-

Conflict in Cyberspace

-

Introduction

-

Threats in Cyberspace

-

Intentions

-

Capacity

-

Activities

-

International Order in Cyberspace

-

Conclusion: Building Bridges Between Multilateralism and Multistakeholderism

-

Appendix A: States’ First Disclosure of Offensive Cyber Capabilities (non-exhaustive)

-

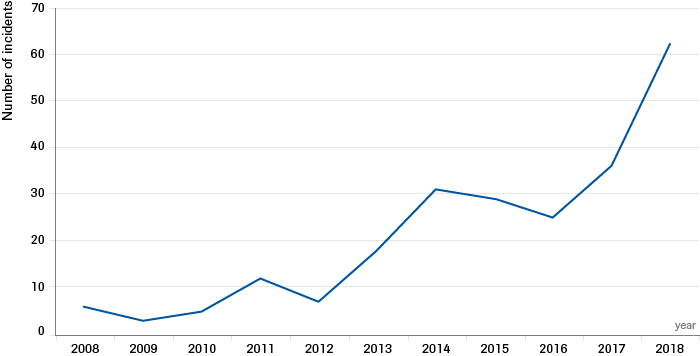

Appendix B: Timeline of Major Cyber Incidents 2009-2019

-

The Global Security Pulse (GSP) on Conflict in Cyberspace was published in June 2019 and tracked emerging trends in relation to peace and security in cyberspace.[1] This complementary research report delves into the two trend tables presented in the GSP by examining their underlying quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Disclaimer: The research for and production of this report has been conducted within the PROGRESS research framework agreement. Responsibility for the contents and for the opinions expressed, rests solely with the authors and does not constitute, nor should it be construed as, an endorsement by the Netherlands Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense.

Introduction

This paper examines conflict in cyberspace through a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the intentions, capabilities, and activities[2] of state actors in this domain, as well as an analysis of the norms and rules relevant to cyberspace. Its principal conclusion is that conflict in cyberspace has exponentially intensified in recent years, earning a top spot among states’ most critical security concerns. This is not without reason. Cyber operations are taking a leading role in conflicts between states and recently the risk of a major cyber incident between nation states has been described as a major threat in national security strategies. Earlier this year, Russian groups purportedly took aim at liberal democratic processes once again by targeting European voters with disinformation ahead of the EU elections.[3] Meanwhile, the recent Netnod attack on the Domain Name System (DNS), which was reportedly conducted by Iran, highlighted vulnerabilities within critical internet infrastructure and served as a reminder to the Dutch of the 2011 DigiNotar breach.[4] As Sino-American relations deteriorate, there has also been an increase in reported Chinese cyber espionage.[5] Undoubtedly, malicious actors are using cyber means, including cyber espionage, Computer Network Attacks (such as attacks on the DNS) and disinformation campaigns, to wreak havoc on international peace and security. While this dire outlook is partially connected to the overall level of geopolitical tension, there is a significant concern that the ability of governments to successfully manage the threat of major conflict is impeded as they only make up one of three actor groups in the overall cyberspace regime complex.[6]

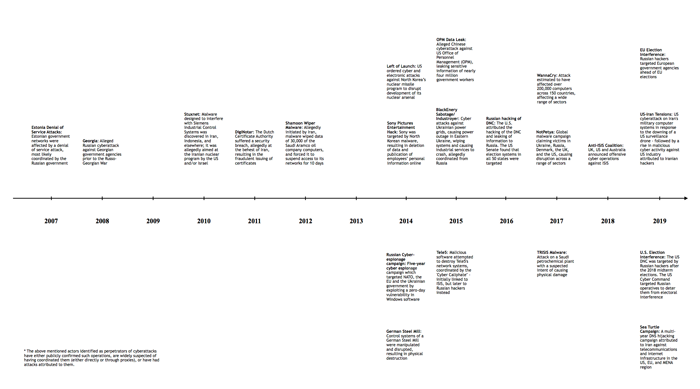

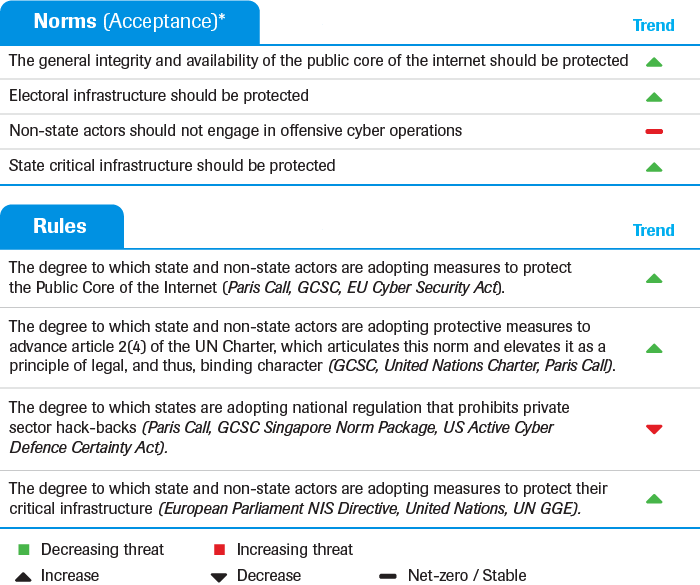

The Global Security Pulse (GSP) on Conflict in Cyberspace was published in June 2019 and tracked emerging trends on peace and security in cyberspace.[7] This research report delves into the two trend tables presented in the GSP by examining their underlying quantitative and qualitative evidence. First, the ‘Threats in Cyberspace’ trend table, which measures a variety of indicators over a period of ten years (Table 1), is examined. These indicators measure the seriousness of conflict in cyberspace by gauging the intention and capacity of states to engage in cyber conflict, as well as the level of malicious activity reported in cyberspace. The report continues with an analysis of the second trend table (Table 4), ‘International Order in Cyberspace’, which measures the acceptance of norms and rules in this contentious field. Lastly, the conclusion illuminates how states can forge norm coherence and adoption in this complex, multi-stakeholder environment in order to enhance stability and peace in cyberspace.

Threats in Cyberspace

Intentions

Perceptions of interstate escalation of tensions in cyberspace

An increasing number of national security threat assessments have identified cybersecurity as the main or a major security threat.[8] Throughout all eight analyzed National Security Strategies (US, DE, FR, UK, CN, RF, IN, NL) there is a rising perception that tensions between states is escalating in cyberspace. The earlier strategies (2006 - 2013) place a similar focus on the domains in which cybersecurity is regarded to be of relevance, i.e., cybercrime, IT theft, espionage, sabotage, inter-state cyber military competition, or the protection of critical infrastructure. Six out of the eight most recent strategies (2015 - 2019) place a higher priority on the relevance of cyberspace for national security, in particular the threat from state actors. Previously, although malicious governments seeking to advance their respective national interests were mentioned as a potential threat, more focus was placed on cybercriminals. In contrast, more recently, dedicated national cybersecurity assessments also identify a rising threat of state actors in cyberspace due to the increasing deployment of state-affiliated or directed cyber operations for offensive purposes. A notable point of contrast between the earlier and more recent national security strategies in regard to cyberspace is the recognition of cybersecurity as one of the main threats to national security.

Both bilateral and multilateral interstate discussions have attempted (and in some cases managed) to address some of the risks involved in inadvertent escalation as well as a loss of escalation control.[9] Most notably, the application of international law, norms of responsible state behavior, and confidence building measures (CBMs) have functioned as stability mechanisms that establish ‘rules of the road’ for responsible state behavior in cyberspace. More recently, states are shifting their attention to a more forward-leaning deterrence mechanism, the threat of punishment, to complement the deterrence measures of denial by defense, entanglement, and normative restraints.

Deterrence largely hinges on perception, as noted by Joseph Nye: “its effectiveness depends on answers not just to the question of 'how' but also to the questions of 'who' and 'what'. The threat of punishment – instead of deterrence by denial, entanglement, or norms – may deter some actors but not others.”[10] As state-led offensive cyber operations proliferate in a legal gray area without enforcement mechanisms to punish bad behavior, there is a significant concern that defensive deterrence measures (especially denial through cyber hygiene, defense and resilience) fall short against major states. An intelligence or military agency of a tier 1 cyber power is likely to penetrate most defenses with the right resources, but the combination of threat of punishment and effective defense can influence their calculations of costs and benefits. This is illustrated by the new US doctrine of “persistent engagement” that is designed to not only thwart adversary cyber operations by continuously anticipating and exploiting their vulnerabilities, but also to reinforce deterrence by raising the costs for adversaries (for example by denying their ability to exploit US vulnerabilities through operations that support resiliency, defending forward, contesting and countering to achieve strategic advantage).[11] However, this doctrine runs the risk of undermining allies’ trust and confidence and may cause diplomatic friction when the US decides to operate through the networks of its allies – something that could be easily exploited by common adversaries. Furthermore, it could pose a danger of escalation if interstate relations, especially the lines of communication, are poor.[12] Ultimately, each deterrent mechanism should not be seen as individual stand-alone components, but as complementary approaches to affect actors’ perceptions of the costs and benefits of actions.

States disclosing offensive cyber capabilities to enhance transparency

The lack of transparency in presumed force deployment, and even the method of operation or intended effects, make the task of assessing a state’s intentions, capabilities, and activities difficult. States are left guessing the overall capability of another state (albeit at widely varying degrees of detail) without, for the most part, being able to detail the exact order of battle, table of equipment, tactics, techniques, procedures or other basic information – unless the intelligence assessment is very complete.[13]

In their joint statement before the US Senate Armed Services Committee in 2017, the US Director of National Security and Director of the NSA and the US Cyber Command issued a warning that thirty countries are developing offensive cyberattack capabilities.[14] More recently, an increasing amount of states have disclosed that they have offensive cyber capabilities. Appendix A of this research paper includes a sample of official statements that represent states’ first disclosure offensive cyber capabilities. While this trend may be interpreted by some as an escalatory step towards the militarization of cyberspace, a more nuanced interpretation could describe it as a transparency measure. The motivation behind this decision can therefore be seen as a necessary first step towards more transparency (and predictability) in the context of offensive cyber operations.

Capacity

Assessing Cyber Spending

Government funding aimed to enhance cybersecurity can be perceived as either heightening or reducing the threat level in this environment, depending on whether the spending is directed toward defensive or offensive measures. In order to clarify this, a distinction is made in the trend table (Table 1) between ‘cyber military spending’, which includes both offensive and defensive capabilities, and ‘national cybersecurity and counter cybercrime spending’, which is purely defensive. Our analysis of open-source documents and budgets shows current government spending in both categories from eight countries (Table 2 and Table 3).[15] Though clear figures on government spending in this domain are extremely difficult to discern, from this analysis it can be deducted that government spending for both cybersecurity and cyber military capabilities is increasing. This claim is evidenced by the sheer lack of budgetary information for cyber capabilities available for the years between 2009 and 2017, compared to the large sums reported in recent years. This trend does not come as a surprise and is emblematic of the cyber domain’s exponential rise in prevalence, which government cyber-related spending is simultaneously a symptom of, and a cause for.

|

Country |

Annual Budget (latest available year) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

United States[16] |

€ 7,028,300,000 |

2019 |

|

United Kingdom[17] |

€ 194,000,000 |

2019[18] |

|

Germany[19] |

€ 135,452,000 |

2019 |

|

Netherlands[20] |

€ 61,000,000 |

2019 |

|

Canada[21] |

€ 67,800,000 |

2019 |

In response to growing awareness of the damage caused by cyberattacks, governments are dedicating more resources to cybersecurity in order to protect their ICT systems (Table 2). The United States remains at the forefront of cybersecurity spending, while countries such as France and the UK have followed suit by dedicating significant amounts of funding towards cybersecurity capabilities. The rise in investment toward defensive measures is also indicated by the creation of dedicated agencies and departments that focus on cybersecurity. Recently created agencies such as the Agency for Innovation in Cybersecurity in Germany highlight that cybersecurity competences are increasingly centralized in specific sectors of the government, and receive separate funding accordingly.

|

Country |

Annual Budget (latest available year) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

United States[22] |

€ 7,150,000,000 |

2019 |

|

United Kingdom[23] |

€ 152,500,000 |

2019[24] |

|

France[25] |

€ 228,600,000 |

2019 |

|

Australia[26] |

€ 518,500,000 |

2019 |

|

Denmark[27] |

€ 312,600,000 |

2019 |

As a reflection of the increase in states disclosing offensive cyber capabilities, cyber military spending is also rising. The US leads this trend, with significant portions of the 2019 annual budget of 7.15 billion euros being allocated to the US Cyber Command.[28] Under both the Obama and Trump administrations, efforts have been undertaken to expand the capabilities of the US Cyber Command, for example through an increase in personnel, a greater operational mandate, and enhanced technical capabilities.[29] Although overall military spending is significantly lower in the other examined countries, their investments into offensive cyber capabilities relative to previous years is indicative of the efforts undertaken by the respective governments to further develop the cyber capabilities of their armed forces.

Activities

Conflicts between states are taking new forms, and cyber operations are playing an increasingly important role. These operations aim to infringe on the availability and integrity of data and ICT systems through what can be described as a Computer Network Attack (CNA).[30] This can be accomplished through denial of service or destructive malware insertion and other means. It often equally requires espionage or intelligence activity – i.e. the ability to violate the confidentiality of data. This precursor, formerly known as Computer Network Exploitation (CNE), includes capabilities known as Intelligence, Cyber Espionage, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and Operational Preparation of the Environment (OPE).[31] Indeed, the capability of states to inflict kinetic-effect harm in cyberspace requires to various extents the ability to conduct intelligence operations. However, the exact nature of these attacks is ubiquitous. While some cyber capabilities are reserved for the battlefield and are at least somewhat defined, other capabilities are less clear.[32] The lack of clarity on exactly what capabilities exist in cyberspace, means that it is very difficult to describe comprehensively what the “means” (delivery systems or weapons) are.

Cyberspace provides states a veil of anonymity to engage in malign cyber activity in order to achieve strategic and operational gains. Across the spectrum of cyberspace we see that states are more openly engaging in cyberattacks against their adversaries, including cyber espionage (a form of CNE), CNA, and disinformation campaigns.[33] While attribution remains difficult to assign, targeted states are increasingly naming and shaming malign actors.[34]

Cyber Espionage

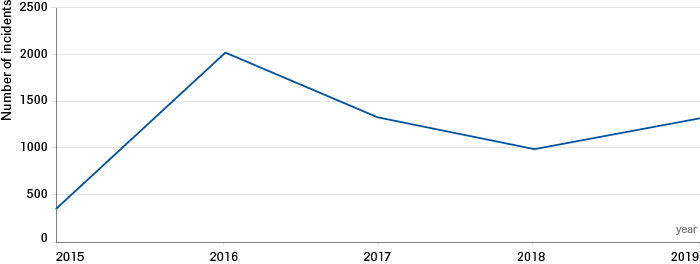

A recent rise in reported cyber espionage can be observed over a ten year period (See Figure 1).[35] Specifically, China has been engaged in intellectual property and advanced military technology theft following a recent short hiatus.[36] The short hiatus can be attributed to US diplomatic efforts, such as the agreement between President Obama and President Xi,[37] the indictments of five People Liberation Army officers and Chinese businessman Su Bin,[38] the threat of sanctions,[39] but also the growing sophistication and re-organization of the Chinese forces.[40] Subsequent to the election of President Trump, and a significant deterioration of the relationship between Washington and Beijing due to rising political and economic tensions, Chinese cyber espionage is again on the rise.[41] This trend reflects recent reports by cybersecurity companies which have registered an increased number of attacks by Chinese hackers against US companies, as well as indictments by the US Justice Department against three Chinese nationals in November 2017.[42]

Source: Council on Foreign Relations “Cyber Operations Tracker”. Cyber Espionage is a form of Computer Network Exploitation (CNE).

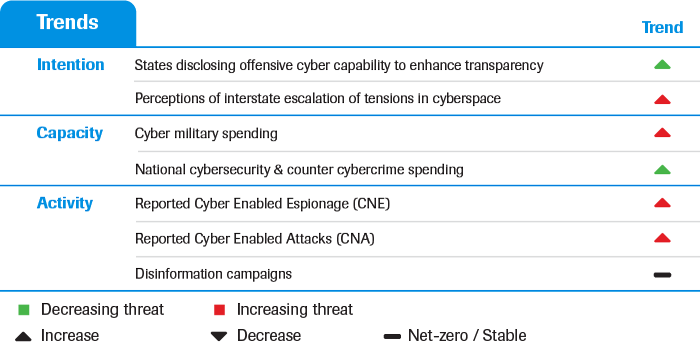

Computer Network Attacks

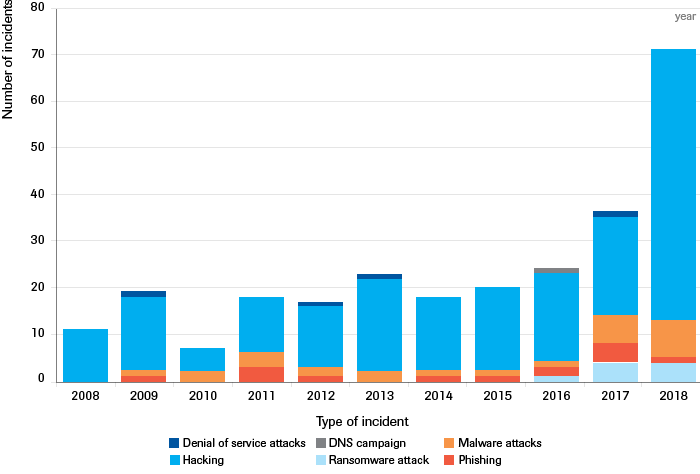

Similarly, Computer Network Attacks (CNA) are increasingly prevalent, as indicated by a rise in significant cyber incidents between 2008 and 2018 (see Figure 2).[43] Denial of service, DNS campaigns, malware attacks, phishing, and ransomware attacks seek to damage, destroy, or disrupt computers and/or computer operations,[44] which directly or indirectly negatively impacts states.[45] Notable CNA attacks include Stuxnet (2010), attacks against the Ukrainian power grid (2015), and WannaCry (2017).[46]

Source: Center for Strategic and Interntional Studies (CSIS) “Significant Cyber Incidents” Category “Hacking” includes all entries that were too general in nature to be classified into one of the other categories.

Disinformation Campaigns

Cyber-enabled disinformation campaigns are likely on the rise, however due to insufficient data for the last decade, a final determination cannot be made on this issue (Figure 3 shows data only for pro-Kremlin disinformation cases over the last four years). Nonetheless, recent reports highlight how states are engaging in comprehensive disinformation campaigns to influence public perception and erode trust in democratic systems.[47] A recent development in this regard is the rise of “Deepfakes”, i.e., hyper-realistic, difficult-to-debunk fake videos, which may have significant impact in shaping public opinion on a respective issue.[48] However, a simultaneous rise in efforts to counter disinformation campaigns is visible among European countries, especially in light of the impact these campaigns can have in times of elections.[49]

International Order in Cyberspace

Setting Rules of the Road

Attempts to regulate these activities in cyberspace have taken place on the intergovernmental level, to varying degrees of success. In 1998, Russia introduced a resolution on information and telecommunications technology in the context of international security to the United Nations General Assembly.[50] This represented the first time that the topic of cybersecurity was to be addressed under the auspices of the United Nations. Since 1998 the UN Secretary-General has submitted regular reports to the General Assembly on the views of Member states on the issue. Various other developments have unfolded within the UN context in the meantime, including a proposal of several states for an international “code of conduct for information security” in 2011.[51] Whilst a majority of the Member states decided that a treaty was not a viable option, they have instead focused on setting out on a path of norm development.

The Application of International Law

* Norms are voluntary, legally non-binding commitments, that reflect a common standard of acceptable and proscribed behaviour, accompanying and expanding on existing legal understanding rather than attempting to craft new law. It is too early to identify long term trends for norm adherence in the field of international security in cyberspace as the norm-setting process in this space is relatively new – 11 norms were introduced by the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts in de Field of information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (GGE) in 2013 and 2015. This pulse therefore depicts norm adoption, the degree to which political norms are embedded in (inter)national policies and regulation, and their impact on the international order.

Whilst it has become a settled principle that international law applies in cyberspace,[52] it is sometimes unclear when and, more specifically, how existing international law is to be interpreted and applied. In 2013 the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts in the field of ICT (GGE), the main vehicle within the UN First Committee that deals with international security and disarmament in cyberspace, declared that international law is “applicable and is essential to maintaining peace and stability and promoting an open, secure, peaceful and accessible ICT environment.”[53] Despite this, recent events have shown a worrying trend whereby state and non-state actors alike are engaging in behavior that threatens the stability of cyberspace, partly due to both the prevalence of legal gray areas, and to the uncertainties stemming from the multistakeholder nature of the domain.

Multilateral Norm-Setting

Establishing finely-delineated legal responsibilities for the various regimes in cyberspace is often not possible. Indeed, legal agreements have proven to be too difficult and time-consuming given the definitional and ideological differences between East and West. Therefore, the 2013 GGE report instead focused on the development of norms[54] - voluntary, legally non-binding commitments that reflect a common standard of acceptable and proscribed behavior, accompanying and expanding on existing legal understandings rather than attempting to craft new law. Further means of promoting common understandings mentioned in the GGE Reports include the application of confidence building measures - technical or practical measures that aim to enhance transparency, communication and trust between actors. Although the GGE Reports of 2013 & 2015 constitute important steps towards multilateral consensus on the issue, the contemporary view is that the divergent views of states are becoming more prominent and the schisms are widening. This was compounded by the fact that the last GGE in 2017 failed to reach consensus in their report, reflecting slow progress in multilateral fora on how international rules should be interpreted in the context of cyberspace. The UN First Committee is now split across two competing processes: an Open-Ended Working Group (Russian proposal) and a GGE (led by the US).[55]

Multilateral Stagnation and Multi-stakeholder Acceleration

The ability of governments to successfully manage the threat of major conflict in cyberspace is not only hampered by the rapid development of digital technologies and the difficulties in attribution, but also the dominant role of non-state actors in all shapes and forms (attacker, victim, media or carrier of attacks), as well as their unclear relationships with the government. Traditionally all questions related to international peace and security occur within the governmental remit of states and the UN First Committee, whilst in reality governments only constitute one of three stakeholder groups in the wider cyberspace ecosystem. It is a domain that is largely run by the private sector, which owns and runs most of its digital and physical assets, and civil society, which is largely responsible for coding and running the global Internet functions. This may lead to ambiguity in the application of international law and appropriate responses. Take for example the situation of a ‘hack-back’ - offensive cyber operations by non-state actors, who often justify their actions in the name of “self-defense,” as states do not have the capacity to adequately protect them against cyber threats.[56] Because of the significant disruptive and damaging effects hack-backs might have, including for third parties, it may trigger complex international legal disputes and escalations. Only recently have several proposals sought to curtail hack-backs - most notably the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) norm against offensive cyber operations by non-state actors,[57] and the Paris Call on Trust and Security in Cyberspace.[58] At the same time, such “active cyber defense” by the private sector would already be unlawful in most states, while in other states it may not be prohibited or may even be reconsidered as a lawful tool.[59]

Failure to reach meaningful progress at the multilateral level has led other stakeholders to take the reins and become more involved in developing rules of the road. This is not the first time that this has occurred - nongovernmental groups have previously helped reshape global discussions on responsible behavior and introduced new norms for unprecedented international problems.[60] In contrast, however, the technological issues involved in governing cyberspace are complex and the rapid pace of change calls for a more collaborative approach than ever before. Private institutions have therefore also become engaged in developing policies that affect the markets and industries over which they preside, sometimes on their own initiative and sometimes in partnership with governments or civil society organizations.[61] Similarly, academia and the technical community have contributed by substantiating policy with more concrete or practical guidelines and solutions.[62] It remains to be seen however just how successful proposals of non-state actors such as these will be in limiting malicious cyber operations, and whether they will achieve the crucial step of convincing state actors to adopt, implement and eventually enforce these rules of the road. Conflicting stances of states on how and when to implement rules, and the current inability to assess acceptance of normative initiatives therefore account for the indicators relating to offensive cyber operations in the table above (Table 4).

Protecting Critical (Internet) Infrastructure

The relative success that norms can have in creating common ground amongst stakeholders is illustrated by the protection of the public core of the Internet. Responses to threats against the core Internet protocols and functions have required the cooperation of states, the private sector and civil society groups, as the Internet is privately-owned and the infrastructure underpinning it governed and maintained by a community made up of individuals and civil society groups.[63] While the idea of protecting the core Internet functions has a longer history, the notion only recently became the subject of various norm proposals, most notably of the GCSC[64] and the Internet Society Mutually Agreed Norms of Routing Security.[65] The proposal of the GCSC has since been accepted and adopted by several institutions, including its inclusion in the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace[66] and its adoption into law through the EU Cybersecurity Act.[67]

Another positive development is the degree to which state and non-state actors are taking measures to protect their critical infrastructure. Critical infrastructure can be defined as “systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.”[68] Recent events concerning national power grids as well as the extent to which automated systems are integrated with each other has led to fears that these systems may be susceptible to Offensive Cyber Operations. Various efforts at the multilateral, regional and national levels have aimed to address the issue of critical infrastructure protection, amongst them the GGE Report of 2015 which repeatedly emphasized the need to protect critical infrastructure and their associated information systems from ICT threats.[69] The United States Executive Order 13800[70] was aimed at improving the nation’s cyber posture and capabilities in the face of intensifying cybersecurity threats, whereas the National Institute of Standards and Technology also issued a report for improving critical infrastructure cybersecurity.[71] The European Union has been undertaking its own efforts in this area,[72] and the OSCE identified critical infrastructure protection as an important issue in its confidence building measures and other decisions.[73]

Civil society groups have extended this debate by focusing on elements of critical infrastructure that require specific attention, such as calling for the protection of the technical infrastructure that supports elections and plebiscites.[74] Nothing reflects genuine political independence more than national participatory processes, such as elections. Whilst the UN Charter sought to grant strong protections against undue external interference, those protective measures have now come to be challenged again in the digital age - voting system instruments and software may be vulnerable to attacks, whilst voter registration data is collected on a vast scale and published online.[75] Elections and participatory processes should be carried out in accordance with national laws, but cyber operations originating from outside a state’s jurisdiction may necessitate a coordinated response. Norms such as these build upon and re-affirm international legal protections already afforded against external interference in the internal affairs of states, whilst calling for a commitment from governments as a modest first step towards effective multilateral cooperation. The relevant success of the norms of the GCSC as well as regional initiatives and national laws are evidence of the general positive trends in awareness and acceptance of norms and rules in cyberspace.

Conclusion: Building Bridges Between Multilateralism and Multistakeholderism

This paper has examined trends relevant to conflict in cyberspace by delving into the intentions, capabilities and activities of states in this critical domain. The primary takeaway is that conflict in cyberspace is intensifying, and is likely to continue to do so. The rise in reported cyber espionage (Figure 1) and Computer Network Attacks (Figure 2), as well as the indication that disinformation campaigns are proliferating, is leading states to regard threats emanating from cyberspace as a crucial security concern, which in turn contributes to an escalation of tensions between states and an increase in cyber military spending (Table 3). However, this dire outlook is at least partially counterbalanced by an increase in resources allocated to national cybersecurity (Table 2), positive developments in the involvement of non-state stakeholders in the norm-setting process, and the increased acceptance of norms and rules in cyberspace (Table 4).

The development of norms in cyberspace have followed conceptual discussions about the rights and responsibilities of actors. The problematic trends highlighted in the first section of this report cannot be solved by states alone, but with all stakeholders working together cooperatively. Due to the shared responsibility in cyberspace between the various regimes, both state and non-state norms can and do overlap. One of the challenges of agreeing on norms of behavior in cyberspace is that norms and CBMs are sometimes formulated by one set of actors but expected to be executed by another. This requires that the actor groups, regimes, and initiatives fully recognize each other’s mandate or legitimacy.

For these initiatives to work, however, the relevant stakeholder groups must come together to ensure that the solutions are as effective as they can be whilst avoiding overlaps, with the primary objective of creating coherence between these initiatives. Whilst the international peace and security field within cybersecurity is moving towards acceptance and adoption of norms, there remains a greater need to take stock of the various initiatives, push for implementation and enforcement or follow up on compliance. Attitudes change and so do understandings and acceptance towards certain types of behavior, though usually this happens over an extended period of time. For the status quo to move from norm development to adoption and adherence, stakeholders need to stand behind the norms which they feel are important both in words and in actions. Only once viable pathways for carrying those norms forward are identified will it become possible to assess norm adherence.

Appendix A: States’ First Disclosure of Offensive Cyber Capabilities (non-exhaustive)

|

Actor |

Document |

Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

|

United States November 2006 |

“Operations in cyberspace are a critical aspect of our military operations around the globe. The enclosed NMS-CO is the product of significant reflection and debate within our military and government. It describes the cyberspace domain, articulates threats and vulnerabilities in cyberspace, and provides a strategic framework for action. The NMS-CO is the US Armed Forces' comprehensive strategic approach for using cyberspace operations to assure US military strategic superiority in the domain. The integration of offensive and defensive cyberspace operations, coupled with the skill and knowledge of our people, is fundamental to this approach.” (p. vii) |

|

|

United States February 2013 |

“The successful execution of CO requires the integrated and synchronized employment of offensive, defensive, and DODIN operations, underpinned by effective and timely operational preparation of the environment. CO missions are categorized as offensive cyberspace operations (OCO), defensive cyberspace operations (DCO), and DODIN based on their intent.” (p. vii) |

|

|

France June 2008 |

“En outre, dans la mesure où le cyberespace est devenu un nouveau champ d’action dans lequel se déroulent déjà des opérations militaires, la France devra développer une capacité de lutte dans cet espace. Des règles d’engagement appropriées, tenant compte des considérations juridiques liées à ce nouveau milieu, devront être élaborées.” (p. 53)

[Translation: In addition, as cyberspace has become a new field of action in which military operations are already taking place, France will have to develop a fighting capacity in this area. Appropriate rules of engagement, taking into account legal considerations related to this new environment, will need to be developed.] |

|

|

United Kingdom June 2009 |

“There is an ongoing and broad debate regarding what ‘cyber warfare’ might entail, but it is a point of consensus that with a growing dependence upon cyber space, the defence and exploitation of information systems are increasingly important issues for national security. We recognise the need to develop military and civil capabilities, both nationally and with allies, to ensure we can defend against attack, and take steps against adversaries where necessary.” (p. 14)

“Exploiting opportunities in cyber space covers the full range of possible actions that the UK might need to take in cyber space in order to support cyber security and wider national security policy aims; for example, in countering terrorism and in combating serious organised crime.” (p. 15) |

|

|

Japan May 2010 |

Information Security Strategy for Protecting the Nation 2010 |

“In order to reinforce the measures against malware infections, maintain and improve counteractive capabilities against information security incidents and strengthen the information security measures taken by individuals on their PCs by promoting security awareness.” (p. 13)

“Reinforcement of policies taking account of possible outbreaks of cyber attacks and establishment of a counteractive organization To protect the nation from any cyber attacks that may risk the national security and prompt crisis management, the general mode of readiness must be reinforced and an organization to efficiently counteract any such cyber attacks must be established.” (p. 2) |

|

Switzerland June 2012 |

National strategy for Switzerland’s protection against cyber risks |

“Crisis Management – Active measures to identify the perpetrator and possible impairment of its infrastructure in the event of a specific threat.” (p. 4)

“As a matter of fact, there can be no absolute protection against cyber attacks, hence a functioning collaboration of reactive and preventive capabilities are pivotal in order to minimise risks, limit damage and re-establish the initial state of operation of an attacked system.” (p. 10) |

|

India 2013 |

“In the battlefield milieu, information, its integration and conversion into real-time actionable intelligence shall provide the battle winning edge to a Commander. We also need to exploit the electromagnetic spectrum to safeguard own combat systems, intercept and decipher the adversary’s information systems in a time bound manner. In addition, we must have the capability to prevent an attack or contain it and affect swift recovery, while at the same time have the ability to target adversary’s critical infrastructure and military capabilities. 9. The strategic forces need to be facilitated/ supported by real-time information. These will include satellites that produce sub metric resolution and backed up by UAVs with great staying power in the area of interest.” |

|

|

Brazil November 2014 |

“Defesa Cibernética - conjunto de ações ofensivas, defensivas e exploratórias, realizadas no Espaço Cibernético, no contexto de um planejamento nacional de nível estratégico, coordenado e integrado pelo Ministério da Defesa, com as finalidades de proteger os sistemas de informação de interesse da Defesa Nacional, obter dados para a produção de conhecimento de Inteligência e comprometer os sistemas de informação do oponente.” (p. 18)“Possibilidades da Defesa Cibernética 2.5.1 São possibilidades da Defesa Cibernética: a) atuar no Espaço Cibernético, por meio de ações ofensivas, defensivas e exploratórias” (p. 21)

[Translation: “Cyber Defense - a set of offensive, defensive and exploratory actions carried out in the Cyber Space, in the context of a national level strategic planning, coordinated and integrated by the Ministry of Defense, with the purpose of protecting information systems of interest to National Defense, obtain data for the production of Intelligence knowledge and compromise the information systems of the opponent. They are possibilities of the Cyber Defense: a) to act in the Cyberspace, by means of offensive, defensive and exploratory actions;” |

|

|

Poland January 2015 |

- operational and support subsystems - capable of independently running defensive (protective and defense) and offensive cyber operations, as well as providing and receiving support as part of allied operations. (Point 7, p. 9) |

|

|

Netherlands February 2015

Previous: National Cyber Security Strategy (NCSS) 2011, no mention of offensive capabilities |

Defensie Cyber Strategie, Brief van de Minister van Defensie |

Door de komende jaren actief aan deze speerpunten te werken, wil Defensie de verdere versterking van haar digitale middelen maximaal ondersteunen. De speerpunten voor de verdere versterking van de digitale middelen van Defensie betreffen: 5. de digitale weerbaarheid van Defensie; 6. het inlichtingenvermogen van Defensie in het digitale domein; 7. de ontwikkeling en de inzet van cybercapaciteiten als integraal onderdeel van het militaire optreden (defensief, offensief en inlichtingen). (p. 3)

[Translation: “By actively working on these spearheads in the coming years, the Ministry of Defense wants to provide maximum support for the further strengthening of its digital resources. The spearheads for the further strengthening of Defense's digital resources are: 5. the digital resilience of Defense; 6. the intelligence capacity of Defense in the digital domain; 7. the development and deployment of cyber capabilities as an integral part of military action (defensive, offensive and intelligence).”] |

|

Israel August 2015 |

Israel Defense Force (IDF) Strategy (Unofficial English translation by the Harvard Belfer Center) |

“Cyberspace is another area of combat. Defense, intelligence collection, and assault activities will be carried out in this space. Building the IDF’s force in this sphere will be based on these actions: A. Establish a cyber arm that will constitute the main HQ subordinate to the Chief of the General Staff to operate and build the IDF’s cyber capabilities and will be responsible for planning and implementing combat in cyberspace.” |

|

Australia April 2016 |

“Australia’s defensive and offensive cyber capabilities enable us to deter and respond to the threat of cyber attack.” (p. 28) |

|

|

Germany November 2016 |

National Cyber Security Strategy Germany 2016

Previous: 2011 Cyber Security Strategy, no mention of offensive capabilities |

“Cyber-Verteidigung umfasst die in der Bundeswehr im Rahmen ihres verfassungsmäßigen Auftrages und dem völkerrechtlichen Rahmen vor- handenen defensiven und offensiven Fähigkeiten zum Wirken im Cyber-Raum” (p. 46)

[Translation: “Cyber-Defense includes the defensive and offensive abilities to work in cyberspace in the Bundeswehr within the framework of its constitutional mandate and international legal framework"] |

|

United Kingdom November 2016 |

National Cyber Security Strategy 2016 - 2021

Previous: 2011 Cyber Security Strategy, no mention of offensive cyber capabilities |

"We will have the means to respond to cyber attacks in the same way as we respond to any other attack, using whichever capability is most appropriate, including an offensive cyber capability.” (p. 10)

“Offensive cyber capabilities involve deliberate intrusions into opponents’ systems or networks, with the intention of causing damage, disruption or destruction. Offensive cyber forms part of the full spectrum of capabilities we will develop to deter adversaries and to deny them opportunities to attack us, in both cyberspace and the physical sphere. Through our National Offensive Cyber Programme (NOCP), we have a dedicated capability to act in cyberspace and we will commit the resources to develop and improve this capability.” (p. 65) |

|

China December 2016 |

二、目标 以总体国家安全观为指导,贯彻落实创新、协调、绿色、开放、共享的发展理念,增强风险意识和危机意识,统筹国内国际两个大局,统筹发展安全两件大事,积极防御、有效应对,推进网络空间和平、安全、开放、合作、有序,维护国家主权、安全、发展利益,实现建设网络强国的战略目标。

[Translation: “Guided by the overall national security concept, we will implement the development concept of innovation, coordination, green, openness, and sharing, enhance risk awareness and crisis awareness, coordinate the two major domestic and international situations, and coordinate the development of two major events, actively defending and responding effectively.”] |

|

|

Canada 2017 |

Strong, Secure, Engaged - Canada’s Defence Policy

Previous: 2010 Cyber Security Strategy Strategy, no mention of offensive capabilities |

“To better leverage cyber capabilities in support of military operations, the Defence team will: - Develop active cyber capabilities and employ them against potential adversaries in support of government-authorized military missions.” (Initiative 88, p.73) |

|

South Africa March 2017 |

“During the FY2016/17 the DOD has developed a comprehensive departmental Cyber Warfare Strategy aligned with the national policy regarding South Africa’s posture and capabilities related to offensive information warfare actions.” (p. 6-7) |

|

|

Switzerland November 2017

Previous: |

“Chaque opérateur d'infras-tructure critique est respon-sable de sa défense. Le SRC (Service de renseignement de la Confédération) peut prêter assistance en cas de cyberattaque (au besoin avec des contre-mesures offensives). Si les conditions sont remplies, l'armée peut (subsidiairement) l’appuyer.” (p. 8)

“Le DDPS est responsable de sa propre défense (au besoin avec des contre-mesures offensives).” (p. 8)

[Translation: "Each critical infrastructure operator is responsible for his defense. The SRC (Confederation Intelligence Service) can provide assistance in case of cyber attack (if necessary with offensive countermeasures). If the conditions are met, the army may (in the alternative) support it.”

The DDPS is responsible for its own defense (if necessary with offensive countermeasures).] |

|

|

New Zealand July 2018 |

“To maintain relevant combat capabilities, including interoperability with close partners, into the future the Defense Force needs to be able to conduct a broader range of cyber operations. This would provide military commanders with a broader set of tools to achieve military objectives and respond to activities that threaten both New Zealand security and the safety of Defense Force personnel.” |

|

|

Sweden May 2019 |

“Sweden is one of the most digitised countries in the world. The Defence Commission concludes that Sweden has to take proper precautions in the information and cyber security field and develop the capability to act defensively and offensively in the cyber domain. The Defence Commission takes the view that the Swedish Armed Forces should be tasked to contribute to the comprehensive cyber defence in the total defence. Beyond protecting their own systems, the Swedish Armed Forces will be responsible for offensive cyber defence capabilities in the total defence.” (p. 7) |

|

|

Denmark Published February 2019, stated 1/7/2018 |

“Denmark has since 2016 contributed to NATO’s cyber defence and in 2018 it was announced that Denmark can also contribute to NATO operations with effects from the offensive cyber capability. Employment of offensive cyber capabilities in a military operation will take place under the command of the Chief of Defence.” (p. 1) |

|

|

Malaysia 2010 |

“The development of a cyber-warfare capability is an important step towards counterbalancing the ability of other countries in the region and to defend important national targets from all forms of threats. It is important to stop any form of encroachment into national defence’s computer systems and networks. Concurrently, it also provides the room for developing offensive capabilities for conducting cyber- operations when necessary.” (p. 13) |

Appendix B: Timeline of Major Cyber Incidents 2009-2019

Notes

This report used only publicly available sources and data, preventing it from giving absolute numbers and findings. Determining cybersecurity spending is challenging because: (i) of the lack of consistent reporting; (ii) the absence of a unified definitions, which makes it difficult to delineate which costs are specifically attributed to cybersecurity per se; (iii) cybersecurity is increasingly evolving into the integral part of government operations – rather than being a separate unit costs; (iv) collecting and mapping the data of ICT and cybersecurity investments is generally complicated as cybersecurity is mostly approached qualitatively, and not primarily from a cost perspective.

This is all spending on the National Cyber Security Programme, minus 44%. This 44% was spent on ‘deter’ during the 2016-2019 period (as opposed to ‘defend’, ‘develop’ and ‘international’, see page 29 of the abovementioned document). Arguably, the spending under the ‘deter’ header can be considered military expenses. Roughly 42% of the total budget was used for the creation of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) which operates under GCHQ.This figure was then converted to euro using the average exchange rate for 2019 and rounded to the nearest 100,000. National Audit Office, “Progress of the 2016–2021 National Cyber Security Programme,” March 15, 2019, 22, link.

Offensive cyber operations by non-state actors - or active cyber defense as it has more commonly become known - should be understood as a set of measures ranging from self defense on the victim’s network to destructive activity on the attacker’s network. Offensive operations within this continuum imply for the defender to act out-side of its own network independently of its intention (offense or defense) and the legal qualification of its acts. For a discussion on offensive cyber operations, including the contextual and legal reasoning behind the capacity of States to take measures to protect non-State actors, see the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace Norm Against Offensive Cyber Operations by Non-State Actors and Additional Note to the Norm link.

Guidelines and best practices can help develop a culture of security. National policies on information and network security are based on a multidisciplinary and multistakeholder approach. A culture of security cannot arise just out of technical solutions - a comprehensive approach is needed that addresses socio-economic and legal considerations, and governments must therefore interact and engage with private and civil society actors. See Working Party on Information Security and Privacy, “The Promotion of a Culture of Security for Information Systems and Networks in OECD Countries” (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, December 16, 2005), 7, link.

A number of states openly insist that states should play a key role in governing Internet policy and the Internet’s critical resources. Other states believe that efforts should be made to maintain what is generally referred to as the “multi-stakeholder model” of Internet governance, defined often as “a form of participatory and diverse form of governance”, and try to keep discussions on Internet governance separate from discussions on international peace and security. See United Nations, “Cyberspace and International Peace and Security - Responding to Complexity in the 21st Century” (United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), 2017), link.