vladimir Putin. Rosneft is run by Igor Sechin, an ex-KGB officer and Putin’s former right-hand man during his time as deputy mayor in St Petersburg in the 1990’s. Gazprom’s CEO Alexey Miller is also a Putin connection from his St Petersburg days. It is their loyalty that is of vital importance, more so than their technical and commercial achievements. They are generously rewarded for their efforts and sufficiently secure of their position to flaunt their wealth. By way of illustration: Sechin’s yacht is worth an estimated $ 190 million.

The relatively large degree of freedom that oil and gas companies enjoyed under Yeltsin was rapidly lost during the first years of the Putin era. Mikhail Khodorkovsky challenging the primacy of the government resulted in the split up of Yukos (with the key assets ending up with Rosneft) and a 10-year spell in jail (followed by exile). Oligarchs from the Yeltsin era have gradually lost influence, and in some cases their assets as well.

The primacy of the Kremlin does not mean that there is a strict, detailed, all-encompassing plan for the Russian oil and gas industry. Neither is there a single, dominant national oil and gas company. Gazprom may be the dominant gas producer, but it is Novatek that is taking (or has been given) the lead in LNG. Rosneft is the country’s biggest oil producer but still only accounts for about 40% of the total Russian production. Rosneft and Gazprom chiefly serve the Kremlin’s ambitions and geopolitical interests – to a greater extent than other companies. These two large state-controlled producers tend to be less efficient than independent producers. Their investments in research and development are minimal at 0.02 and 0.09% of turnover respectively; a fraction of what western oil and gas companies spend. In contrast to their domestic competitors, Rosneft and Gazprom are willing to take on large debts. Together, these two companies are responsible for 90% of the total net debt of the Russian oil and gas sector of $118 billion. Serving the Kremlin takes preference over the interests of their shareholders.

Companies like Surgutneftegaz and Lukoil tend to have a better technical track record than Gazprom and Rosneft. What is lacking in Russia, however, are small niche companies. That licenses cannot be transferred, but have to be given back to the state, effectively precludes the emergence of small niche operators.

Influence can be transformed into money, and vice versa, but in the end, it is influence that matters the most. Good contacts and protection are more important than good contracts. Vladimir Yevtushenkov’s Sistema holding was forced to give up its majority share of Bashneft to the state; a share that subsequently ended up with Rosneft.

All Russian oil and gas companies aim to have a good standing with Vladimir Putin whose role has, not without reason, occasionally been compared to that of a leader of a criminal organisation. For outsiders, this is a murky and opaque world. Tax exemptions are frequently granted and the ability to secure such exemptions has a large influence on profitability. Apart from taxes, a substantial part of the revenues is distributed by different means. Frequent payments (either in the form of money or services) are made to local authorities. Services such as drilling or the construction of plants or pipelines are granted to service companies at inflated costs. The resulting profits are shared amongst numerous stakeholders. “You make money from your profits but we make money from our costs”, a Russian manager is quoted in Thane Gustafson’s Wheel of Fortune, a seminal work on the Russian oil industry.

The Russian oil and gas industry is the primary sector through which Putin’s entourage is able to enrich itself. Whilst Rosneft and Gazprom heads Sechin and Miller receive much publicity, other members of Putin’s inner circle with powerful positions in the oil and gas industry tend to stay more out of the limelight. Gennady Timchenko made his money in oil trading with Gunvor and is also a shareholder of Novatek. Gunvor was, between 2005 and 2010, making large profits by buying oil from Russian oil companies at a discount (primarily from Rosneft who at the time did not solicit bids from other traders when selling its oil) and by manipulating the price of Urals (the most important export grade, and benchmark, for Russian oil). Arkady Rotenberg owns the major contractor for pipeline construction. Yuri Kovalchuk is the CEO of Bank Rossiya, the bank that plays a key role in managing the fortunes of many members of Putin’s entourage.

The Putin government and the Russian oil and gas industry have a symbiotic relationship. The Russian state under Putin has provided maximum support for the oil and gas industry. Oil and gas, on the other hand, have been the major source of income for the government and Putin’s entourage. Oil trading, rigged auctions of oil and gas assets as well as the construction of major projects, such as pipelines, at inflated prices, provide ample opportunities for the enrichment of the clique around Putin, still primarily consisting of former members of the security services and acquaintances from Putin’s spell as deputy major in St Petersburg.

2.4 Russia: not a swing producer

Russia’s policy on oil production and prices is to produce close to its production capacity. They are willing to cut production in a crisis, like the current corona crisis, but remain sceptic about substantial production cuts under normal conditions. They were willing to go along with Saudi Arabia (2016-2020) but only with production cuts substantially smaller than those of the Saudis, who had to shoulder most of the burden.

In Russia’s view the loss of market share, primarily to US shale oil, is too much of a price to pay for temporary higher oil prices. They feel it makes no sense to push for a price higher than an equilibrium price at which US shale oil production (and in the much longer run: conventional non-OPEC+ production) remains relatively constant. The 2016-2020 cooperation between Russia and Saudi Arabia was a marriage (or perhaps: affair) of convenience made possible by Saudi Arabia’s willingness to take on a relatively large share of the production cuts.

Russia’s policy on oil production is similar to the old, pre-2016, Saudi Arabia policy under oil minister Ali al Naimi: to maximise revenues from oil in the long term. The fact that Russia’s federal budget balances at a little over $40 per barrel, its ample financial reserves and a low debt of the Russian state enable the government to do so. Saudi Arabia, by contrast, currently needs an oil price about twice as high for its federal budget to balance and thus has less leeway to give preference to long term objectives over short term considerations. When the dust settles after the corona crisis, it is expected that Russia will be more reluctant than Saudi Arabia to implement production cuts to prop up oil prices in the short term.

On top of the financial considerations, it is also more difficult from a technical point of view for Russia to accommodate large variations in oil production. Low oil production wells with a high water cut can see permanent reservoir damage if they are shut off for a prolonged period of time. Maintaining the flow of oil in pipelines under very low temperatures is not straightforward. Associated gas from oil wells in Russia often plays an important role in local power generation or heating. The Russian oil production system is much more complex than that of Saudi Arabia and has more difficulty to accommodate sudden large swings in production levels.

2.5 Geology: an increasing challenge to maintain production

Managing the decline of conventional brownfields in the western Siberian basin, the mainstay of Russian oil production in the two decades under Putin, is becoming more difficult. Average production costs have gradually risen to about $20 per barrel and are expected to rise to about $30 per barrel in 2030. Water cuts are increasing and as a result oil production is requiring more electricity (mostly gas generated). The amount of oil that can be produced from an additional infill well is decreasing. Between 2008 and 2019, the average additional production from a new Russian well dropped by about 13%. For the western Siberian brownfields this drop was substantially larger, at 49%. Russian oil production will plateau, and subsequently decrease, if new plays in regions outside the western Siberian heartland do not take off in earnest. Moscow is well aware of the situation and has tried to address it but so far only limited progress has been made in establishing oil production from new regions or plays. A number of options exist.

Firstly, there are the Central and Eastern parts of Siberia. During the last decade exploration here for new oil and gas fields has stepped up, in particular by companies like Surgutneftegaz and Rosneft. These exploration campaigns have only seen limited success, however. New discoveries were made but the size of these discoveries was nowhere near the size of the western Siberian fields. About 10% of total Russian oil production now comes from Central and Eastern Siberia; a percentage that is unlikely to increase much further.

Secondly, there is the potential for shale oil production from the Bazhenov shale in western Siberia (the source rock for the western Siberian oil fields). Among the western oil majors the Bazhenov shale in Russia and the Vaca Muerta shale in Argentina are generally considered, from a geological point of view, to be the most attractive shale oil areas outside the US. Joint ventures between Russian and western companies, aiming to test the Bazhenov, have all been closed down upon the imposition of financial and technological sanctions following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. The Russian oil industry on its own is not capable to get Russian shale oil production off the ground. It is doubtful if Bazhenov production (or any shale oil production outside the US) can be commercially attractive at all, even with access to western technology, in the current low oil price environment.

Finally, there is the potential for oil in the Arctic areas, either offshore or in northernmost Siberia. The main problem here is that the onshore extension of the western Siberian oil and gas fields towards the North is primarily yielding new gas fields (in the north of Siberia and near the Yamal peninsula). This has become the main growth area for the Russian gas industry. The potential for oil is greater in Arctic offshore areas further North where ExxonMobil and Rosneft made a discovery in 2014. Offshore implies higher costs, however; in particular in a harsh environment such as the Arctic. Over the last few years western oil companies have largely given up on the Arctic – not just for environmental, but also for commercial reasons. For the Russian oil industry, which is almost exclusively operating onshore, this is a major challenge. Rosneft has recently indicated to be willing to invest $135 billions for the development of oil fields on the northern Siberian coast under the condition that it is granted a tax exemption worth over $40 billion. This project (Vostok) is still in an early phase.

The limited scope for new oil from areas outside the western Siberia heartland implies an increasing challenge to maintain oil production at the current level. The focus on getting the most out of the existing brownfields is likely to continue. This is where the core strength of the Russian oil and service industry lies. In the west we tend to underestimate how big the challenge is to limit the decline for western Siberian brownfields and open up new plays, far outside Russia’s oil industry comfort zone and under harsh conditions.

The targets formulated in Russia’s Energy Strategy to 2035 do not include a further growth of Russia’s oil production. The 2025 target is equal to the production level attained in 2018 and for 2035 there is a small decrease foreseen. A recent evaluation of this strategy by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) indicates that these targets are challenging – in particular if sanctions remain in place. For a low case scenario (low oil prices and a continuation of sanctions), a substantial drop of Russia’s oil production in 2035, up to about 30%, could materialise. Although the effect of sanctions may be relatively small in the short term, it is substantial in the long term. Russia’s energy strategy focuses on even greater efforts to maintain oil production. No vision on a future beyond oil and gas has yet been developed.

The Russian oil industry may well face a perfect storm during the coming decade. An increasing challenge to maintain production levels and rising costs for new oil will coincide with a period in which the decarbonisation of energy systems in many countries outside Russia takes off in earnest. This will exert a downward pressure on oil demand and oil prices. So far the Russian government has effectively chosen to ignore these developments. Many researchers (e.g., energy analysts from the Skolkovo Institute) and more liberal minded politicians, such as Medvedev, are well aware of these developments but their influence in the Putin administration is limited.

3 Russia’s gas industry: how to monetise those huge reserves?

3.1 Gazprom: a giant facing increasing competition

Russia has, with about 20% of the global, proved reserves, the largest gas reserves in the world. The challenge is not to find and produce gas but to transport and sell it. How to monetise all those Russian gas reserves in a world where gas is relatively abundant and where LNG now allows competitors like the western majors to monetise remote gas assets that used to be considered stranded?

Gas is different from oil. Oil can be shipped by tanker and moved across the world at minimal cost. The transport of gas, on the other hand, is expensive. Traditionally, gas has been transported through pipelines with a large upfront cost and relatively low running costs. Over the last 20 years, transport of LNG has taken off and currently about 45% of global international natural gas trade is LNG based. LNG has both significant upfront and operating costs. However, it has the advantage of flexibility and enables the transport of gas over long distances, in excess of several thousands of kilometres, where the costs of constructing pipelines becomes prohibitive.

With a share of about 55% in primary energy consumption natural gas plays a central role in Russia’s energy system. This also means that Gazprom plays a central role. Unlike oil producers, which were sold off at rock bottom prices throughout the 1990’s in order to support the state finances (and finance Yeltsin’s 1996 re-election), Gazprom survived the chaotic 1990’s pretty much intact: partly because of the pivotal role of gas for Russia and partly because of the powerful position of Victor Chernomyrdin. Throughout the 1990’s Gazprom kept on supplying Russia with the bulk of its natural gas production, at minimal prices (with payment often not taking place at all), making its money from gas exports to the EU (the “fifth molecule”). It was only after Chernomyrdin’s successor, Rem Viakhirev, was replaced by Putin’s crony Alexey Miller (bringing Gazprom again under full Kremlin control) that the plundering of Gazprom began. Gazprom lost its drilling and pipe laying service companies but kept most of its producing assets, pipeline network and monopoly on gas exports.

For a long time, the West Siberian heartland was also the backbone of Russia’s gas production. But around the year 2000, the older giant gas fields here, Medvezhye and Urengoy in particular, started to decline more rapidly. The Western Siberian basin becomes more gas prone towards the North and plenty of undeveloped gas reserves were waiting to be developed here. Over the last 2 decades, Gazprom has increasingly shifted focus for new gas to the greater Yamal area. Bovanenkovo, the largest field in this area, started to produce in 2012 and is now producing in excess of 100 bcm/yr (billion cubic metres per year). Production links to the existing Yamal and Nordstream pipeline systems.

Gas giant Gazprom now faces increasing competition. Other gas producers are increasing their share on the domestic market, primarily targeting industrial users (preferably at a limited distance from their gas producing assets) with gas prices below the regulated gas price that Gazprom has to stick to. Gazprom has remained a relatively conservative pipeline company with little experience in LNG (the only LNG project that Gazprom is operating in Sakhalin was built by Shell). Its new pipelines (Nordstream 2, Turkstream and Power of Siberia) require large investments. Although it has retained its monopoly on pipeline exports, competitors Rosneft and Novatek are now permitted to export LNG. Gazprom’s share of Russian gas production had fallen to 68% in 2017.

3.2 LNG changes the world of gas

Oil tankers have been sailing across the oceans for decades, yet for LNG carriers this is a more recent development. The global number of LNG carriers has risen to about 600, and is rising fast. LNG now enables the US to continue increasing gas production, exporting what is not consumed locally, and enables Asia (where long distance pipeline networks are scarce), in particular China, to continue increasing gas consumption.

The rising trade in LNG has resulted in a convergence of natural gas prices on the major gas markets (US, Europe and Asia). Market leader (and lowest cost producer) Qatargas can ship LNG to Europe or Asia and the cost at destination will be similar. The scope for a period of very high gas prices on one of these markets, as occurred in Asia in 2011-2014, post Fukushima, has become smaller. Competition has increased and plentiful low-cost US shale gas can be delivered worldwide at a cost price of about $6/MMBtu, exerting a downward pressure on gas prices.

Over the last 15 years, the share of shale gas in the US production has risen from 5 to 70%. During this period yearly production doubled to about 1000 billion cubic metres (bcm) (Russia’s current production is about 700 bcm). From 2017 onwards, the US has become a net natural gas exporter. Worldwide, remote and previously stranded gas fields can now be monetised (provided volumes are sufficiently high and the cost of production and building a liquefaction plant are sufficiently low).

For a country such as Russia that relies mostly on pipeline exports, the rise of LNG and US shale gas has been worrying. Since 2012, following the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, Putin has pushed Gazprom to become more active in LNG. Gazprom has been slow to pick up on this. Its pipeline projects require major investments and internally there has been a long term battle between LNG proponents and opponents. A number of LNG projects, Shtokman, Baltic LNG and Vladivostok LNG, have been proposed and subsequently postponed or cancelled by Gazprom. Potential western partners may be interested but are reluctant to let Gazprom-friendly Russian partners build LNG plants at inflated costs. Shell recently pulled back from the Baltic LNG project when Gazprom announced that the LNG plant and an associated petrochemical complex would be built by RusGasDobycha.

Gazprom losing its monopoly on LNG exports (whilst retaining it for pipeline exports) opened up the door for its competitors. It is Novatek, rather than Rosneft, that has taken the lead here. Under the leadership of Leonard Mikhelson, Novatek had become Russia’s largest independent gas producer and was known as a low-cost producer with a good technical track record. In addition, it had a highly profitable focus on the production of condensates – a liquid by-product from gas fields that received little attention from Gazprom. Novatek’s other major shareholder, Gennady Timchenko, provides political protection and is likely to have been instrumental in securing tax exemptions.

Novatek’s project management is superior to that of Gazprom and, to the surprise of many industry experts, it has delivered its Yamal LNG plant on time and on budget in 2017. Partners Total and CNPC have assisted on the technical side (Total, using technology from France’s Technip and Germany’s Linde) and on the financial side (CNPC; close to 60% of the financing for Yamal LNG came from China). Novatek has been allowed to order LNG carriers from low-cost suppliers in South Korea rather than from Russian suppliers with higher costs.

Gas is produced from conventional gas fields situated close to the coast. With the Arctic LNG-2 project yearly capacity is planned to increase from current 25 bcm to over 50 bcm in 2025. Ambitious plans exist to further expand LNG capacity to close to 100 bcm in 2030 implying that Russia will join a select group of major LNG suppliers (currently: Qatar, US and Australia). Novatek’s LNG projects are a financially more attractive way of finding new customers for Russian gas than Gazprom’s loss making Power of Siberia pipeline. Novatek is shaking up the Russian gas industry, not unlike Yukos once did for the oil industry, but it is doing so as a system insider rather than as a system outsider.

3.3 Russian gas and the EU: condemned to each other

Over the last 50 years we have witnessed the cold war, the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Putin era, the annexation of Crimea and the subsequent imposition of sanctions. All those years, the export of gas from the Soviet Union / Russia to the EU has continued. In the background, behind all the political developments, there is something that does not change: Russia has the largest gas reserves in the world, Europe has a large demand for gas and in between Russia and the EU there is an existing pipeline network. With the costs of the bulk of this network long amortized, Gazprom can deliver gas to the EU at very low cost; way below the cost of LNG. With respect to natural gas Russia and the EU are condemned to each other.

The cost price at the western Russian border is estimated to be slightly less than $2/MMBtu (mostly transportation costs rather than production costs). The cost of LNG amounts to about $4/MMBtu (operational cost, excluding the cost of an LNG plant) – $6/MMBtu (full cycle cost, including the cost of an LNG plant). The latter cost is similar to that of Russian piped gas if the cost of a new pipeline needs to be included.

Germany has always played a central role in the energy relationship between Europe and Russia. It is the largest customer for Russian gas and German companies played a key role in the construction of the Russian export pipeline system. It was part of Germany’s Ostpolitik and the later good relationship between former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Vladimir Putin under the motto Annäherung durch Verflechtung (rapprochement through linkage). Annäherung with Putin has turned out to be an illusion (in Angela Merkel’s words: “Putin lives in his own world”) but the Verflechtung is, at least when it comes to natural gas, de facto there. Gazprom’s piped gas exports to Europe reached a record level of close to 200 bcm in 2018 and 2019.

The total EU-28 yearly capacity to import LNG is approximately 220 bcm. Between 2010 and 2015 this capacity was only used for about 20%. Over the last few years, this percentage has grown to close to 50%, especially after the 2018 emergence of an oversupply in LNG (due to a number of new LNG plants) and the associated fall in gas prices. Rising EU ETS (EU Emissions Trading System) prices for carbon emissions (promoting coal to gas switching) and falling domestic production also played a role. With the stream of new LNG plants continuing until 2020 and the current corona crisis reducing demand, LNG oversupply is unlikely to disappear in the near future.

Europe has a large absorption capacity for LNG due to its large import capacity and the option to replace coal-fired power by gas-fired power. It has effectively become the global swing consumer for gas; the market of last resort. This implies a greater probability for a buyer’s market for gas, where Russian piped gas and LNG have to compete. LNG limits the capacity of Gazprom to raise prices. The EU has an alternative source of gas, or at least a sizeable portion of it, but Gazprom does not have an alternative destination for its piped gas. The dependency of Russia on the EU as a gas consumer is greater than the dependency of the EU on Russia as a gas producer.

Apart from LNG, other developments have also decreased Gazprom’s power. The EU’s 2009 Third Energy Package opened up gas markets in Europe. Vertically integrated companies had to be broken up, separating production companies from their transmission networks. In a new pricing environment, the link with oil prices was abandoned and was replaced by a more competitive setting where gas prices were set at hubs in a market environment. Gazprom has since had to accept the demise of its traditional oil-indexed contracts.

At this point in time, Gazprom’s yearly piped export capacity to Europe amounts to about 230 bcm. Nordstream 2, if finished, will add a further 55 bcm. With 2019 record exports of some 200 bcm (substantially lower in 2020 due to the corona crisis), and a new Ukraine transit agreement in place, there is no urgent operational need to finish Nordstream 2.

One can look at Nordstream 2 as a commercial project that counts on a long term increase of Russian gas exports, in excess of the current capacity of the pipeline network. Although not impossible, this requires falling production, a relatively stable EU gas demand ánd a limited increase of LNG imports. To regard it as a geopolitical project that allows Russian gas exports to the EU to bypass Ukraine is, in our view, more convincing. It should also be noted that whereas pipelines such as Nordstream2 (which also involves extensive onshore pipeline construction) and the Power of Siberia seem only marginally commercially attractive to Gazprom they are highly profitable to Gazprom’s contractors such as Stroygazmontazh, Russia’s largest pipeline construction company (owned by Arkady Rotenberg, one of Putin’s closest associates, and the father of Igor Rotenberg, Gazprom Drilling’s largest shareholder).

At the time that US sanctions forced Dutch/Swiss Allseas to withdraw its pipe laying vessels, over 90% of the Nordstream 2 pipeline was completed; with only part of the section in Danish waters missing. The Russians may still be able to complete the pipeline; either by upgrading the Akademik Cherskiy pipe laying vessel (in its current configuration the maximum pipe diameter that this vessel can handle is less than the diameter of the Nordstream 2 pipe) or by hitching together the Akademik Cherskiy and the Fortuna (using ships with anchors instead of DPS is now permitted following clarification from the Danish EPA government agency). Whether they will actually be able to do so, once that US sanctions also apply to insurance companies and verification companies, remains to be seen.

Methane emissions associated with the production and transport of Russian gas are substantial and will become a bigger issue. It will not be straightforward to resolve this for Russia’s relatively old production systems and pipeline networks.

3.4 Deteriorating prospects for Russia to make money from gas

Russia’s gas reserves are plentiful and they allow for a larger production as envisaged in Russia’s latest energy strategy (about 30% higher in 2035). The challenge is not to produce the gas but to transport and sell it – and most of all: to make money from it. A number of developments imply decreasing prospects to make money from Russian gas.

The rising trade in LNG implies that remote gas reserves can now be developed by the western majors. For these companies gas reserves are easier to find and more accessible than oil reserves. They have jumped upon this opportunity, seeing natural gas as a bridge fuel in the energy transition. Competition between LNG suppliers is expected to intensify. LNG may become a success story – from a volumes point of view, rather than a financial point of view. Cost wise, within this competition, Russian LNG is at a disadvantage relative to market leader Qatargas and is expected to have similar costs as US shale sourced LNG.

Global demand for natural gas may still rise with the hot spot for gas demand growth located in Asia. Coal to gas switching in countries such as China results in a rapid reduction of both pollution in urban centres as well as CO2 emissions. The lack of pipeline infrastructure in many Asian countries and the isolation of many of its key markets mean that LNG will be the main source of gas supply, rather than piped gas.

Russia will remain the main supplier of gas for the EU, yet with abundant LNG import capacity within the EU and the liberalisation of EU gas markets following the implementation of the EU’s Third Energy Package, Russia’s influence on prices has diminished.

The combination of inexpensive US and Middle East gas, a rising share of LNG in the international gas trade and a smaller than expected demand growth in a world that is becoming more serious about tackling climate change will exert a systematic downward pressure on gas prices. This is a problem for Russia, just as well as it is for the western majors. They are both gradually shifting towards natural gas but for both of them gas is unlikely to take over the role of the big money-maker from oil. In this changed environment for the Russian gas industry an expensive new pipeline project like the Power of Siberia pipeline seems a hazardous undertaking. Using the existing pipeline network as a cash cow (augmented by some LNG projects) seems a much more commercially attractive strategy than building new pipelines. As for oil, the Russian gas industry is slow to adapt to an industry environment that has fundamentally changed.

4. Concluding remarks

From a political point of view Putin’s position may look strong. Within Russia no major challenges to his administration have appeared yet. There have been demonstrations in Moscow in 2012 and recently in the provinces, like in Khabarovsk, but overall, the atmosphere under the Russian population is one of disinterest in political matters and resignation (something that may rapidly change as we have recently seen in Belarus).

From an economic point of view Putin’s position does not look strong at all. Over the last decade Russia’s share of the global GDP has almost halved. Its economy remains heavily dependent on oil and gas revenues. This dependence is increasing rather than decreasing and is now greater than that for the Soviet Union in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Whilst the western world is moving away from fossil fuels, Russia is doubling down on oil and gas. Over the last decade upstream investments in Russia have tripled and as a result the decline of Western Siberian giant oil fields was temporarily halted. This business model, going all in on oil and gas, is not sustainable.

Arresting the decline of oil production levels in Western Siberian oil fields, already for decades the backbone of Russian oil production, is becoming more difficult and costly. The strategy that has been applied to maintain production here, increase investments and grant ever more tax exemptions, has now run its course. If Russia’s oil production is to stabilise over the coming decade, more oil needs to come from other areas, and this is a major challenge.

The results from exploration campaigns for new conventional oil in Central and Eastern Siberia have been disappointing and the potential for these areas is limited. Russia’s oil industry lacks the technical expertise to develop shale oil in the Bazhenov. Even if sanctions are lifted it is unlikely that this high-cost oil is attractive to develop from a commercial point of view. Russia’s Arctic oil resources are mostly offshore and the Russian oil industry lacks sufficient offshore operating experience. Over the last decade, western companies have lost interest in such high-cost oil in environmentally sensitive areas. Rosneft’s proposed Vostok project near the Northern Siberian coast has made little progress so far and needs major tax exemptions.

In contrast to oil, Russia’s natural gas reserves are not a limiting factor. Monetising gas has become more difficult, however. The rise of LNG trade and US shale gas have made competition on gas markets more intense. Russian gas, when transported through the existing pipeline network to the EU, has a cost advantage over other sources of EU gas imports. But for Russian LNG, or for expensive new pipelines such as Nordstream 2, this is not the case. Likewise, the business case for Russia’s Power of Siberia pipeline to China looks bleak. Whereas Russian gas production volumes may further increase over the coming decade, its profitability may decrease in a world where LNG, US shale gas and lower than expected natural gas demand (in a world where climate change is finally taken seriously) all exert a downward pressure on gas prices.

Russia’s recently published energy strategy to 2035 is all about maintaining or increasing oil and gas production and ignores the changing prospects for fossil fuels due to the energy transition. Barring a regime change, the symbiosis between the Putin administration and the Russian oil and gas industry is likely to persist. Oil and gas are the major source of income for the state. Oil trading, rigged auctions of oil and gas assets and the construction of oil and gas projects at inflated prices are the major sources of income for the Putin clique. In return, the Russian state has supported the oil and gas industry in the wake of the 2014 oil price collapse by devaluating the rouble and by granting numerous tax exemptions. A highly progressive tax regime shields the oil and gas companies from low oil prices.

Mining and fossil fuel production are among the few industries that can still function reasonably well under the corrupt Putin regime. To be competitive with the outside world in other industries requires a more open and less corrupt society. Such a change cannot be brought about under the Putin regime which is doggedly soldiering on with its outdated fossil fuel-based business model. For how long it will be able to do so is unclear. The longer it takes, the more likely it becomes that Putin will oversee the continued stagnation of the Russian economy and that his place in history will be that of a Brezhnev2.0.